The centring of the margins occurs in the space between worlds. Things are flipped upside down. A prince throws open the gates, a jester wears the crown.

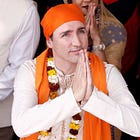

In 2013, Justin Trudeau assumed leadership of the Liberal Party in a similar fashion to his father Pierre, Prime Minister from 1968–1979 and 1980–1984. As Pierre rode the late 1960s wave of enthusiasm for new ways of thinking, Justin would also harness young people and their eagerness for change.

Justin made a point to embrace, celebrate, and prioritize the marginalized. In the 2015 federal election campaign, one of Justin’s key pledges was to “appoint an equal number of men and women to cabinet, and adopt a government-wide appointment policy to ensure gender parity and greater representation of aboriginal people and other minorities.”1

In the 2015 federal election, Justin led the Liberals to victory and gained 148 seats in parliament—the largest single-election seat increase in history. Outgoing Prime Minister Stephen Harper resigned as leader of the Conservative Party afterwards.

Under Harper from 2006-2015, Canadians already took great pride in embracing and integrating marginal cultures and peoples. Especially when comparing ourselves to the United States, we were not afraid to boast about our enlightened ‘cultural mosaic’ versus their adversarial ‘melting pot’.

Throughout Canada during this time, even the word ‘immigrant’ disappeared from popular usage, with ‘newcomers’ and ‘new Canadians’ substituted in its place.

After his win in 2015, Justin was no longer only the heir to Pierre Trudeau, but also his father's ideas of multiculturalism and Canadian identity. But, it soon became clear that Justin didn’t inherit his dad’s intellectual curiosity, verbal wit, dispassionate political philosophy, or couth in enacting reform. In Justin’s defense, it was more important to many that he shared his father’s name.

And Justin certainly understood the spirit of the times. He recognized that ‘progress’ and change were held by many to be moral goods worthy of being pursued for their own sake. When asked about the importance of having a ‘gender-balanced’ cabinet, Trudeau didn’t offer any explanation other than, ‘because it’s 2015’:

Shortly after taking office, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told New York Times Magazine, “there is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada,” [and that] “makes us the first post-national state.”2 Justin embarked on a journey to cement this vision he inherited from his dad.

The guiding principle of Canadian leadership for the past decade could be called centring the margins—doing away with what remains of a shared past, prioritizing change in all things, and venerating the outsider. The most visible and far-reaching example of this attitude can be seen through immigration policy.

At the turn of the 20th century, Canada was likened to a bustling railway station; a liminal space for travelers on their journey, who often continued on to the greener pastures of the United States. Canada today could be described along these lines as an overcrowded airport.

Many Canadian cities and towns have been rapidly transformed by unprecedented mass immigration. As a result, Canada’s once unquestioned, positive consensus on immigration and ‘new Canadians’ has begun to unravel.3

In true Canadian fashion, we’ve mostly managed this transformation in a boring way—almost entirely legally, calmly, and without many comfortable even noticing. The lack of reaction to these changes until very recently, may be explained by Canada’s position on the periphery of great empires and bigger nations. Like the provincials of the ancient world, we often attempt to ‘impress the capital’, by embracing change.

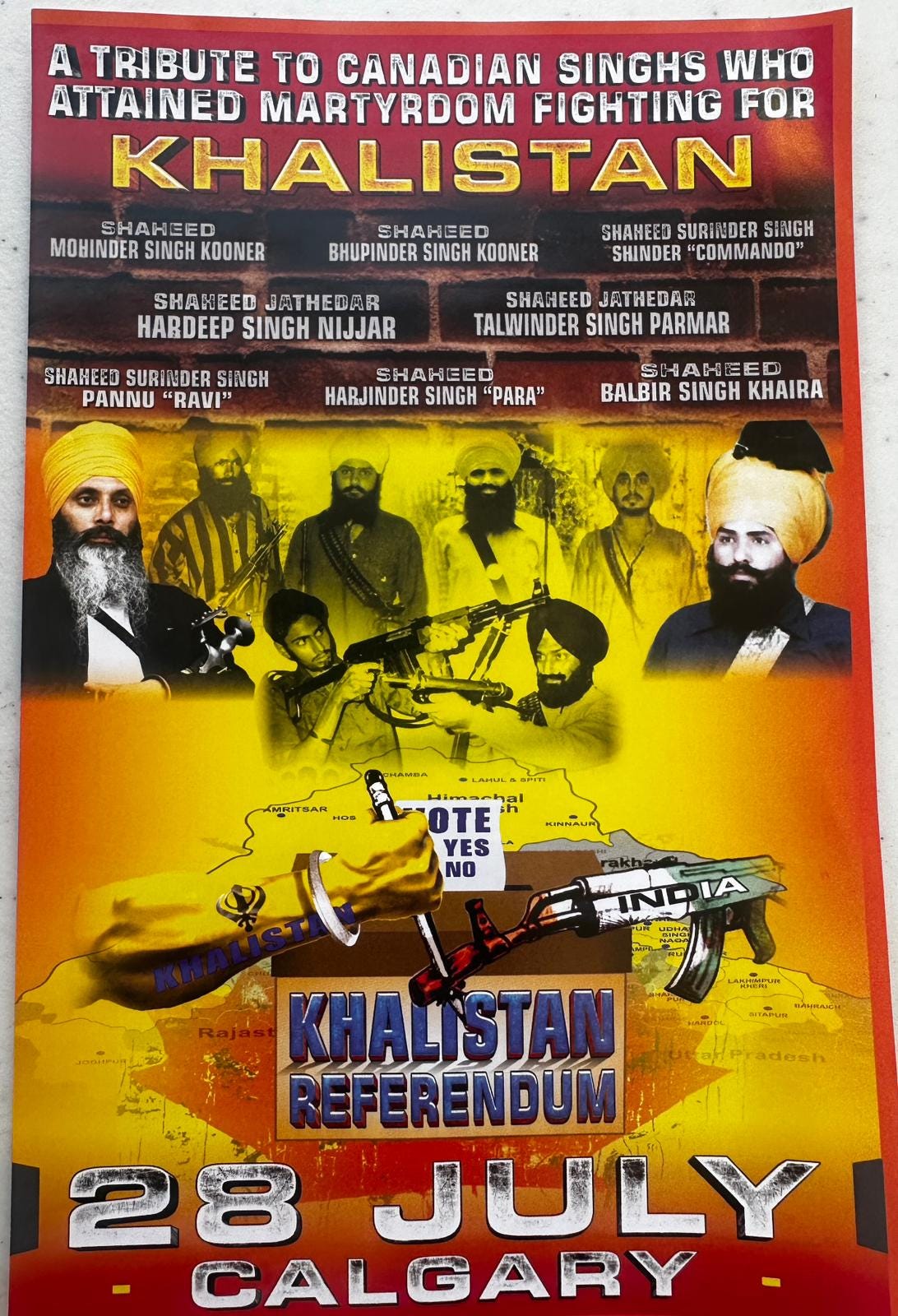

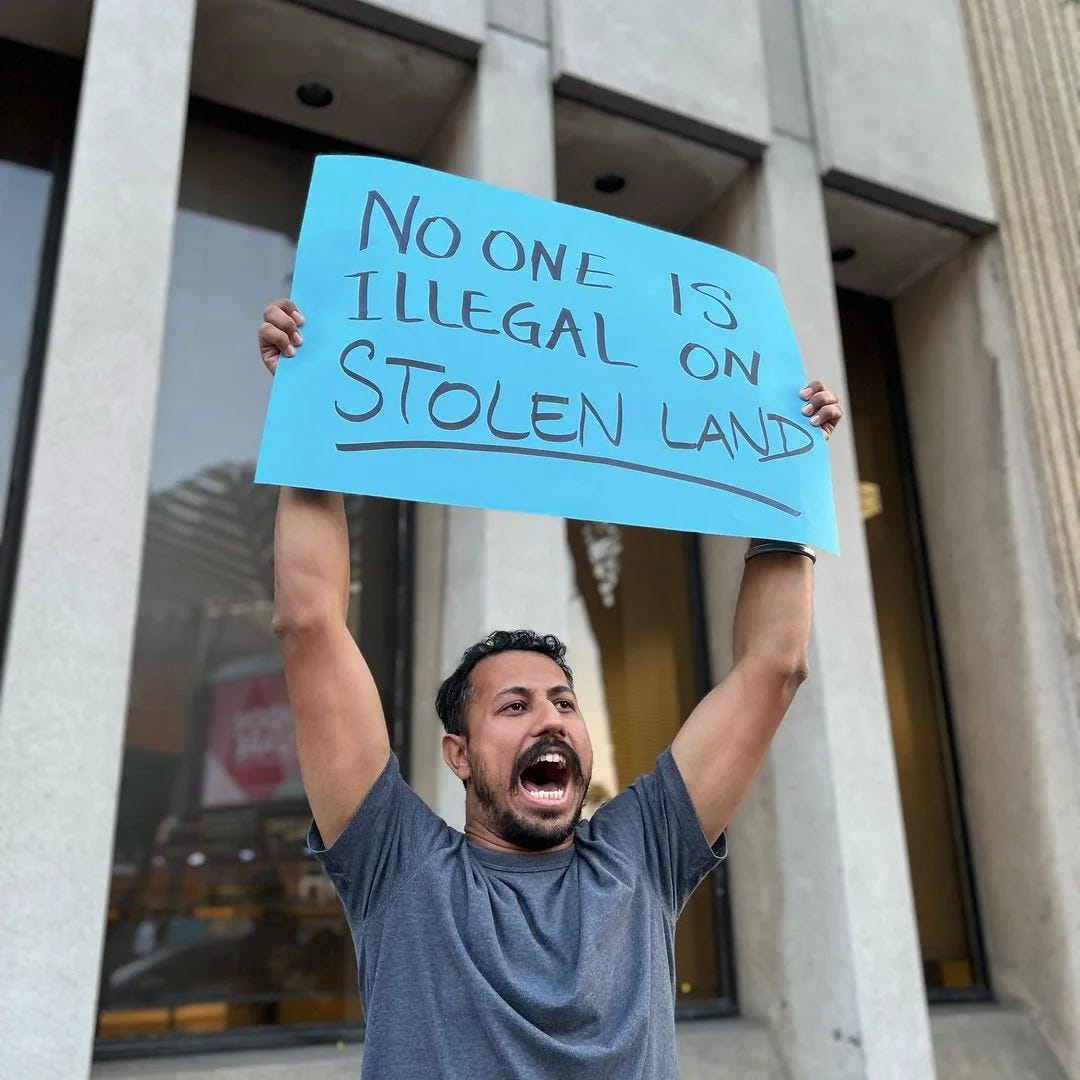

But problems are arising from centring the margins. Canada’s urban centres often serve as microcosmic battlegrounds for ethnic, political, and religious conflicts from around the world.

The often used justification for this state of affairs—a sort of karmic justice for the crimes of colonialism—reveals the easy exploitability of the project enacted by Canada’s leaders. Canada’s deferential and welcoming approach to the outsider is often interpreted as weakness, and met with resentment and entitlement.

Much of the reaction against the established order of Canada today has been targeted at Justin Trudeau. He’s been on the receiving end of more vitriol from the public than perhaps any other Prime Minister—even surpassing his father. An overwhelming majority of Canadians have recently called for Justin to resign.4

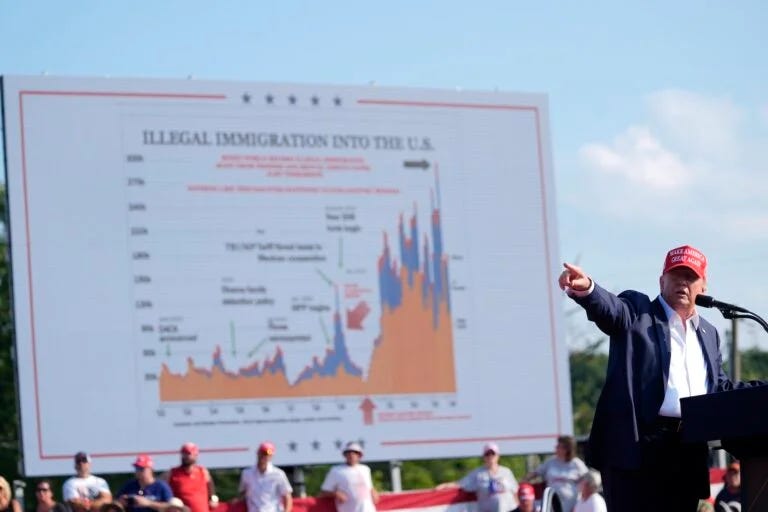

Things have gotten to the point where even our neighbours to the south are actually paying some attention to us. The most famous and polarizing man alive today, and soon to be once again the ‘leader of the free world’, currently has Canada and Justin in his sights.

But we aren’t that special in drawing President-elect Trump’s attention. Beyond flippantly referring to annexing Canada, Trump has also recently thrown out the possibilities of the United States re-taking control over the Panama Canal, and obtaining the Danish territory of Greenland.5

Many Canadians have had great difficulty understanding the Donald Trump phenomenon. An obnoxious New York billionaire is an unlikely candidate to become the most popular political figure in America. But, Trump initially gathered attention upon himself in a similar fashion to Justin—through focusing on the margins.

Of course, there are differing opinions about who exactly the marginalized are according to Trudeau and Trump.

In 2016, Trump sold himself as a voice for those who felt maligned and powerless—much like Justin did the year prior in Canada. Trump often refers to his supporters as the ‘forgotten men and women of our country’. These people clearly feel pushed to the margins enough to turn to an unapologetic, political outsider who embraced them and their concerns.

As of late, Trump has roused both Americans and Canadians to drum up positive affirmations of patriotism and national pride. He’s struck at Canada by saying we’d be better off simply becoming the 51st state, and referring to the Prime Minister as ‘Governor Trudeau’.

In response, sudden calls in Canada to unite against the Americans ring hollow for many, after being repeatedly told we are a ‘post-national’ society. Patriotic gestures seem especially out of place coming from members of parliament, who unanimously affirmed a few years ago that they are representatives of a genocidal state.6

In tying ourselves to centring the margins in all things, Canadians have largely done away with any consensus about our identity—beyond the need for our own continued negation. This has led growing numbers of Canadians to ask, ‘what exactly is keeping us from just becoming Americans?’

These sorts of questions aren’t all that new—but they were easier to answer in the past. Canada’s in-between symbolism produces a consistent identity crisis of sorts—with talks of separation and annexation always on the table in one way or another.

One could make a pessimistic argument that we never actually became a sovereign nation. And that Canada today is not so different from any period of our past: remaining a continent-spanning company town or economic zone; ruled by a small, wealthy political and business elite beholden to imperial masters; an economy based on resource extraction, land speculation, and ‘coolie’ labour; and a culture and politics which largely ignores our own affairs—preferring the goings-on in the homeland, or the capital of the empire.

On the other hand, we can point to Quebec as an outlier, where a sense of nationhood and distinct character has remained. However, efforts in Quebec to express or codify this sovereignty through political means have often failed.

Protecting the French language and maintaining a secular state have not been sufficient causes to trigger a separation of Quebec to go on their own. In a similar fashion to multiculturalism, Quebec nationalism often ultimately struggles to inspire—relying on a continued negation of what was rather than a positive vision for the future.

Canada has a small part to play in the larger story playing across the Western world. Questions of identity have taken on great importance in recent years—and not just in Canada. Consider the task of assembling a ‘gender-balanced’ cabinet in 2025 vs 2015 to put some of this change in perspective.

In some ways it seems not much has changed in the Trudeau and Trump era. Both men rose to prominence and stayed in positions of influence by taking on the appearances of the margins—riding reversals of hierarchy which accompany transitory periods. Trudeau and Trump may appear to be total opposites, but they represent and occupy this same symbolic space.

Acknowledging the absurdity of Canada’s current situation may be a good first step in moving forward out of this cyclical period—regardless of fantasies of annexation or separation, or the immediate political future of ‘Governor Trudeau’.

In 2025, the visas of 4.9 million people in Canada will expire, and they will be expected to leave the country voluntarily.7 An ideal resolution of this situation would see Canada rapidly lose over ten percent of our population. And there appears to have been little thought put into what will happen if significant amounts of these people decide they’d rather not return home.

At least compared to the Americans, Canadians currently lack the will or stomach to properly address issues like these, as they threaten to spiral out of control. And we are certainly not alone in having to deal with these sorts of problems.

Liberal democracies as a whole are in a liminal state. Ideas held across the Western world regarding nationhood, citizenship, and proper roles of the centre and the margins, are continually being challenged.

It’s possible that Canada has simply sped up some of the inherent contradictions of the age quicker than other countries: as the residual Christian virtues which have inspired our thinking towards concepts like multiculturalism and post-nationalism, are looking for their proper expressions.

We can expect to see continued focus on the borders between peoples, nations, and identities, as we attempt to solve these issues. In Canada, our marginal position in relation to the U.S. will give us front-row seats to see how to move forward—for better or worse.

Entering a new year, with new leaders, Canadians and Americans should prepare once again to focus on the margins, and embrace change—because it’s 2015 2025.

This is an abridged version of an article on Canadian multiculturalism and immigration, found here:

“Trudeau unveils plan to ‘restore democracy’”. The Canadian Press, June 16, 2015

“Trudeau’s Canada, Again.” New York Times Magazine, December 8, 2015.

One poll in August 2024 found 65% of Canadians believe the current federal immigration plan will admit too many immigrants, with 72% believing that Canada’s immigration policy is ‘too generous’.

Leger Marketing Inc. “CANADIAN POLITICS: Immigration and the Temporary Foreign Workers Program”. August 26, 2024.

‘Should Trudeau resign? 69 per cent of Canadians say yes, according to new poll’. National Post, Tristin Hopper, December 24, 2024.

‘Trump is teasing US expansion into Panama, Greenland and Canada’. CNN, December 23, 2024.

‘Feds expect 4.9 million with expiring visas to 'voluntarily' leave Canada in next year’. Toronto Sun, Nov 26, 2024.