The Ancient Worldview

This series has covered the process of Canada becoming ‘multicultural’.

These posts have been inspired by the work of Matthieu Pageau, Jonathan Pageau, Richard Rohlin, and others. This includes Matthieu’s book, The Language of Creation, Jonathan’s YouTube channel and website The Symbolic World, and Jonathan’s conversations with Richard and others regarding Universal History.

Their work often focuses on the worldview of ancient peoples. The ancient worldview sees Man as the mediator between heaven and earth. This worldview is less concerned with materialism and facts derived through the scientific method, and is more focused on human consciousness and experience.

Universal History is a framework to interpret our past. It shows the shared narrative structure, laws, and traditions, that various peoples have used to understand themselves. In particular, this history can help us see how peoples and cultures came into contact with the Christian world—making their place within it.

We’ve entered into this worldview to better understand Canada’s history, and how and why we became ‘multicultural’. We have put forth that Canada has a hybrid symbolism—as a peripheral and liminal state—between worlds, peoples, cultures, and empires.

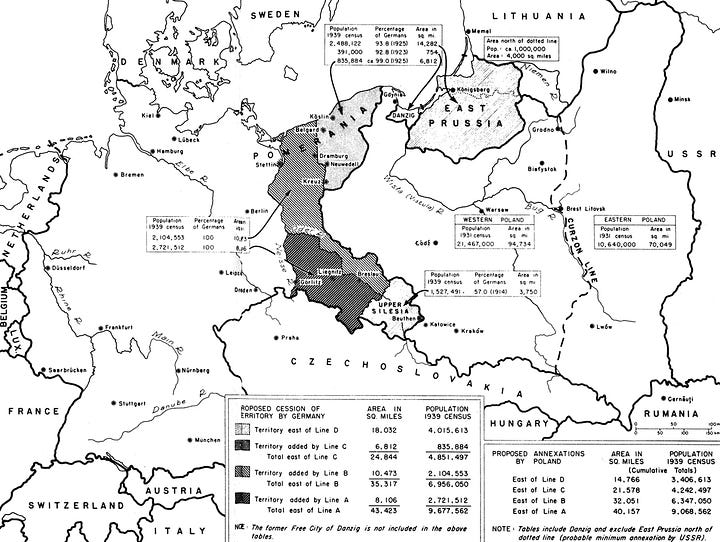

There are several peoples and nations which share this same symbolism: such as those on the borders of empires or bigger nations—like Poland, Wales, or Ukraine, peoples on the limits of ‘known world’—including Ethiopia and Ireland in ancient times, or New Zealand and Australia in the modern era, and countries with a mix of ethnic and language groups—from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Singapore, or Brazil.

The ancient worldview is centred around religious and cultural traditions and stories. Which have endured because they include fundamental and simple truths about our world, and how we experience it. But these truths are difficult to see today. We can’t easily read ancient stories with the same eyes as those who wrote them.

One way of reading the Bible in an ancient or pre-modern way is: as a series of descriptions of the basic patterns of reality, expressed through the imperfect behaviour of Man. Which then culminates with the author Himself entering the story, and showing Man the ideal to follow.

If each story in the Bible carries with it a pattern or description of reality, then when we see similar events in history, it is not coincidence. Rather, it’s a consequence of those original stories containing the building blocks of reality itself. This works in the same way that a finished building must necessarily contain within it its own blueprints.

The Book of Ecclesiastes illustrates the difficulty in grasping the idea that history follows these patterns:

9 The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.

10 Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us.

11 There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after.1

From what we are referring to as this ancient, pre-modern or symbolic perspective, we distinguish between two different types of change, as characterized by writer Matthieu Pageau:

formation is a process by which an identity produces “more of itself and less of the other” by integrating matter. Like the growth of a tree, this process begins with a singular identity (seed) that expands into a coherent structure. This is not change in the ancient sense of transformation, a process that creates “less of itself and more of the other”. Simply stated, change means turning something into something else, whereas formation means producing a greater version of something.2

Along with formation and transformation, we also use the terms margins and centre.

The notion of the centre is that which is orderly, authoritative, safe, clearly defined, orthodox, traditional, or static. The margins are that which is chaotic, leftover, concealed, strange, dangerous, enticing, or foreign.

There are numerous examples in literature of these concepts. J.R.R. Tolkien demonstrates the dual nature of the margins in The Lord of the Rings. The margins of Tolkien’s world are both the Shire; the remote and preserved gardens of the hobbits, and Mordor; where the orcs and the forces of destruction dwell.3

The centre can be more difficult to see, and especially when its been muddied or corrupted. In The Lord of the Rings, Aragorn, the rightful heir to the throne—the living embodiment of the centre—takes on the appearances of the margins. Aragorn disguises himself, and first appears to be dangerous. But he acts as a secret king, and earns his inheritance through his deeds, and eventually ushers in a renewal of the kingdom.

Coming back to Canadian multiculturalism, we will now see how it maps onto some ancient stories and terms.

The most charitable view of the multicultural project in Canada is that it promised to integrate increasingly marginal and foreign religions, cultures, and peoples under one banner—to incorporate and absorb multiplicity—with the aim of renewing and expanding Canada itself.

We saw this at the turn of the 20th century, with the integration of marginal immigrant groups to populate the prairie provinces.

In the 1960s and 70s, we were faced with the possibility of the two Canada’s splitting up. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau instituted multiculturalism to renew the nation’s identity again, and helped prevent Quebec leaving Canada.

Since then, multiculturalism and immigration have been thought of as unquestionable goods—to be used for the renewal and expansion of our identity. But each time this renewal has been attempted, it has been done with ever expanding margins being integrated into a weakened and shrinking centre of traditional Canadian society.

The margins have become centred in the Canada of today. Multiculturalism and immigration have gone hand in hand to produce transformation, in which Canada has become “less of itself and more of the other.”

There are similarities between the techniques and rationale behind multiculturalism, and the building of the Tower of Babel. The Biblical story in which humanity attempts to build a tower capable of reaching heaven.

Babel and multiculturalism are reformation projects—designed to provide certainty, and to hold off the ‘flood waters’ or chaos of the past. Both involve technological planning, sacrificing and mixing of identity, and reaching past traditional limits between peoples. Both also involve efforts to capture and control the processes of renewal.

This ‘Babel pattern’ has produced a powerful focal point in Canada—a tower—that we call multiculturalism, which all attention and energies are directed, in order for us to ‘reach heaven’.

Turning Point, 2015

In September 2015, newspapers and social media networks were flooded with the image of a dead toddler washed ashore in the Mediterranean Sea—the in-between waters of the European, African, and Middle Eastern worlds.

The child’s name was Alan Kurdi. Kurdi was a three-year-old Syrian boy. Kurdi drowned off the coast of Turkey, as his family attempted to reach Europe with the help of smugglers during the 2015 European migrant crisis.

A German newspaper asked the father of the boy, Abdullah Kurdi, where they were headed and who he felt was responsible for his son’s death:

“I wanted to move (to Canada) with my family and with my brother who is currently in Germany,” Kurdi told Die Welt in a telephone interview. “But they denied us permission and I don't know why.” When Die Welt asked Kurdi whether he blamed anyone for the tragedy, he responded: “Yes, the authorities in Canada, which rejected my application for asylum, even though there were five families who were willing to support us financially.”4

However, CBC News reported that Abdullah’s sister, Tima, who lived in British Columbia at the time, had not actually submitted a refugee asylum claim on the family’s behalf.5 But these details had a difficult time catching up to the story.

Internationally, Canada bared responsibility for one of the most sensational tragedies in years. And it just so happened, at this time, Canadians had a chance to re-establish our commitment to prioritizing the margins.

The Kurdi story broke a month before the 2015 federal election. In 2015, the Liberals appeared as a fresh alternative to the stale, status quo Conservatives, who had been in government since 2006. The Liberals were led by a new but familiar face, Justin Trudeau. The eldest son of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Justin certainly had large shoes to fill.

Justin assumed leadership of the party in a similar fashion to his father. As Pierre rode the late 1960s enthusiasm for new ways of thinking, Justin would harness young people and their eagerness for change.

Justin made a point to embrace, celebrate, and prioritize the margins. In making his case during the 2015 election campaign, Justin included plans to “appoint an equal number of men and women to cabinet and adopt a government-wide appointment policy to ensure gender parity and greater representation of aboriginal people and other minorities.”6 Justin also pledged to bring in 25,000 Syrian refugees by the year’s end should his party take office.

In the 2015 federal election, the Liberals gained 148 seats—the largest numerical increase in history. The Liberals totaled 184 seats, while the Conservatives were reduced from 159 to 99, and the New Democrats losing major ground as well, being reduced from 95 to 44.

Stephen Harper resigned as Conservative leader following the election. With his exit, he left Canada more committed to multiculturalism than he found it.

As Prime Minister, Stephen Harper pursued a great deal of change in pursuit of economic renewal. But he also genuinely bought into the ideas passed down by his predecessors—which saw it necessary to support Canada’s multicultural identity through immigration. Harper expanded immigration7 in a mostly economically viable way, and made significant steps towards transforming Canada, making it “less of itself and more of the other”.

Under Harper, Canada’s population identified by the census as ‘visible minorities’—increased from 16.2% in 2006, to 22.3% in 2016. The 2016 census also reported 21.9% of Canadians as foreign-born—nearly matching the record of 22.3% in 1921 during efforts to populate the prairie provinces.

By 2015, the largest source (60%) of new immigrants in Canada were from Asia (including the Middle East). Africa had also surpassed Europe as the 2nd highest source (13.4%) of new immigrants.8 By 2017, 75% of Canada’s net annual population growth came from immigration.

During Harper’s tenure, Canada’s international reputation with regards to multiculturalism and immigration likely reached its peak. Canada stood out as a positive example of mixing cultures and peoples—usually juxtaposed against the United States. In Canada, even the word ‘immigrant’ had disappeared from popular usage, with ‘newcomers’ and ‘new Canadians’ substituted in its place.

With his electoral win, Justin was no longer only the heir to Pierre Trudeau, but also his father’s tower of multiculturalism and Canadian identity.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau may have carried on the appearances and energy of his father Pierre, but it soon became clear he did not inherit his dad’s intellectual curiosity, verbal wit, dispassionate political philosophy, or couth in enacting reform. But in Justin’s defense, it was more important to many that he shared his father’s name.

Still, Justin understood the spirit of the times. ‘Progress’ and change were moral goods to be pursued for their own sake. It was simply self-evident that those chosen to run the country should be evaluated foremost on their marginal status—rather than merit or aptitude:

The Liberal approach under Justin Trudeau to multiculturalism and immigration accelerated trends that had not been significantly challenged since the 1960s. But in comparison to other Prime Minister’s with long stays in office, like his father—or Prime Ministers Mulroney, Chrétien, or Harper—Justin’s changes to Canadian identity and character would be quicker, messier, and far more transformative.

In 2015, Prime Minister Trudeau told New York Times Magazine, “there is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada,” [and that] “makes us the first post-national state.”9 Trudeau embarked on a journey to cement this vision he inherited from his dad.

The creation of the CBC, the enforcement of bilingualism, changing our flag, commissions and inquiries into accommodation, the promotion of cultural festivals, quotas in broadcasting—all these efforts over the last century to instill multiculturalism in Canada—have been surpassed by the immigration policy of Justin Trudeau’s governments.

Multiculturalism and Mass Immigration, 2016-2024

On November 1, 2017, Ahmed Hussen, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, announced the new Liberal governments’ “unprecedented plans” to build on already historically high immigration levels.

Hussen, himself a refugee from Somalia, made a case for raising immigration targets further—to replace an aging population in the workforce:

in 1971 there were 6.6 people of working age for each senior. By 2012 that ratio of worker to retiree had dropped to 4.1 to one. And projections put the ratio at two to one by 2036, less than 20 years from now. Five million Canadians are set to retire by then… if we're going to be able to commit to keep our commitments for health care, for pensions, and all of our other social programs, and to continue to grow our economy and meet our labour market needs, in the decades to come we must respond to this clear demographic challenge.10 (italics added)

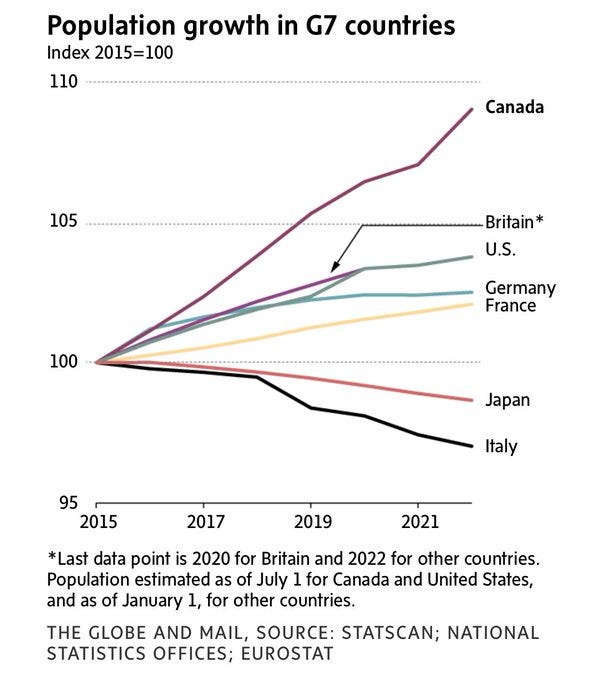

Canada’s immigration system then broke away from all norms in comparable countries, or Canada’s recent past:

This rushed attempt to renew Canada has not led to formation—in which Canada becomes a greater version of itself, and expands into a coherent structure. But transformation—in which we become “less of ourselves and more of the other”.

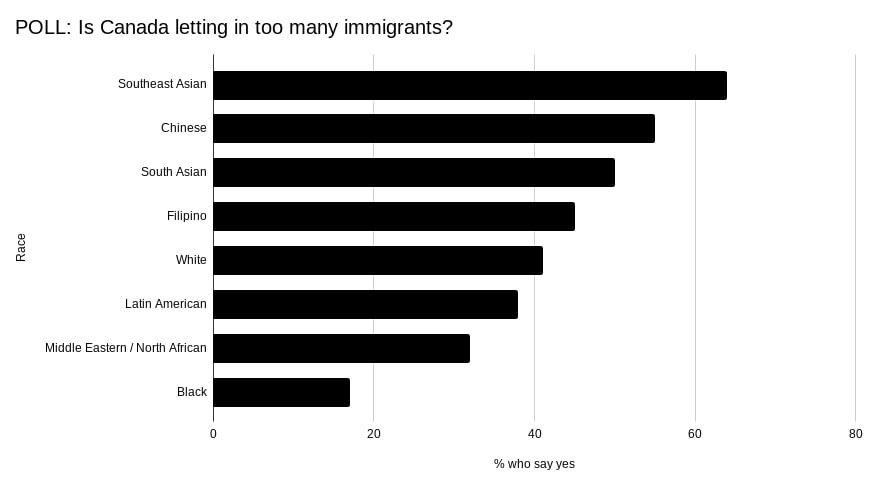

Canada’s once unquestioned, positive consensus on immigration, has begun to unravel. Views have become mainstream that would have led to one’s marginalization a few years ago.

One poll in August 2024 found 65% of Canadians believe the current federal immigration plan will admit too many immigrants, with 72% believing that Canada’s immigration policy is ‘too generous’.11

This has extended to ‘new Canadians’ as well. In April 2024, Leger12 polled those who arrived to Canada in past 10 years about the government’s immigration plans for the next few years. 42% surveyed said the Trudeau Liberals’ new immigration plan will admit too many immigrants into the country. Here this data is broken down by demographic:

From 2018-2024, India has been the top source country for permanent residents in Canada, followed either by China or the Philippines.13 Even these peoples on the margins, who have aided in facilitating change in Canada, have taken issue with the rapid transformation of the country since they arrived.

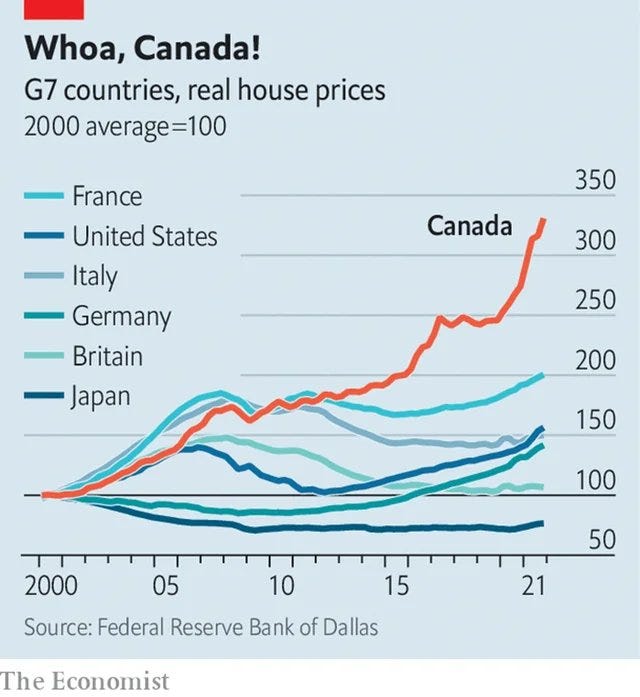

There is no area of Canadian society that has been unaffected by these changes. But housing may be the most illustrative and is unfortunately, the most symbolically appropriate—as many younger Canadians have been prevented from having a place of their own to call home.

Canada’s implementation of mass immigration in recent years has been an entirely uncontroversial, bi-partisan effort—garnering wide support from all major political parties14, and at the provincial level across the country—regardless of which parties are in office.

In June 2024, Liberal MP David McGuinty, the chair of the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, reported “[findings of] foreign interference at every order of government, in every political party, in the public sector, the media, the NGO sector, the private sector.”15 This included members of Parliament “wittingly assisting” foreign state actors. China and India were said to be the most active in these schemes.

And yet, there’s been muted reactions to this news, and Canadians still have no idea who is engaged in potentially treasonous activities in Parliament.

Beyond compromised political representatives, who have no interest in resisting the transformation of Canada, there is also wide acceptance for mass immigration from big business.

The last number of years have been great for senior business leaders in several areas of the economy—real estate investors, landlords, university administrations, agriculture, food services, construction, technology, and others have benefitted from increased competition to drive down wages, and increased demand to drive up prices of their services.

The pursuit of economic renewal and the multicultural ideal has undoubtedly produced economic benefits for a select few. But these gains have come at a cost to many. Sudden population growth puts a strain on healthcare, education, the job market, rental prices, and general infrastructure. Not to mention the unquantifiable social effects of making many neighbourhoods, towns, and cities unrecognizable.

Canada was likened to a bustling railway station at the turn of the twentieth century; a liminal space for travelers on their journey to the greener pastures of the United States. Today’s Canada could be described along these lines as an overcrowded international airport.

Novel criminal activity has been introduced to Canada as well as of late: from human trafficking in small-town Saskatchewan16, to the largest gold heist in the country’s history at Toronto’s airport17, arson extortion schemes in Edmonton, Alberta,18 or massive international call-centre phone scams19 to name a few.

Beyond criminal activity, we can look all the way back to the violence and disorder caused by groups like the Orange Order or the Fenians to know that passionate concerns of the homeland often accompany new arrivals to Canada.

We can see that adopting a post-modern Canadian attitude—which separates values from culture, ethnicity, or religion—does not come quickly for some ‘new Canadians’. Today, many Canadian cities have become microcosmic battlegrounds for the ethnic, political, and religious conflicts of the world.

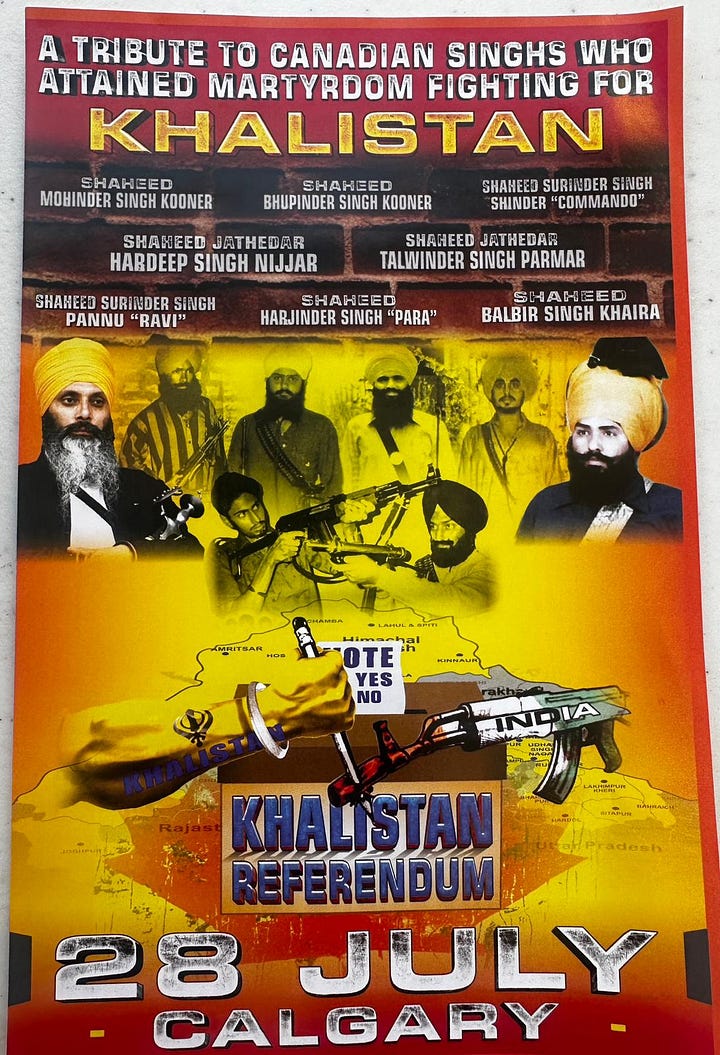

Babbar Khalsa, a Khalistani separatist and terrorist group, was implicated in the 1985 bombing of Air India 182—the worst terrorist attack in Canadian history. All 329 people on board were killed, including 268 Canadian citizens—mostly of Indian descent.

In June 2023, three Indian nationals with links to organized crime were arrested for the murder of Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Surrey, B.C. The Indian government had accused Nijjar of being a terrorist. In October 2024, Canada expelled India’s top diplomat, along with five others identified as persons of interest related to the planning of the murder.

CBC News reported that at least two of Nijjar’s alleged killers came to Canada as international students.20

The product of importing these competing concerns and allegiances is not a formation of a nation—comprised of citizens with shared duties and values, capable of a common vision.

Even excluding the more extreme cases of violence and discrimination, competing identity groups in Canada are all but encouraged to function as enclaves and patronage networks—forgoing integration in favour of preserving their position on the margins.

Canadians are often called to pick sides amongst competing identity groups—pressed to shoulder the moral weight and responsibility towards far-away conflicts. But, through the safety of a proxy, aligning with a particular marginal group offers Canadians an outlet for nationalistic sentiment—which they otherwise deny themselves.

Of course, Canada is not unique when it comes to these changes brought by mass immigration. Canada’s reasoning behind this process (multiculturalism) may be different, but the entire Western world has followed down a similar path.

Canada has always been on the periphery of great empires, and like the provincials of the ancient world, we often attempt to ‘impress the capital’ by acting as a vanguard—accelerating and embracing change.

Nations like Britain, France, Germany, and the United States have stronger centres, deeper traditions and customs than Canada, and they have also been deeply affected by similar transformation from the margins.

Some of these other countries have offered far more resistance to this process than Canadians.

Part of why similar reactions haven’t materialized in Canada is because our transformation has not been as flashy, destructive, or eventful as other nations. In true Canadian fashion, we have done it in a boring way—almost entirely legally, calmly, and without many really noticing until very recently.

Record numbers of total immigration in the last number of years is a primary cause—but this has been done in a number of ways, and at a scale that most would think is not possible.

Many have become familiar with the increases of temporary foreign workers as of late21, but are unaware of other specific programs like the Global Talent Stream, or the expansion of the International Mobility Program.22 The IMP for example does not require a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA), like the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. An LMIA requires a business to demonstrate that no Canadian worker or permanent resident is available to fill a position, to then seek out a temporary foreign worker.

There is a website to look in your town or city to see businesses in Canada that have received positive LMIA’s.

People who should be sounding the alarm with these programs— like those who are ostensibly aligned with unions or champion the rights of workers—have taken little issue with these enormous sources of exploitation, wage suppression and what is effectively, global scab labour.

Recently there have also been headlines about the numbers of international students in Canada. In 2023, 1 out of 40 people in Canada were international students. India alone accounts for around 40% of all international students in Canada.23 The United States, with roughly 10x Canada’s population, had about the same total amount of international students.

Post-secondary institutions have reaped the benefits of enticing the one percenters of the Third World to gamble their resources towards funding their studies in Canada. And many businesses benefit from the competition they bring to low-wage jobs to stay here.

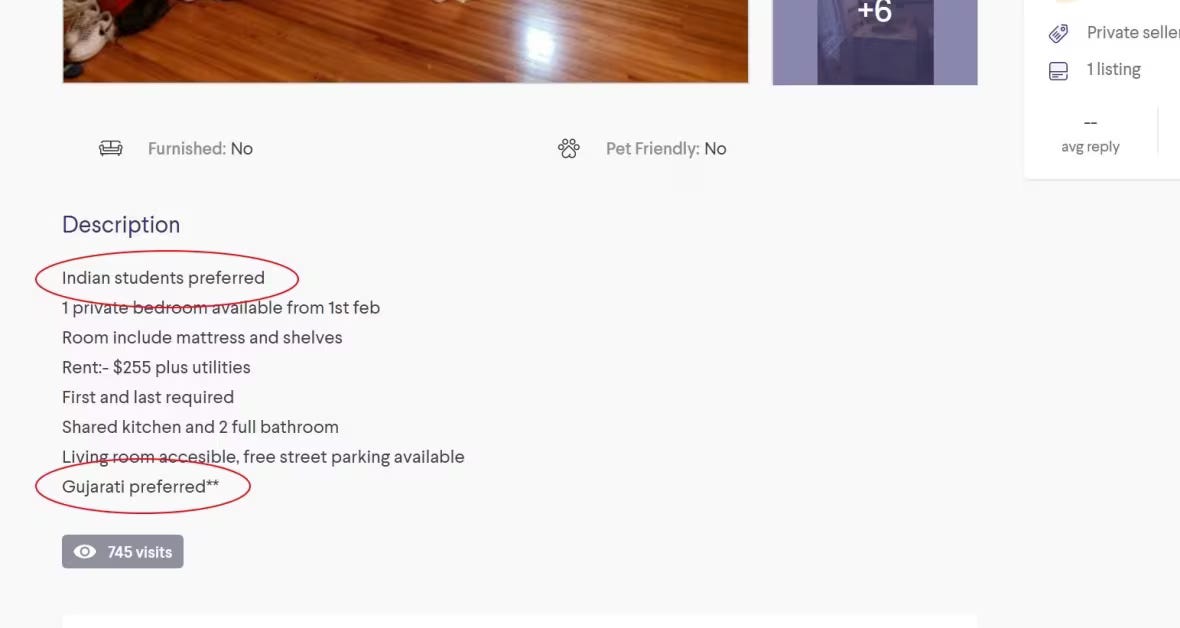

There is an entire genre of videos online, aimed at international students, on how to game and scam Canadian programs. Recently, the Greater Vancouver Food Bank banned first-year international students from accessing its services.

In 2024 alone, nearly 13,000 international students applied for asylum as refugees to stay in Canada once their visas run out.24

Radio-Canada recently investigated online networks offering to bring Indian migrants in Quebec to the U.S. for a price—openly advertising their services on TikTok.25 More than 18,000 apprehensions have been recorded by U.S. Border Patrol at the Canada-U.S. border between January and August 2024.26

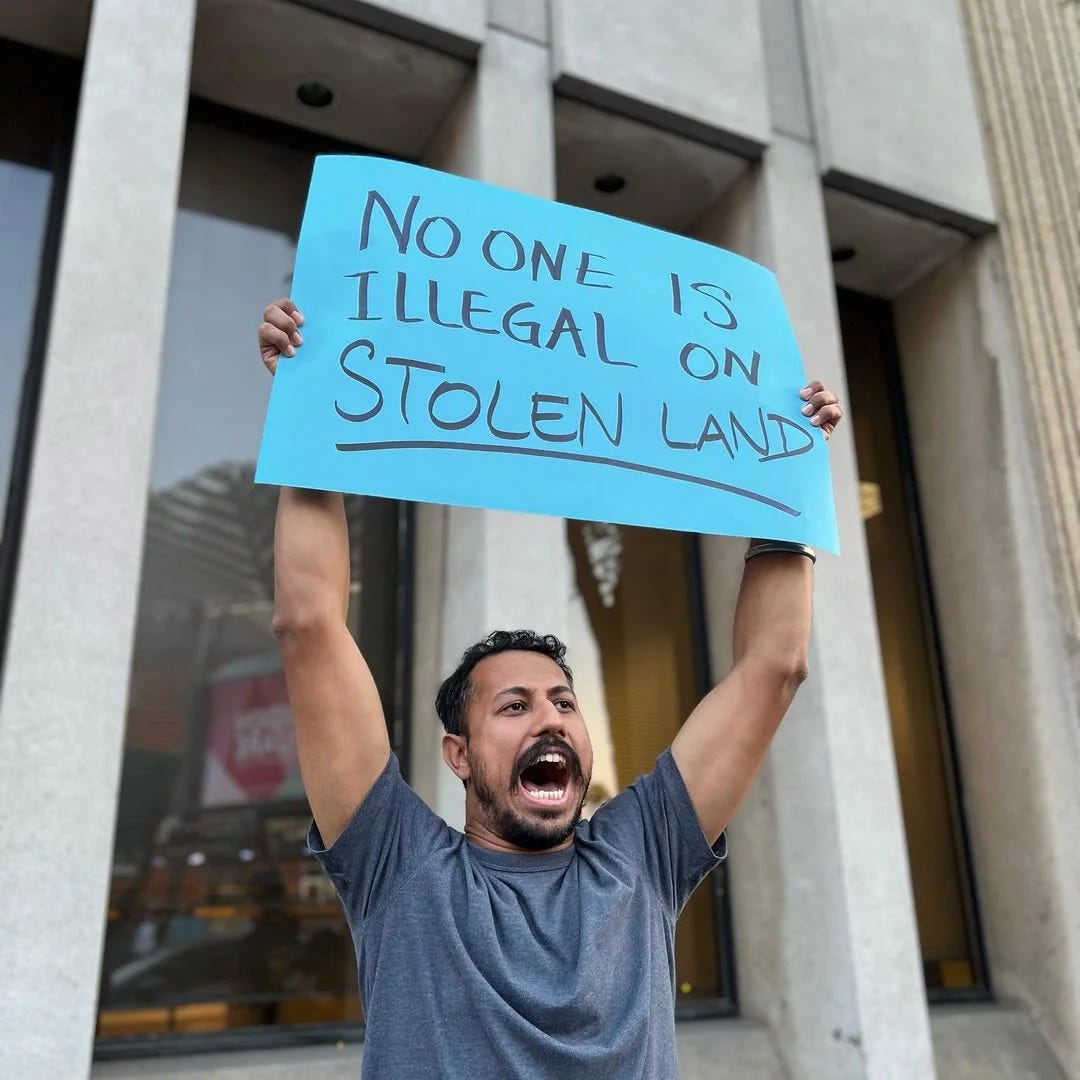

The often used justification of mass immigration—as a sort of karmic justice for the crimes of colonialism—reveals the easy exploitability of today’s multicultural project. Canada’s deferential and welcoming approach to the margins is often interpreted as weakness—and met with resentment and entitlement.

Despite this, in 2023, the federal government continued their efforts to welcome some of the most marginal and vulnerable. That year, Canadian taxpayers spent $769,000,000 to provide free hotel rooms and meals for refugees and illegal immigrants.27

In July 2024, Immigration Minister Marc Miller floated the idea of the federal government purchasing hotels outright to house asylum claimants while they wait for their cases to be processed—having already paid for 4,000 hotel rooms for 7,300 asylum seekers in the first half of 2024 alone.28

In 2021, before the recent extreme ramping up of immigration, Canada was already home to five out of the top six cities in the world by percentage of foreign-born residents. In 2021, Canada’s largest city, Toronto, along with Brampton, Mississauga, and Surrey B.C., were already majority foreign-born, with Vancouver at 48.8%.29

There is no end point in sight for this transformation of Canada. As Canadian leadership continues to justify these changes by the tenets of multiculturalism, the state’s means of control to combat dissent, and implement their vision, only become more powerful. While the aims of our society—beyond transforming Canada further, only grows vaguer.

Part Two

N.I.C.E. Canadians

There has been a rapid amount of change in a short period of time in Canada. It may help us to once again step outside of our post-modern worldview, away from the facts and figures, to understand symbolically how and why this has happened.

C.S. Lewis, known for The Chronicles of Narnia, often used ancient patterns and symbols in his writing—similar to his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien. The title for Lewis’s science fiction book That Hideous Strength came from a 1555 work by Scottish poet Sir David Lyndsay. Lyndsay’s work describes the Tower of Babel:

That quhen the Sonne is at the hycht,

Att nonne quhen it doith schyne most brycht,

The schaddow of that hydduous strenth,

Sax myle and more, it is of lenth.

(That when the sun is at the height, at noon when it does shine most bright,

the shadow of that hideous strength, six miles and more, it is of length.)30

Lewis published That Hideous Strength in 1945. It is set in what was then modern-day Britain. The story is centred on the activities of the National Institute for Co-ordinated Experiments (N.I.C.E.). A powerful and influential group of highly esteemed scientists and intellectuals.

On the surface, N.I.C.E. appears committed to scientific inquiry and the improvement of humanity—with technocratic plans to ‘recondition’ society for the better.

N.I.C.E. attempts to reach past humanity’s political, cultural, and biological norms, and harnesses technological power to totally reshape the world. They commune with dark forces to reach their goals, but this also creates an opening for good supernatural forces to join the fight as well.

The builders of Babel, the N.I.C.E. Institute in That Hideous Strength, and proponents of multiculturalism in Canada, attempt to ‘reach heaven’ by controlling the means of renewal—building a tower of meaning and inclusion capable of integrating all peoples and cultures.

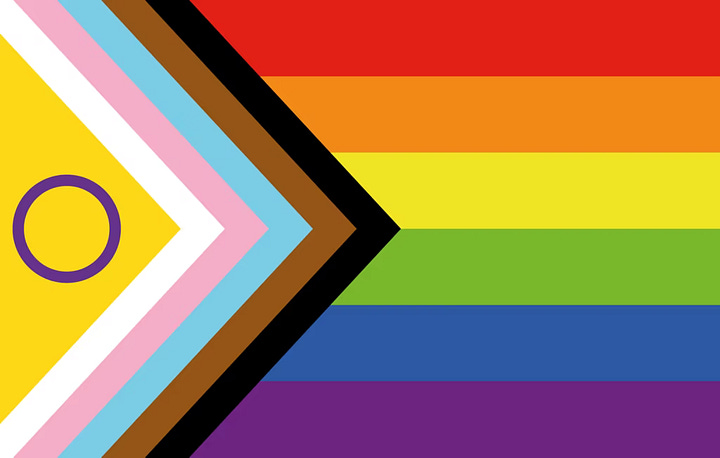

In That Hideous Strength and in Canada, new identities and customs are created by casting out traditional mores, new symbols have emerged to accompany these changes, and all of this is achieved under the guidance of enlightened technocrats, with a global outlook, and expressed politely and congenially. Afterall, Canadians are known for being N.I.C.E.

But in practice, any campaign to establish or renew a political community, or integrate disparate groups of people, requires a considerable amount of coercion and force, comes at considerable cost, and can also enhance a leader’s control.

The idea in Canada that we can renew ourselves primarily through immigration, is built on a denial of difference—rather than a celebration of diversity. The notion that the entire world are potential ‘new Canadians’ erases the variance and contrasts between cultures—sorting everyone into economic units that can be moved around at will.

This philosophy requires a number of presuppositions about Man and our nature. As does the popular sentiment which usually accompanies this sort of thinking, which says, ‘where you are from is just an accident of birth’.

This requires an Origenist31 view of the pre-existence of souls. Where there is a sort of ‘soul lottery’, in which we are randomly assigned into a body upon conception. But we can reject this outright, and assert that the premise itself is nonsensical.

The Christian belief—belonging more to the ancient worldview than popular notions today—is that a soul is necessarily tied to a body, and there is no separation of the two before birth. And ultimately, both are to be joined together again after the world ends.

This means that, regardless of who we are, there is no randomness to our origin. We could not have been born in a different place, or to different parents, or into the ‘wrong body’. Its not an ‘accident’ that we happen to be who we are. We could’ve only been ourselves.

Even without bringing philosophy or theology into the discussion, this is biologically true. We are necessarily the sum of the lives and choices of our ancestors. They are not strangers to us—in a sense they are us literally—we share their DNA. The attempt to renew ourselves primarily through other people and their children, denies this reality.

Today, Canadians occupy an in-between position in regards to our past. In the cases of the misdeeds of our European ancestors, there is a clear causality between their actions and us, and we inherit guilt for their crimes. But in recognizing any positive attributes of our ancestors, we say its simply prideful and pathetic to take any credit for the actions of people we never met or knew.

These contradictory and confused ways of looking at the past have the effect of us simply forgetting who we are. History is the record of being and belonging, and when we forget our own story, we lose the ability to understand ourselves.

In 2019, the longtime hockey commentator Don Cherry infamously alluded to how, he felt, some of Canada’s shared remembrances and rituals had become neglected. Cherry had always been outspoken in his support of Canadian veterans, and frequently promoted the practice of wearing of poppies in the lead-up to Remembrance Day; inspired by the war poem “In Flanders Fields”:

Cherry was fired for his comments. He was voted by viewers of the 2004 CBC miniseries The Greatest Canadian as the seventh-greatest Canadian of all time.

The Falling Tower

Younger Canadians are poised to not only forget ourselves, but to lose the ability to continue on at all. Canada has possibly permanently altered its cultural, economic, and spiritual ‘reproductive systems’.

Canada is among the world leaders of ‘gender-transition’ practices, permissive abortion policies, and low fertility rates. In recent years, we have experienced record deaths from drug overdoses, and implemented the world’s fastest-growing euthanasia program.32

These are all symptoms, or symbols, which show us on a path away from integration and renewal—towards confusion and death.

Usually referred to by its acronym, MAiD (pronounced ‘made’) is Medical Assistance in Dying—Canada’s practice of doctors and nurse practitioners killing patients with an injection of drugs at their request.

In 2021, changes came into effect, to allow MAiD for eligible persons who wish to pursue a medically assisted death “whether their natural death is reasonably foreseeable or not.”33

Reporting has shown that those on the margins are increasingly seeking MAID, or having the practice suggested to them: “A homeless man refusing long-term care, a woman with severe obesity, an injured worker given meager government assistance, and grieving new widows” are just some examples.34

Another MAiD case was recently described in The Globe and Mail:

A man in his 40s with inflammatory bowel disease who was socially isolated and addicted to opioids and alcohol was told about MAID during a psychiatric assessment. His family wasn’t consulted beforehand, and the MAID provider drove him to the location where he received an assisted death.35

MAiD captures how much of recent changes to Canada rely on Canadian’s polite and often standoffish nature, and not looking too deeply into what things like ‘reproductive healthcare’, ‘supervised consumption’ sites, ‘gender-affirming’ practices, or ‘medical assistance in dying’, can actually mean in practice. This prevalence of euphemisms and indirect language to describe things we’d rather not talk about, is a way Canadians remain quite British.

These policies also reveal that there is only so far we can push change, before the entire social order is effected. Like the Tower of Babel, as tall and ‘hideously strong’ as things can appear—some impositions of order prove to be quite fragile.

The Book of Genesis never actually states how or if the Tower of Babel fell. But the Book of Jubilees—a pseudepigraphal work (not actually in the Bible)—speaks about the common ancient understanding; which is that God breathed a mighty wind to knock the tower down, and then sent the peoples scattering.36

Today, the winds are blowing against Canada’s multicultural tower. Much of the reaction against the established order of today has been targeted at Justin Trudeau. He has received more vitriol and personal animosity than perhaps any other Prime Minister—even surpassing his father.

Most people understand reality through narrative, story, and characters. So although its not very constructive, they are not technically wrong to direct their ire towards Canada’s ‘main character’ of today—who also happens to be the literal heir and steward of Canadian identity.

Those who oppose today’s established order, often end-up identifying themselves with the margins.

We saw this with the 2022 convoy protest, also known as the ‘Freedom Convoy’, against COVID-19 vaccine mandates. Prime Minister Trudeau characterized the protestors as a “small, fringe minority” who held “unacceptable views”. The truckers and their supporters embraced this position.37

To seriously contend with our recent transformation, Canadians would need to reorient our entire worldview—to not place the margins above all else. And to advocate for Canada for its own sake—as a centre that is worth preserving. But getting Canadians to be unapologetic about themselves is a big ask.

Quebec has often not had this issue. Quebec’s nationhood and distinct character had always been self-evident to many Quebecers. But we have seen that Quebec’s attempts to express or codify their sovereignty through political means has proven difficult—having hollowed out its spiritual foundations in pursuit of a national identity.

Quebec’s position in Canada mirrors the global context of our country as a whole. At the global level, Canada itself is marginal. We are a small and fragile nation that will not be able to contend for long with our doors open to the entire world.

Advocates of multiculturalism may see the current state of Canada like the growth pangs on a spiritual journey, where we are undergoing a multicultural ‘dark night of the soul’—a great crisis of faith and confidence before we ultimately achieve a long-lasting peace and fulfillment.

Loving Your Neighbour

Keeping English and French Canada united was the original intent behind the creation of Canada as a nation, and the installment of multiculturalism as our national identity. We came together instead of just becoming Americans.

But attempting to maintain a separate identity from the most powerful and culturally influential nation on earth—with whom you share the much of the same heritage, culture, and language—was always going to be losing fight.

Once Canada cast aside much of our British and French inheritances in the middle of the 20th century, we simply switched from our colonial British status, to becoming a ward of the United States. Like many Western countries, Canadian attempts to protect against or contain American cultural, economic, and political dominance, have been unsuccessful.

A future historian might argue that Canada never evolved into a sovereign nation in the first place—changing little from the fur trading days of the Hudson’s Bay Company or the colonial railroad era: remaining a continent-spanning company town or economic zone; ruled by a small, wealthy political and business elite beholden to imperial masters; an economy based on resource extraction, land speculation, and ‘coolie’ labour; and a culture and politics which ignores our own affairs—preferring the goings-on in the homeland or the capital of the empire.

The Canadian attempt to build an identity by centring the margins—to capture and contain fluidity itself, has proven difficult.

The ancient understanding of the centre and margins easily map onto our highest secular demarcations of value and identity: oppressor vs oppressed, colonizer vs the colonized, ‘racialized’ vs ‘settler’, etc.

But the margins never stay still. They continue their encroachment, first on what is left of the centre, but also upon the tentative coalition of the margins themselves.

We can see in these sometimes conflicting marginal symbols and demonstrations, that the hallmarks of religious practice: worship, confession, iconography, genuflection, adoration, communal chanting, blasphemy, penance etc. have not been done away with at all in our ‘secular’ culture—only redirected, as a privation of their proper form.

Canada’s recent transformation is only a small part of a global pattern. The attention and focus of world politics have been directed towards the margins, and the questions surrounding their integration.

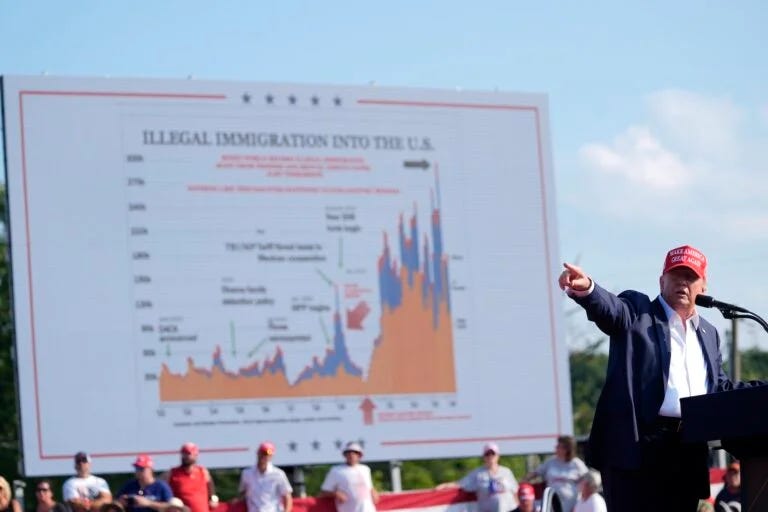

The most famous and polarizing man alive today, and soon to be once again the ‘leader of the free world’, gathered attention upon himself due to his focus on the margins—and borders, and the failed integration and renewal brought by mass immigration to the United States.

Canadians have had great difficulty understanding the Donald Trump phenomenon. But his rise has followed these same basic patterns we have been speaking about in Canada.

Trump has gathered together a plurality of Americans, who feel they’ve been forgotten by their leaders. For this ‘silent majority’, enough transformation has taken place that they feel pushed to the margins themselves.

These ‘forgotten men and women’ have turned to an unapologetic, political outsider to take back the centre, and instill formation—change which produces “more of itself and less of the other”. In other words, to ‘Make America Great Again’.

Canada’s role in this larger story highlights that being an heir carries along enormous responsibility—regardless of what you inherit. Natural splendor, geographic favour, security, economic prosperity, or even a distinct sense of who you are, can all be taken for granted. Hundreds of years of tradition, ritual, peace, order, and good government can be irrevocably lost in a single generation.

We’ve seen reactions against the Church attempting to accommodate the world at the same time similar feelings are being expressed politically in Canada and elsewhere.

Renewed interests in more traditional forms of worship, such as the Latin Mass, the recent rise in converts to Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism, and the enthusiasm towards rediscovering the ancient worldview—all show that a sizeable amount of people do not want to be accommodated. They are looking for something that the world can’t give them.

And what they are looking for are those fundamental truths about reality which are embodied in traditions and ancient stories. This is where we can find the correct forms of the virtues we try and mimic through multiculturalism and other ‘secular’ values.

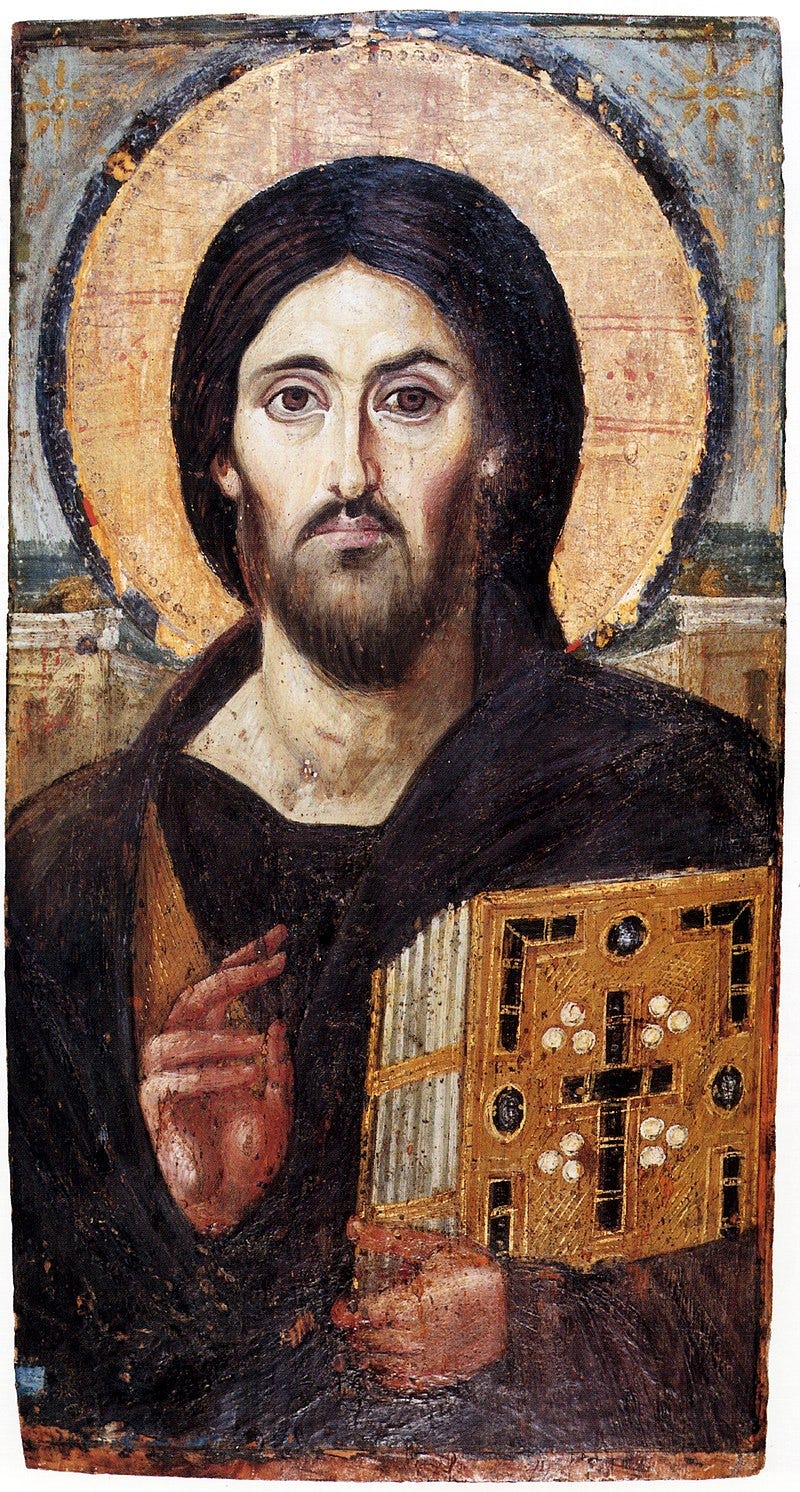

In Christ we can see the perfect integration and renewal of the centre and the margins. Christ embodies the lowly position of the margins—as a refugee, prisoner, and victim of injustice and persecution. He also occupies the highest authority of the centre—as a priest, king, and the Son of God.

The crown of thorns is a potent example of Christ’s dual position on the margins and the centre. What was intended to denigrate, humiliate, and mock Him only allows the complexity and completeness of His kingship, authority, and mission to shine through further.

Canadian multiculturalism only sees one side of this dual position. Emptying ourselves of identity, we pursue negation for its own sake. We want the thorns without the crown; the cross without Christ.38

But Christ is always acting in full accordance with His mission. He orients us by becoming the tower—as he is raised up on the cross. He then descends into the depths of hell, to triumph over death, and renew mankind’s fall.

It is this redemptive element which multiculturalism also lacks. Conversely, Christ is the Judge of sin, but is also the Saviour. He takes our sins upon Himself—as if He were guilty. There are clear ways to be both forgiven and saved by Him.

Christ’s mission also leads to a resolution of the Tower of Babel. 50 days after His resurrection, the same wind which descended to destroy the Tower of Babel, reappears. This time, the wind forms each of the Apostles into towers themselves.39 The Holy Spirit turns them into illuminated focal points—giving them the ability to orient others as Christ does.

2 And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting.

3 And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them.

4 And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

5 And there were dwelling at Jerusalem Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven.

6 Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together, and were confounded, because that every man heard them speak in his own language.40

Babel and Pentecost give us the ‘grammar’ to understand the difference between artificial and true unity, love, and sacrifice. On Pentecost, every man who is oriented properly hears the Word in his own language—those who are not oriented properly, continue to hear babble.

Western democracies appear to be in a liminal state. The ideas we hold about the proper role of the centre and the margins are being tested. The residual Christian virtues and ideas which have inspired rapid change are looking for their proper expression.

Its difficult to see how long this transitional period will last, and what will come after. Its possible that Canada has simply sped up some of the inherent contradictions of our age quicker than other countries. Of course, we have a front row seat to see how the most powerful country on earth navigates these times. We will undoubtedly be effected by this.

If we are nearing the end of the political and cultural world we find ourselves in, and beginning another, then in this space between worlds, we should reengage with those ancient stories, patterns, and traditions which put things into their proper place.

In this pursuit, we can become towers ourselves. Being properly oriented, we can embody these virtues which have been let loose, learn how to act as worthy heirs, and stand a chance to achieve a genuine renewal.

30 And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment.

31 And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.41

Pageau, Matthieu. The Language of Creation: Cosmic Symbolism in Genesis: A Commentary. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, May 2018), 135-36.

Pageau, Jonathan. The Odd Double Symbolism of the Margins | Jonathan Pageau.

“Father of drowned Syrian boy Alan Kurdi blames Canada for death of wife and son”. CBC News, September 11, 2015.

“Aunt of Alan Kurdi, drowned Syrian boy, did not apply to sponsor family in Canada”. CBC News, September 3, 2015.

“Trudeau unveils plan to ‘restore democracy’”. The Canadian Press, June 16, 2015

The immigration rate per the total population under Harper’s predecessors, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin’s Liberals, ranged from a high of 0.89% in 1993 to a low of 0.58% in 1998. For Harper’s Conservatives, the number was more consistent, and higher overall—with a low of 0.72% in 2007 and high of 0.83% in 2010.

Harper also expanded The Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). TFWP more than doubled in size between 2003 and 2013, to almost 340,000 workers. Under Prime Minister Harper from 2006 to 2014, TFWP grew to about 500,000 workers, above the number of new permanent residents.

“21.9% of Canadians are immigrants, the highest share in 85 years: StatsCan.” CBC News, October 25, 2017.

“Trudeau’s Canada, Again.” New York Times Magazine, December 8, 2015.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citzenship Canada. “Speaking notes for Ahmed Hussen, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship at a news conference on Canada's Immigration Plan for 2018”. Toronto, November 1, 2017.

Leger Marketing Inc. “CANADIAN POLITICS: Immigration and the Temporary Foreign Workers Program”. August 26, 2024.

Leger Marketing Inc. “Cracking the Newcomer Code”. February 16, 2024.

Canada immigration statistics - “Annual sources of immigration”. Wikipedia.

The People’s Party of Canada, founded by Maxime Bernier in 2018, is a lone outlier in this regard. The PPC is currently (Nov. 2024) polling around 2% nationally.

“MPs 'wittingly' took part in foreign interference: national security committee”. CTV News, June 3, 2024.

'Felt trapped': In Sask. human trafficking trial, court hears woman forced into sex with employer”. CTV News, September 25, 2024.

“Additional suspect in largest gold heist in Canadian history arrested at Pearson Airport”. CityNews Toronto, May 9, 2024.

“Edmonton police charge 6 people in ‘Project Gaslight’ arson extortion case”. Global News, July 26, 2024

“These scammers called almost everyone in Canada — and swindled millions”. National Post, June 7, 2024.

“3 Indian nationals arrested for murder of Sikh activist”. CBC News, May 3, 2024.

“Liberals say they will rein in temporary foreign worker program after historic influx”. CBC News, August, 25 2024.

“Little-known program dominates Canada's massive guest-worker scheme” Vancouver Sun, September 12, 2024.

“Nearly 13K international students applied for asylum this year, data shows”. Global News, September 24, 2024.

“Smugglers are advertising illegal Canada-U.S. border crossings on TikTok”. CBC News, September 19, 2024.

“Free hotel rooms, meals for refugee applicants reportedly cost $769M in 2023”. PostMedia News, December 8, 2023.

“Federal government considers buying hotels to shelter asylum seekers”. National Post, July 4, 2024.

"Ane dialog betuix Experience and ane courteour off the miserabyll estait of the warld. Compylit be Schir Dauid Lyndesay of ye Mont Knycht alias, Lyone Kyng of Armes. And is deuidit in foure partis. As efter followis. .&c." In the digital collection Early English Books Online. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/a05548.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 12, 2024.

“Private forums show Canadian doctors struggle with euthanizing vulnerable patients”. Associated Press, October 16, 2024.

Government of Canada. “CANADA’S NEW MEDICAL ASSISTANCE IN DYING LAW” Infographic.

Ibid. “Private forums show Canadian doctors struggle with euthanizing vulnerable patients”. Associated Press, October 16, 2024.

“Rates of medical assistance in dying for non-terminal illness in Ontario higher in poorer neighbourhoods, reports say”. The Globe and Mail, October 18, 2024.

Charles, R.H. The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913. Jubilees 10:26. Scanned and Edited by Joshua Williams, Northwest Nazarene College.

Flavius Josephus, the 1st century AD Jewish historian, makes note of God blowing down the Tower of Babel using wind as well, in his work The Antiquities of the Jews, Chapter 4: “Concerning The Tower Of Babylon, And The Confusion Of Tongues”.

“‘Fringe minority’ in truck convoy with ‘unacceptable views’ don’t represent Canadians: Trudeau”. Global News, January 27, 2022.

In the introduction to Ven. Fulton Sheen’s 1977 book Life of Christ, he makes reference to the Crossless Christ and the Christless Cross—when comparing the decadent, laissez-faire western world to to the rigid, demanding totalitarian states of the 20th century—namely the Soviet Union.