In January 2025, the Liberal government appeared to be in ruins. Prime minister Justin Trudeau was terribly unpopular, and polling indicated an incoming landslide for the Conservatives in the next election. But around this time, U.S. President Donald Trump was preparing for his inauguration, and begun making headlines referring to Canada as the ‘51st state’, and calling the prime minister ‘Governor’ Trudeau.

In a previous article, we attempted to make some sense of this turbulent time:

Liberal democracies as a whole are in a liminal state. Ideas held across the Western world regarding nationhood, citizenship, and proper roles of the centre and the margins, are continually being challenged… In Canada, our marginal position in relation to the U.S. will give us front-row seats to see how to move forward—for better or worse. Entering a new year, with new leaders, Canadians and Americans should prepare once again to focus on the margins, and embrace change—because it’s

20152025.

Then, a few months later, on April 28th, 2025, a federal election saw the Liberal Party return to power just a few seats shy of a majority government, having recovered from the brink of collapse. With a new leader, the “natural governing party” regained the trust of a significant portion of Canadians, to lead them through what many viewed as an urgent crisis—American encroachment on Canadian sovereignty.

The day after the election, in resource-rich Alberta, premier Danielle Smith’s government introduced legislation to amend several voting procedures in the province, including lowering the requirements to trigger a provincial referendum on separation from the rest of Canada. Bill 54, the Election Statutes Amendment Act, 2025, passed and received Royal Assent on May 15, 2025.

Long frustrated with national energy policies and perceived deference from the federal government towards Quebec, Smith relayed the message to Ottawa that she remains in favour of “a sovereign Alberta within a united Canada”.1 However, Smith also promised to hold a referendum in 2026 if the threshold for the vote is reached.

A recent poll asked supporters of Smith’s United Conservative Party, “If a provincial referendum was held tomorrow asking Albertans if they would like to remain in Canada or become an independent country, how would you most likely vote?”, 58 per cent responded “LEAVE”.2

A reporter asked Yves-François Blanchet, leader of the Bloc Québécois, the federal Quebec separatist party, if he had any tips for the upstart separatists out West. Blanchet quipped, “The first idea is to define oneself as a nation. Therefore it requires a culture of their own, and I am not certain that oil and gas qualify to define a culture.”

Halfway through 2025, amidst renewed calls for separation and issues of sovereignty taking centre stage, it may prove useful to examine the last time a Canadian province attempted to go on their own.

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One

In the late 80s and early 90s, Canada’s federal politics was often consumed by regional infighting, focused on many of the same issues we are dealing with today. Prime minister Brian Mulroney made several attempts to accomodate a province which was threatening to separate. An anglophone Quebecer, Mulroney tried repeatedly to amend the constitution which Quebec had left unsigned since 1982. These failed attempts would have recognized Quebec as a distinct society within Canada and granted the province greater autonomy.

Around this time, new regional parties emerged on the federal level, which attempted to fill in the cracks where compromise had failed. Out West, the Reform Party was founded in 1987 and led by Preston Manning. Manning’s father Ernest dominated Alberta politics, as a longtime premier of the province from 1943-1968. Preston followed in his dad’s footsteps, corralling a base of social and fiscal conservatives, rural voters, and urban business interests, to form a centre-right party to rival Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives.

In 1989, Reform won its first seat, and by 1993 they had 52. Reform was propelled to national relevance by Western Canadians who were frustrated with a poor economy, and what appeared to them to be Quebec getting special treatment from the federal government. Still, Reform’s reach was limited—only capturing one seat east of Ontario, and none in Quebec.

The Eastern equivalent of the Reform Party was the newly formed Bloc Québécois, founded by Lucien Bouchard in 1991. Bouchard had been a close friend of prime minister Mulroney, and served in his cabinet. Bouchard left his cabinet position and started a party of his own following the failures to reform the constitution. The Bloc was founded to advocate for Quebec sovereignty and to push for separation from the rest of Canada.

In the 1993 federal election, the Bloc won 54 out of 75 seats in Quebec. The splitting of support towards Reform in the West, and the Bloc in the East, aided in the total collapse of the Progressive Conservatives, who were reduced from 156 seats to 2. This led to the Liberal Party forming government, and resuming their natural place in the minds of many Canadians as trustworthy stewards in times of crisis.

The following year, the 1994 Quebec election saw the separatist Parti Québécois gain power in the province again, now led by Jacques Parizeau, who had played an important role in the 1980 Quebec separatism referendum. Now as premier, he promised to call for another vote.

The 95 Referendum

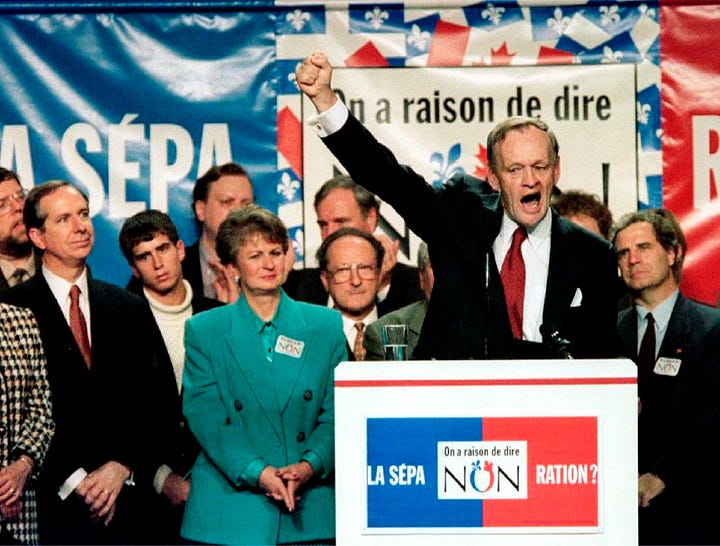

Premier Parizeau scheduled a referendum for October 30, 1995, to decide on Quebec separation for a second time. Parizeau, along with the new federal Leader of the Opposition, Lucien Bouchard, would lead the campaign of “Oui”—yes to separating from Canada.

The 1995 Quebec referendum proved to be much more closely contested than the previous attempt in 1980. On October 30, 1995, almost 5 million Quebec voters, 93% of those eligible, turned out to decide the future of the two Canadas. The margin of victory was decided by a mere 54,288 votes.

“No” to separation won 50.58% to 49.42%.

The national pact was a few thousand votes from being torn apart. The entire enterprise proved to be a hasty, gutsy, but ultimately ill-conceived offering of an alternative to the political paradigm in place since the country was formed. And the first real attempt to depart from Canada’s multicultural identity established in the 1960s and 70s.

The victory of the federalists required nearly all the major political players and parties to come together to defeat a dedicated, passionate, and unified minority—and it just barely worked.

Quebec premier Jacques Parizeau was not so gracious in defeat. Speaking the night of the referendum at Montreal’s Palais de Congrès to disappointed supporters, Parizeau infamously offered his opinion how the “Yes” campaign was defeated:

“It’s true that we have been beaten, but by what? Essentially money and ethnic votes.”3

Parizeau resigned as Quebec premier the next day.

Parizeau’s accusations of money playing a role in the defeat of the “Yes” vote were, in part, in reference to the ‘Unity Rally’ held in Montreal on October 27, 1995. Most federal political leaders in Canada attended, and Canadians from all over the country came as well. Many were aided in their transportation by corporate sponsors. Some separatists pointed to the actions of the government in organizing the rally and working with big businesses as a final attempt to strong-arm Quebec into compliance.

Parizeau later tried to clarify his comments about ‘ethnic votes’, saying, “It is not healthy in a society such as ours that groups, particularly when they come from specific cultural communities, vote 95 per cent in the same direction. That is what I tried to underline. The words were too strong, but the reality does not change.”4

Allan Woods, a journalist for the Toronto Star, details how Parizeau further attempted to put his comments into context, “Parizeau would spend the rest of his life explaining that he was speaking very narrowly about a pro-Canada coalition that had been struck by leaders of Quebec’s Italian, Greek and Jewish communities.”5

But there were others on the “Yes” side who raised farther-reaching concerns about how different groups in Canada influenced the vote. A letter sent by the federal government to new citizens, which asked them “to help build a strong and united Canada” was scrutinized by separatists.

In the leadup to the referendum, the citizenship process for new immigrants in Quebec was also fast-tracked by the federal government. Bloc Member of Parliament Osvaldo Núñez, himself an immigrant from Chile, raised these concerns in the House, just weeks before the referendum. Sergio Marchi, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, denied that the measures were anything out of the ordinary:

What is being done with respect to citizenship processing in the province of Quebec leading up to the referendum is nothing different from any lead up to any provincial campaign. My department has done likewise with the provinces of Manitoba, New Brunswick and Ontario. If we compare the number of citizenship processings with the year of the Ontario election, it is up some 45 per cent. Is the hon. member suggesting that we should somehow slow down the process? Is the hon. member suggesting that it is not proper to have the persons exercise their democratic right to vote?6

With the incredibly narrow margin in the final count, it was certainly true that every vote mattered.

Some who left their choice until the last moment may have have also been influenced by President Bill Clinton. Just five days before the vote, Henry Champ, a CBC correspondent, was asked by the Clinton administration to attend a briefing and ask a question to the President about the Quebec issue. Clinton answered:

When I was in Canada last year I said that I thought that Canada had served as a model to the United States and to the entire world — about how people of different cultures could live together in harmony — respecting their differences but working together. This vote is an internal Canadian issue for the Canadian people to decide, and I would not presume to interfere with that. I can tell you that a strong and united Canada has been wonderful partner for the United States and an incredibly important and constructive citizen throughout the entire world.7

In this case, a little American encorachment was more than welcomed by Canadian federalists.

Anyone from Anywhere

As we’ve discussed previously, if we are trying to understand relations between peoples, the symbolic terms of the centre and the margins can help.

It can challenging to identify the centre and the margins within a nation, but throughout Canadian history we can see the formation of centres within both English and French Canada, each with their own identifiable customs and traditions.

Quebec had its own centre, as a distinct society that was never fully integrated into the rest of Canada’s common English culture. The concentration of economic power in Quebec in the hands of anglophones also pushed Quebecers to the margins not only in Canada, but their own society.

Often feeling pushed to the margins, Quebec swung wildly between extremes in the 20th century. They entered the 1950s as a society which preserved what was really an 19th century way of life—with a traditional culture in which the Church continued to play a dominant role in political and cultural affairs. The Quiet Revolution of the 1960s was a strong rejection of this inheritance which they clung to for so long.

But by time of the 95 referendum, this traditional relationship of Quebec on the margins of English Canada was becoming outdated. Quebecers were being replaced as the marginal group in Canada. Just from 1986 to 1996, the numbers of visible minorities in Canada had nearly doubled—from 6.3% to 11.2% of the total population.8

From two very different perspectives, both Jacques Parizeau, and Pierre Trudeau of all people, could see the effects of the growing margins in Quebec. As Trudeau wrote in 1962, arguing against Quebec separatism:

Every national minority will find, at the very moment of its liberation, a new minority within its bosom which in turn must be allowed the right to demand its freedom. And on and on would stretch the train of revolutions…9

The influence of marginal groups in Canada has only increased since the 95 referendum. The most recent census data from 2021 shows that the numbers of visible minorities in Canada have more than doubled since 1996—from 11.2% to 25.4% of the total population.10 Updated numbers in 2026 will surely show how this change has only accelerated in recent years.

Any separatist projects will need to take this into account. And Yves-François Blanchet, and the heirs to the project of Quebec separatism, have been shaped and haunted by Parizeau’s comments for a generation. Attempts to express or codify Quebecois identity through political means have proven difficult—especially so for a culture which has hollowed out its spiritual foundations, and has been coralled into relying on language as a singular point of unification.

And yet, this doesn’t mean Monsieur Blanchet was incorrect in regards to Alberta’s situation today—language alone does not make a culture, but neither does oil and gas. In response to Blanchet’s comments, Alberta premier Danielle Smith recently attempted to define Alberta’s identity in more concrete terms:

We have a culture in Alberta. We’ve got a culture of entrepreneurship, we’ve got a culture that embraces multiculturalism, that has been built by people from all over the world. I think 163 different linguistic groups that are represented here find a way to forge an identity that’s both in keeping with their heritage, as well as embracing Alberta… We have a very different culture than Quebec cause Quebec denies all those things right, they are only about language, and I don’t think they accept the broad diversity that we do…

(From 10:27-11:31)

Much of this could’ve easily been uttered by Pierre Trudeau in 1980, or Jean Chrétien in 1995—to describe Canada, and argue that we need to stick together rather than separate.

It’s also similar to the rhetoric used by the federal Conservatives throughout the 2025 election. As Pierre Poilievre said in a campaign speech:

Ours is a nationalism not based on bloodlines, birthplace or background. Whether one’s name is Martin or Mohammad, Poilievre or Patel, Tremblay ou Tang, Singh, Smith or Steinberg… What binds us together is the Canadian promise. That anyone from anywhere can do anything—That hard work gets you a great life, in a beautiful house, on a safe street, wrapped in the protective arms of a solid border, defended by brave soldiers under our proud flag...11

The federal Conservatives and premier Smith often find common ground with the Liberals when celebrating and embracing the margins—differing little in regards to Canada’s multicultural identity, or immigration policy. In 2023, Alberta had their largest annual increase on record for new residents.12 In January 2024, premier Smith floated the idea of doubling Alberta’s population by 2050.13

Continuing this growth and forging a more comfortable economic arrangement—whether it’s with Ottawa or Washington—may be all a significant portion of Albertans are holding out hope for. Many ‘new Canadians’ in Alberta may view things in similar terms. In a possible Alberta sovereignty referendum, the influence of ‘money and ethnic votes’ may play out quite differently than it did in Quebec.

The More Things Change…

In terms of the Canada of today, perhaps the defining proof the “un-Canadianness” of Quebec separatists back in 95 was an ability to unashamedly rouse a positive sentiment about themselves. They didn’t reflexively apologize for their own existence, nor deny that they were a people in the first place. They certainly didn’t try to prove their dedication to inclusivity in a quest to exclude themselves.

Much like the 90s, the political and cultural landscape in Canada is shifting, with new chances to concentrate power in the name of reform becoming available. At the same time, many Canadians also recently chose to maintain the status quo even after a decade of radical change.

As we navigate a space between worlds, and the Canada of yesterday fades away, we can expect to see continued attempts to instill order and coherence. These efforts will help us define ourselves, and aid in the forging of new identities, and holding onto old ones.

The energy and enthusiasm behind separatism efforts and protest movements shows that there is plenty of disagreement and room for engagement regarding concepts like nationhood, sovereignty, and proper roles of the centre and the margins.

But much of this tends to ignore that major Canadian cities have become microcosmic battlegrounds for the ethnic, political, and religious conflicts of the world. The most energetic and enthusiastic separatist movement in the country is not for Quebec or Alberta, but Khalistan—to create an independent Sikh homeland in northern India. Sikh separatists have recently held large demonstrations across Canada, and called to “ambush” Indian prime minister Narendra Modi as he attends the G7 in Alberta.

The redrawing of provincial borders, or switching out of party leaders—while not addressing real threats of foreign encroachment on Canadian sovereignty—appears anachronistic and naive to effect change in an age transformed by mass immigration.

In a society which has centred the margins—valuing the outsider above all—Alberta separatists stand in a long line of those who feel justified in asserting themselves and having their voices heard. But Western Canadians frustrated with Ottawa should carefully consider the guiding principles of their endeavour.

Because a project that aims to unify by breaking apart the traditonal Canadian body politic, and furthering the interests of transnational corporations—while celebrating a lack of any particular culture, history, language, or religion in the process—may constitute a fulfillment of the Canada of today, rather than any sort of separation from it.

“Danielle Smith promises Alberta separation referendum if signatures warrant” Lisa Johnson, The Canadian Press. May 6, 2025.

“Bell: 'You should be stunned': Most Danielle Smith voters would vote for separatism — new poll”. Rick Bell, Calgary Herald, June 12, 2025.

“Money and ethnic votes’: the words that shape Jacques Parizeau’s legacy”. Allan Woods, Toronto Star, June 2, 2015.

Ibid.

Oral Question Period, October 16th, 1995.

“Breaking Point” 2005 CBC Documentary. Youtube. - Part 2 of 2.

Pierre Elliot Trudeau, “The New Treason of the Intellectuals” April, 1962. Cité libre.

“Canada First Speech / Le discours « Le Canada”. February 15, 2025.

“Alberta's population surged by record-setting 202,000 people. Here's where they all came from”. CBC News, March 27, 2024.

“Alberta government backs away from podcast comments made by Premier Smith, Calgary MLA”. CityNews Edmonton, August 9, 2024.