Today, if you ask a Canadian what defines them or symbolizes their nation, you get similar types of responses. It may vary by generation, but generally, answers will consist of some combination of politeness, natural beauty, human rights, personal freedoms, diversity, animal mascots like the beaver or moose, tolerance, and hockey. Most will also answer through negative identifiers, saying: we are not like the Americans, with their melting pot which imposes conformity—but a proud mosaic of different cultures and peoples.

Most Canadians believe that it is our differences, our non-uniformity, which form the basis of our identity. That we are multicultural, and even post-national. From a symbolic perspective, this series will trace how this thinking came to be. And how in the 20th century Canada supposedly developed past the need for the traditional markers and beliefs which typically define a nation, instead viewing itself foremost as ‘multicultural’.

“Hasn’t Canada always been multicultural?”

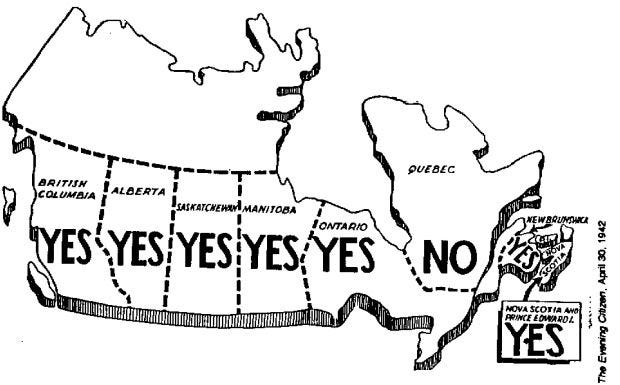

The course of Canadian history leads many to believe that through our differences we find unity. The European founders of Canada were English and French peoples with different languages, cultures, and traditions. Those who view our history through a multicultural lens often use this inheritance as a rhetorical device to claim we have always lacked a central identity. This supposed absence of identity is often one of the few positives granted to our history.

Often, the history of the English and French founders of Canada is viewed in contradictory terms. When convenient, the English and French were a diverse mix of peoples, who were tolerant of differences and blended their cultures together; like us today.

At the same time, they are also often characterized as ruthless ‘settler-colonialists’ who subjugated and oppressed Indigenous peoples, ‘stole their land’, and structured society to ensure continued European domination; also like us today.

The interactions between Canada’s two European founding peoples were not precursors to today’s coneption of a multicultural Canada. Rather, most of the history of English and French Canada should be understood as a creation of two solitudes.

A type of change occurred among both groups called “formation”, as opposed to “transformation”. Writer Matthieu Pageau distinguishes between these two different concepts of change:

formation is a process by which an identity produces “more of itself and less of the other” by integrating matter. Like the growth of a tree, this process begins with a singular identity (seed) that expands into a coherent structure. This is not change in the ancient sense of transformation, a process that creates “less of itself and more of the other”. Simply stated, change means turning something into something else, whereas formation means producing a greater version of something.1 [italics added]

For most of Canadian history, English and French Canadians were not attempting to come to a consensus by becoming “less of themselves”—as multiculturalism today calls us to do. Rather, they were constantly attempting to impose themselves onto one another, trying to become “more of themselves” whenever possible. But this is not to say that significant transformation did not occur throughout Canadian history.

All groups, whether European or Indigenous, underwent great changes to their identity as Canada developed, and entirely new societies were formed. One such example can be seen in the Métis people in the North-West, most significantly in Red River (present day Winnipeg), created out of marriages between primarily French and Scottish fur traders and their Indigenous wives.

But it should be kept in mind that these fur traders were men from the margins of their own cultures—the exception, not the rule. There was little crossover between English and French Canadians, and the Indigenous peoples of Canada prior to the settling of the North-West and the signing of the numbered treaties. There were longstanding, mutually beneficial networks of trade between the two groups, but little interaction between the centres of each people—neither group would consider the state of relations as ‘multicultural’.

Similarly, the historic relations between the English and French in Canada should be understood less as a multicultural precursor to today, and more as a centuries-long bi-cultural cold war—built on continuous compromise and detente.

Centre & Margins

In broad symbolic terms, the notion of the centre is that which is orderly, authoritative, safe, clearly defined, orthodox, traditional, or static. The margins are that which is chaotic, leftover, concealed, strange, dangerous, enticing, or foreign.

Both the centre and the margins have their own positives and negatives, and neither can be completely dominant in a society, or even in one’s own life, without introducing disorder. There is always a negotiation between how much the centre and the margins impose on one another, and where the limits are of each.

A family's home is an example of a traditional centre. Here, ideally, safety and comfort are guaranteed, order is maintained, and who is allowed to enter is highly controlled. The purpose of the home is to accommodate and provide for those within.

The front door or the porch of a family’s home is a place in-between the centre and the margins. Those from outside have limited and temporary access to this liminal space. Outside the home are the margins, where everyone from close neighbours to strangers can be found.

It is necessary and healthy to temporarily leave the centre, to engage with the margins, which can act as a source of renewal. There is inherent risk in going beyond the confines of comfort and safety. But, using the home as an example; spending too much time inside, or rarely wanting to return home, are both disordered ways of negotiating between the centre and the margins.

It can be more of a challenge to identify the centre and the margins within a nation, but throughout Canadian history we can see the formation of centres within both English and French Canada, each with their own identifiable customs and traditions.

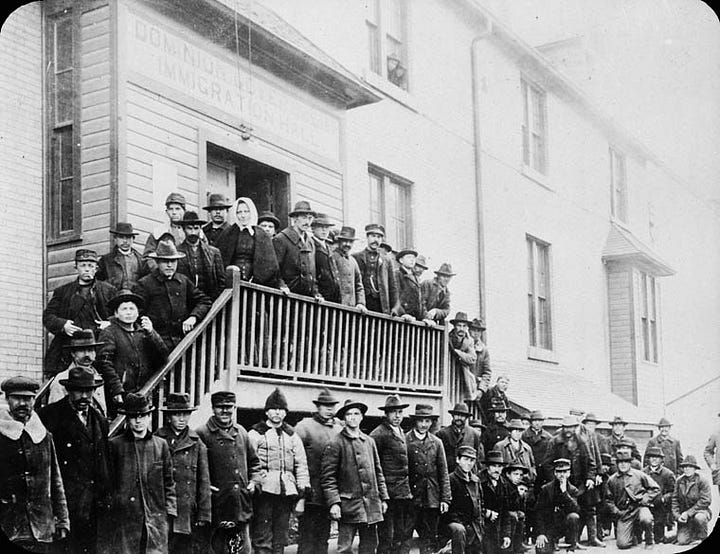

On the eve of the 20th century, both anglophone and francophone Canadians had centres with clearly established lingusitic, religious, ethnic, and cultural markers of identity and belonging. The use of mass immigration to populate the undeveloped North-West of the country would be a substantial challenge to this pattern of relations. Many of these settlers would come from non-traditional immigration source-countries, and some were only a generation removed from peasantry or serfdom.

These people gladly took a quarter-section or 160 acres of land provided by the Canadian government for homesteads, to and began to form a new agricultural society on the prairies.

Settling the North-West

Throughout Canada’s history, the North-West has symbolically functioned as the edge of the world, the margins, where identity and culture mixed in isolation. Historian Donald Creighton described Canada on the eve of the twentieth century as a railway station—a liminal space for travellers on their journey to the greener pastures of the United States. Canada suffered a net loss in population before widespread settlement of the North-West, due to the movements of people in and out of the country around this time. Between 1871-91, an estimated 1,256,000 people came to Canada, and 1,546,000 left.2

During this era, the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway was completed at great expense, but the investment was in danger of not paying off. Time was ticking. Canada was late in settling much of its western country compared to the United States. In a theme very common in Canadian history, a considerable motivation to quickly develop the North-West was to not let it succumb to an American transformation.

The threat of encroachment from the south spurred the transition of the region from buffalo hunts to widespread European settlement—all within a quarter-century. Perhaps more than any time in its history, Canada moved rapidly between worlds.

Before 1900, the overwhelming majority of immigrants to Canada were supplied from the British Isles, the United States, and small numbers of Northwestern European countries. There had been small groups which did not fit into these categories, such as African-Americans loyal to the British Crown in the east, and Chinese railroad workers in the west.

But before the North-West was widely developed, outside of the English and French, it was the Irish, Scots, and in much lesser numbers the Germans and some Scandinavians which were the only other significant immigrant groups in Canada.3

However, at the turn of the century, in the North-West, everything was subject to change: from the types of immigrants deemed ‘acceptable’, to the languages they spoke, their religious traditions, and how the landscape itself would change as agriculture took root. A glance at Canadian names of prairie towns and cities shows the mix of nationalities and cultures that began to pour in.

In many communities, an Indigenous place name was the only remnant of the former residents of the region. The beginning of the new world for immigrants in the North-West was made possible through a transformation which had ended the old world, in a single generation.

The vision of a nation stretching from sea to sea was taking shape. What started with the Fathers of Confederation, led by Canada’s first Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, would largely be fulfilled by Canada’s first French Prime Minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

Laurier assigned the task of populating the North-West to his Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton. Canadian emigration agents had made little progress in branching out on the European continent before Sifton took over the operation.

There was simply not enough of the traditional type of immigrant from Britain or northwest Europe to satisfy Canada’s needs. So, Sifton looked elsewhere. Sifton’s ideal immigrant needed to be accustomed to an identity and culture in flux, and suited to a difficult agricultural life.

At the time, soliciting emigration was illegal in many countries, and where it was not explicitly forbidden, intimidation and violence could still follow. Powerful landowners in Europe did not appreciate having their workforces poached and taken beyond their economic control.

Sifton famously referred to his archetypal North-West immigrant as a “stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children.”4 To Sifton, what these foreigners lacked in couth and civility, they made up for in their economic potential.

Several groups fit this description at the time. Life for the subsistence farmers and former serfs in Eastern Europe appeared to have crafted peoples fit for the project. Symbolically, it should not be surprising that these peoples fit into an in-between role. Often they were from landlocked regions, and the subjects of various rulers and nations—which altered their religion, language, dress, food, and cultural identity.

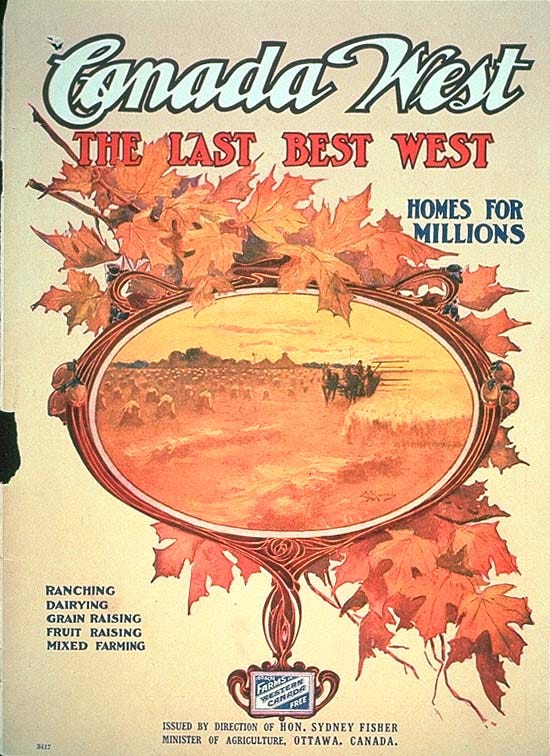

Sifton launched a new advertising campaign to entice potential settlers. The days of the American Wild West were gone, but the Canada was presented as the “The Last Best West”—the only ‘untouched’ land of the New World which was still ripe for settlement.

Sifton made a calculated risk by expanding the type of ‘acceptable’ immigrant. In symbolic terms, he went further into the margins for a source of renewal and expansion. Sifton was willing to trade short term unity and cohesion, for the goal of long-term economic development.

There were still no illusions for Sifton about the ultimate dissolution of this new mosaic of peoples. The mainstream thinking remained that these newcomers would need to be absorbed into the dominant culture—that being the English Canadian centre of society.

Resisting Transformation

J.T.M. Anderson was one of the men tasked with aiding these new immigrants in ‘becoming Canadian’. Anderson was appointed inspector of schools in the province of Saskatchewan, and then later director of education. He had a “special responsibility to ensure that school boards and teachers in ‘ethnic’ districts obeyed the law with respect to educating their children in English.”5

In 1918, Anderson wrote The Education of the New Canadian, where he outlined a plan to assimilate the new peoples of the North-West into a common Canadian culture through schooling. Anderson appeared sympathetic to the position of the new arrivals.

Anderson made references to the paths which many Canadians’ immigrant grandparents had taken. Here he makes a comparison to the Irish, who had experienced a similar journey between worlds as immigrants:

Perhaps many Canadians can recall when their grandfathers took them upon their knees and delighted to tell of their boyhood days in old Kilkenny, of the beauties of the lakes of Killarney… and very often they spoke Gaelic better than English, but to-day these sons of Canada know but little of the language of their ancestors—they all speak English. So it will be with the Canadian descendants of the Bohemian, the Hungarian, the Russian, the Pole, the German, or the Assyrian6 immigrants who have come to settle here.7

Years later, Anderson was publicly identified as associating with the Ku Klux Klan.

Pat Emmons, a Klan member, who was on trial for stealing funds from the organization, implicated Anderson in having ties to the group. This was in 1928, when Anderson was running as a member of the Conservative Party of Saskatchewan, with hopes of becoming Premier of the province.

Emmons claimed he had met with Anderson on multiple occasions, and although Anderson was not a member himself, Emmons alleged that Anderson had supplied him with a list of prominent people to recruit as Klan members.

Anderson publicly denied being a Klan member, which was actually not alleged by Emmons at all. But this intentional misdirection allowed Anderson to occupy a sort of ‘middle ground’ between voters and the Klan, as explained by historian James Pitsula:

Anderson had probably met with Emmons, as the latter alleged, but it is unlikely he joined the Klan. It would not have made sense for him to do so. Klan supporters were going to vote for him anyway. There was nothing to be gained from becoming a member, but there was much to lose. The Klan had an unsavoury reputation in some quarters, and, if it were widely known that Anderson had joined the order, some voters would definitely have turned against him. The nod-and-wink strategy was his best option.8

In 1929, Anderson won the provincial election, becoming the fifth Premier of Saskatchewan. The Klan certainly thought he would represent their interests.

The Ku Klux Klan fulfilled a similar symbolic role on the prairies as the Orange Order (a Protestant fraternal organization) did in the previous century in the province of Ontario. The two organizations deployed different means to achieve their goals, but their aims were one in the same: to promote and preserve English Canadian identity, and prevent its transformation from the encroaching margins.

The KKK was particularly strong in Saskatchewan during the 1920s. The organization adapted its ideology in Canada to address ethnic and religious issues; focusing on defending what they viewed as the rightful British and Protestant character of the nation. This was often carried out through anti-French and anti-Catholic demonstrations.

The organization’s racial focus in the United States which targeted African Americans was mostly irrelevant in a Canadian context—but Chinese immigrants and other growing minority groups were still viewed negatively.

In 1927, H.F. Emory, a Klan organizer, claimed an impressive but likely inflated membership of 46,500 in Saskatchewan alone.9 Emory explained some of the priorities of the Klan being “selection and restriction of foreign immigrants, so that Canada would be no longer the dumping ground of the world,” and “to save Canada for Canadians.”10

Prairie Pluralism

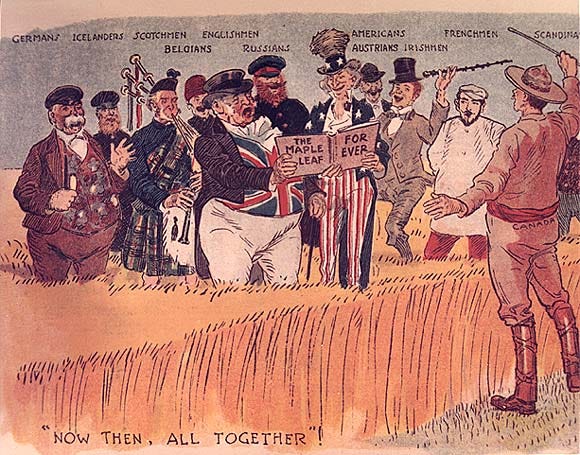

During Sifton’s tenure as Minister of the Interior, a wide variety of ethnic and religious groups came to the North-West. This included Americans from northern states such as Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Montana, and a small group of African American homesteaders from Oklahoma.11 As well as Canadians returning from the United States, and new arrivals which included English, Irish, Scottish, French, Icelanders, Scandinavians, Dutch, Germans, Austrians, Ukrainians, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, and Russians.

The religious groups were just as diverse. They included Catholics of the Latin and Greek rites, and Orthodox Churches of different countries. Plus Protestants from various denominations, such as Methodist, Lutheran, Anglican, Presbyterian, United, etc.

There were also persecuted peoples from Eastern Europe such as the Mennonites, Hutterites, Doukhobors, and Jews. Newer American religious groups made the North-West their home as well, like the Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, 7th Day Adventists, and Christian Scientists.

The growing mix of religious groups began to reshape the region. The living skies of the prairies still loomed large over the changing landscape, but small town churches soon joined the grain elevators as the only imprints of man on the horizon.

Many colonies and settlements were founded as missions or block settlements with ethnic groups in mind, with the expectation that residents would adhere to a common faith. Several could be listed, but here a just a few:

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan was founded by a Methodist group from Toronto, the Temperance Colonization Society, led by preacher John Lake, who conceived of the settlement as a refuge, free from the scourge of alcohol.

The city of Lloydminster, which lies on the border between Saskatchewan and Alberta, was similarly focused on building a society based on faith and sobriety. It was founded by the Barr colonists, named after Anglican Reverend Isaac Barr, and was intended to be a purely British settlement.

Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan is named after Father Louis-Pierre Gravel, a French Canadian priest from Quebec. The Church hierarchy sent Gravel to establish a francophone Catholic centre in the North-West, aided by block settlements of French Canadians in the surrounding area.

In 1995, Gravelbourg’s ecclesiastical buildings, the Our Lady of Assumption Co-Cathedral, Bishop’s Residence, and convent, were named a National Historic Site of Canada.

Cardston, Alberta was the first Mormon settlement in Canada; founded in 1887 by Charles Ora Card, who has been called ‘Canada’s Brigham Young.’12 Initially, Mormons came to Canada to escape anti-polygamy laws in the United States, but Canada quickly followed suit in enforcing similar laws against the growing numbers of Mormons in southern Alberta. Regardless, Mormons continued to settle the region, proving to be skilled ranchers and community builders. Over 80,000 Mormons live in Alberta today.13

Muenster, Saskatchewan was founded by German-Americans from the northern United States. Settlements like Muenster contributed to German being the second most spoken language for many years in the region, rather than French.

In need of priests, the community near the future site of Muenster had reached out to Benedictine monks from Minnesota. The monks established several churches around the area, as well as the oldest Benedictine monastery in Canada, which is still in operation. Muenster’s church, St. Peter’s Cathedral, was completed in 1910.

Peter Verigin founded Veregin, Saskatchewan. Verigin was a leader of the Doukhobors, a religious group who were persecuted in the Russian Empire for their unorthodox beliefs—which included pacifism and communal living. Their name derives from Russian Orthodox priests who called them dukhobortsy or ‘spirit-wrestlers’—meaning wrestling against the Holy Spirit.

Around 1910, there was a major split within the Doukhobors. Verigin and a majority of the Doukhobors left Saskatchewan to settle in British Columbia. They frequently ran into problems with the government, due to their refusals to accept private ownership of land, swear the oath to become a British subject, nor enroll their children in schools.

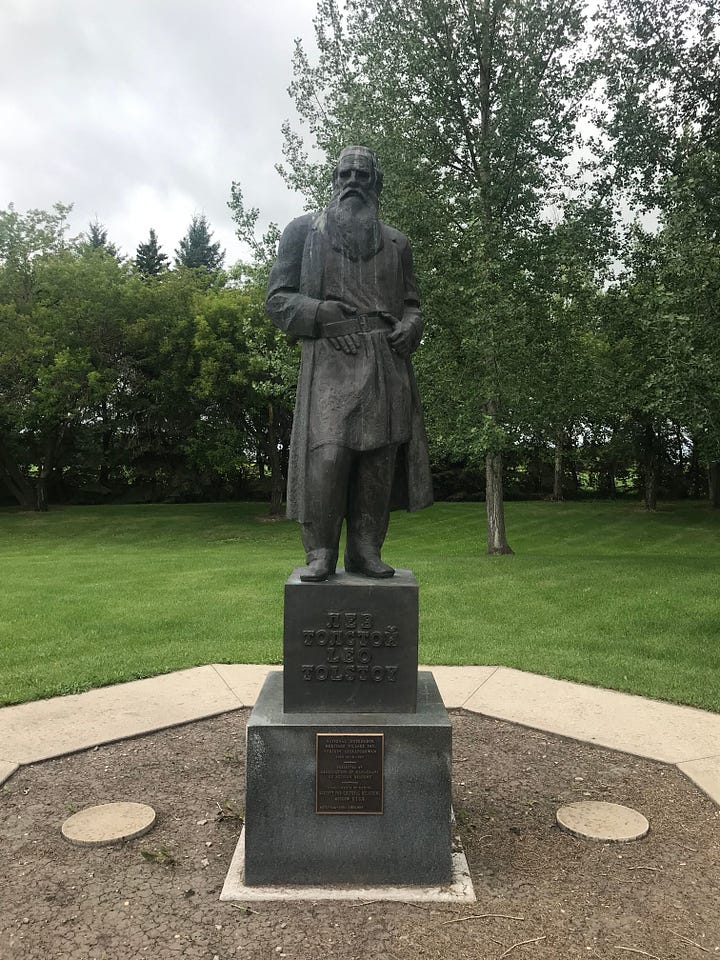

A statue of Leo Tolstoy was erected in Veregin to commemorate the writer’s sponsorship of thousands of Doukhobors to Canada. In 1924, Verigin was killed in a bombing while travelling on the Canadian Pacific Railway, in a suspected assassination.

The new mix of nationalities and religions could bring chaos and fragmentation, but it proved to form the basis of a new society on the prairies. It was a clear departure from the English and French dichotomy, which had formed traditional Canadian culture.

But, there was still a hierarchy in place, in which English and French Canadians were naturally viewed as the centre, to which the margins deferred to. At this stage in Canada’s multicultral development, the centre was able to handle and absorb encroachment from margins, without becoming consumed by them.

Authentic Renewal in the Roman Empire

It is not exactly intuitive or obvious to compare the settlement of the Canadian prairies with the spread of the Roman Empire. But here we can see an ancient understanding of hierarchy, deference, and accomadation of the margins. And how they went about incorporating new peoples into their society.

As Rome expanded and conquered new peoples, a belief was strengthened that all of Rome’s military successes were owed to a single cause—devotion to the gods and diligent religous practices. One writer explains:

The Roman conception of fortune tended to be that of which Cicero speaks: divinitus adiuncta fortuna [“Fortune divinely adjoined”]. The gods were the guardians of the city and empire. It was Roman piety that had earned their goodwill. [As Cicero also said] ‘it was by our scrupulous attention to religion and by our wise grasp of a single truth, that all things are ruled and directed by the will of the gods, that we have overcome all peoples and nations.’14

To extend this good fortune, Rome spread their customs of worship and religion to peoples that the Empire conquered. But Rome was so vast, that different peoples could be accommodated in several ways—mixing hybrid forms of different people’s indigenous practices with their own.

A passage from Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars shows the attitude of most Romans, who tended to interpret foreign deities as their own. Caesar speaks of the different gods the Gauls worship, but uses all the Roman names for them. The Gallic deities Caesar is most likely referring to are given in brackets:

They especially worship Mercury [Teutates] among the gods. There are many images of him. They claim him as the inventor of all crafts, guide for all roads and journeys; they believe that he has special power over money-making and trade. After him they worship Apollo [Benen] and Mars [Esus] and Jupiter [Taranis] and Minerva. They have about the same view of these deities as other peoples – that Apollo dispels sickness, that Minerva grants the principles of the arts and crafts, that Jupiter rules heaven, and that Mars controls wars.15

The early development of Christianity conflicted with this Roman vision of religion. The Christian refusal to sacrifice to the Roman gods was especially concerning as the imperial cult of Rome grew, and the emperor became a deity himself. Refusing to honour the gods and, by extension the emperor, was treason. Christians suffered waves of persecution because of this, and other activities which were contrary to Roman ideals.

Although they were persecuted by the state, the missionaries and leaders of the early Church also relied on the infrastructure of the Roman Empire to spread the faith. Historian Tom Holland notes how St. Paul was pragmatic about this, “If Roman power upheld the peace that enabled him to travel the world, then [St. Paul] would not jeopardize his mission by urging his converts to rebel against it. Too much was at stake.”16

St. Paul and other leaders of the early Church knew that their world-changing process of renewal and transformation could not happen all at once. Slowly, over hundreds of years, the faith spread to peoples on the margins of the Empire, and eventually Rome itself became Christian.

The centre and margins were eventually flipped. The Roman world became the Christian world. And just as they had done when adapting to Roman religious practices, those on the margins gradually found their own place in Christendom. Integration into a shared, embedded story allowed for fruitful negotiations between people's old and new identities and practices.

In Canada, the settling of the North-West had elements of this process. A great majority of new immigrants were quickly able to reconcile and integrate the culture of their homelands with their new home of Canada. Some were certainly unfamiliar or exotic, but they adhered enough to Canadian practices and customs so as to not introduce much disorder.

In plain terms, although the North-West was not populated solely by the two founding European peoples of the nation, the English and French, it was still almost exclusively European Christians who formed the new society of the prairies. The makeup of the country was still confined to a specific and well-defined portion of the world, who shared a common story, and quickly thrived in the process of ‘becoming Canadian’.

Conclusion: Multiculturalism as Failed Renewal

The multiculturalism of today has little continuity with the multiculturalism which characterized the settlement of the North-West. Today, the centre and the margins are flipped in Canada. The foreign and unfamiliar have been centred, favoured, and that which defines us, while the normative and familiar have been marginalized, and are often viewed as dangerous and threatening to the new order.

In the new multicultural Canada, subordination of identity (for members of the traditional centre) has become the highest good; something which signals a person’s inclusion into the fabric of the new Canadian society. The common story of ‘being Canadian’ now means how much one subordinates, disowns, or denigrates what was ‘Canadianness’ itself.

In the same sense that the highest purpose of being Christian is not ecumenism, the raison d’être of a nation cannot be to accommodate the outsider or those on the margins.

In today’s multicultural Canada, there is no reward, catharsis, or redemption for the continued sacrifice of the centre to the margins. There is no new greater unity or authentic renewal which has been produced by this transformation, in which Canada becomes less of itself and more of the other.

The end result of any body, in this case the body politic, which fails to renew itself properly, or loses the will to do so, is decomposition, and eventually, death.

Next in this series: Ukrainians and Multiculturalism

One group in particular stood out throughout the history of the North-West, who were largely absent from this post. They would serve as in-between people, and advanced the claim of Canada’s multicultural character throughout the 1960s and 70s.

They were on the periphery of a giant mix of ethnicities and cultures, tucked into the eastern edge of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

A majority came to Canada from the provinces Galicia and Bukovina, and were referred to as several different names in English at the time: from Galicians and Bukovinians, Ruthenians, and eventually, Ukrainians.

Pageau, Matthieu. The Language of Creation: Cosmic Symbolism in Genesis: A Commentary. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, May 2018), 135-36.

Creighton, Donald. Canada's First Century. (MacMillan, Jan. 1 1970), 76.

Urquhart, M. C., editor, and K. A. H. Buckley, assistant editor. Historical Statistics of Canada. (Cambridge: University Press; Toronto: Macmillan Co. of Canada, 1965), 18.

Cited in D.J. Hall, "Clifford Sifton: Immigration and Settlement Policy, 1896-1905," in The Settlement of the West, ed. Howard Palmer (Calgary: University of Calgary Comprint Publishing Company, 1977), 77.

Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan, James Thomas Milton Anderson.

In 1903 and 1906, groups of Presbyterian Assyrians settled near Battleford, Saskatchewan. Led by the Reverend Dr. Isaac Adams, the Assyrians came to Canada to escape religious persecution and were attractive settlers due to their agricultural skills.

Anderson, James Thomas Milton. The Education of the New Canadian: A Treatise on Canada's Greatest Educational Problem. (Toronto: J.M. Dent, 1918), 9.

Pitsula, James M. Keeping Canada British: The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Saskatchewan. (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 77.

"Membership Ku Klux Klan 46,500, He Says: So States Klan Organizer At Meeting Filling Theatre Auditorium Last Night," Regina Morning Leader, July 4, 1927, p. 8.

Ibid.

Waiser, Bill. Saskatchewan: A New History. (Toronto: Fifth House Books, 2018), 74. “Staring around 1905, a handful of black families, attracted by the Canadian advertising campaign in American midwest newspapers, entered the province of Saskatchewan and settled in the Maidstone and Rosetown districts in west-central Saskatchewan.”

"Beginnings And Landmarks: Vanguard Of Barr Colonists," Daily Phoenix, April 10, 1903, p. 1.

Bennett, Richard E. "Canada: From Struggling Seed, the Church Has Risen to Branching Maple," Ensign, (September 1988), 30.

Brunt, P.A. "Laus Imperii." In Roman Imperialism: Readings and Sources, edited by Craige B. Champion. (Wiley-Blackwell 2003), 165.

Ibid. 265.

Holland, Tom. Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. (Basic Books, 2021), 101.