The Encroaching Margins: Ukrainians as Microcosm

Multicultural Symbolism II

Canada is home to the largest Ukrainian population in the world outside of Ukraine and Russia. The first wave of Ukrainian immigrants came to populate the largely undeveloped Canadian North-West at the turn of the twentieth century.

They fit perfectly into the standards set for immigrants by Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton. They were a border-people, subject to various rulers and surrounded by different nations and cultures. They were attuned to a difficult but rewarding life of agriculture, and were slowly losing their land. Canada had ample land and was in need of settlers.

The Ukrainians quickly emerged as a successful and skilled group in their new country. They helped found and develop the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta through their participation in agriculture, education, and other industries.

The Ukrainians also followed in the footsteps of people like the French, Irish, and Métis—acting as an encroaching margin upon the traditional English Canadian centre, contributing to the transformation of Canadian society and culture. Ukrainians were instrumental in the redefining of Canada as a multicultural nation.

The previous post, Multicultural Symbolism I: Settling the North-West explains some of the terminology used here.

The first wave of Ukrainians who came to Canada were mostly from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Austria-Hungary was an extreme and dense precursor of a modern ‘multicultural’ society. At its height, Austria-Hungary had a population of over 50 million, and nearly a dozen ethnic groups, who spoke an equal number of languages. The empire’s borders stretched from Italy in the southwest to Russia in the northeast.

Crossing the Atlantic was only the first leg of the journey for those who left for the Canadian North-West. After arriving at an eastern port, usually Halifax or Montreal, sometimes via the United States through cities like New York, immigrants were shuttled off the boat, and guided onto a cross-country train. Going deep into the interior, some began to have second thoughts about their choice to come to Canada.

The desolate and barren Canadian Shield led some to believe they had been deceived by steamboat merchants or emigration officials.1 It did not look like the fertile and bountiful landscapes on the advertisements, but more like the end of the world.

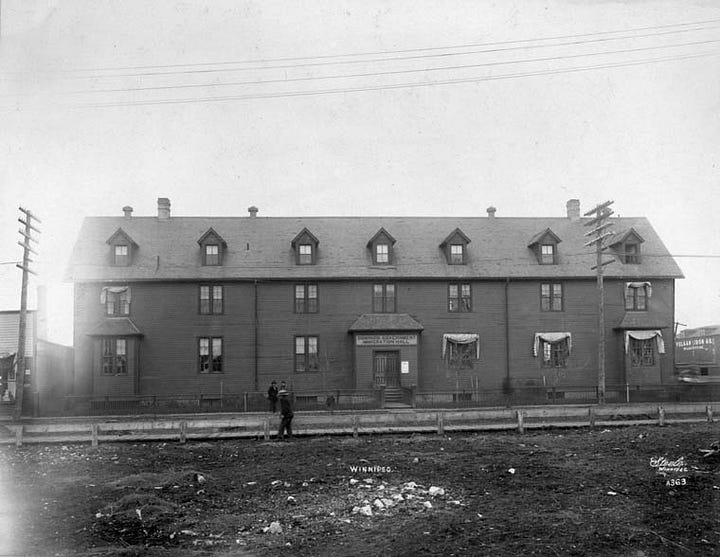

Immigrants were then ushered into Immigration Halls in cities like Winnipeg and Edmonton, until their journey to their final destinations. In the early days of populating the North-West, these Halls were little more than sheds. Larger buildings capable of housing hundreds were constructed later.

In 1897, an immigration official in Winnipeg wrote to his boss about a group of Ukrainians who refused to leave the Halls and go to their places of settlement. He explained how the Ukrainians felt they were enticed in coming to Canada with false promises:

They were told that the Crown Princess of Austria was in Montreal, and that she would see that they got free lands with houses on them, cattle and so forth, and that all they [were] required to do was to telegraph her in Montreal in case their requests were not granted. These and other similar stories have been so impressed on their minds that they now seem very unsettled, and talk about going back to Austria. Well God knows we should be glad to get rid of them, but what effect would it have on future immigration from that country? I fear that it might prevent others coming who had some means.2

The same official describes his patience wearing thin for the Ukrainians’ plight:

A more ignorant, obstinate, unmanageable class, one could not imagine… There is no doubt about it, a certain amount of force has got to be used with this class as they will not listen to reason, and the more you do for them, the more they expect… Both men and women once or twice a day set up a blubbering match, worse than any Irish wake, and our relations are about as strained and difficult to fathom as those existing at present between the Greeks and Turks.3

Likely neither party in the dispute left a favourable impression on each other. After a few days, with the assistance of the police, and continued explanations of the reality of the situation by interpreters and officials, this group of Ukrainians boarded trains to their final destinations.

Faith Between Worlds

It is unlikely that immigration officials had the Schism of 1054 on their mind when populating the North-West. But this event one thousand years in the past still had relevance for the Ukrainians. As an in-between people, long-standing divisions between east and west impact daily life—including this breaking of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.

A majority of Ukrainians who came to Canada from the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia were Eastern Catholics, belonging to what is known today as the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.4 Most Ukrainians have been Eastern Catholics since 1596, when the Union of Brest agreement between Ruthenian bishops (Ruthenian referring to lands which overlap with modern Ukraine) reunited their churches with the Roman Catholic Church.

The agreement saw the Ruthenian bishops transfer their ecclesiastical jurisdiction from Constantinople to the Holy See of Rome.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is one of 23 autonomous Eastern Catholic particular (meaning “of its own law”) churches, which are in full communion with the Pope, but retain many of the forms of the liturgy, language, and traditions common to Orthodoxy.

In an in-between position, Eastern Catholics accept the supreme authority of the Pope, but they are not direct subjects of his authority in their organizational structure.

The Ukrainians came to Canada with no clergy of their own, due to a Vatican decree which did not allow married priests to come to the New World.5 They were also accustomed to a liturgy in the language of Old Church Slavonic, but were now under the care of a largely French-Canadian Latin clergy. Attempts by the Church to accommodate the Ukrainians in Canada initially fell flat.

The appointment of Polish, Latin rite priests brought back Old World concerns about the abuses the Ukrainians suffered at the hands of the Polish nobility; the large estate owners in Galicia who dictated much of their economic activity, and who historically played a hand in attempts to ‘Latinize’ Ukrainian religious practices.6

Archbishop Adélard Langevin of St. Boniface (Winnipeg) was the key figure of the Catholic Church in the Canadian North-West at this time. Langevin wrote to the Redemptorists, a missionary group, in search of additional priests for Ukrainian immigrants. Langevin shows his contempt for the Ukrainians, as they refused to defer to the supposed superiority of the Latin rite and hierarchy:

The best would be to leave Latin-rite religious [to] take care of these people. For centuries these unhappy races have been given over to wavering in their faith and to betraying Grace. Bastardized and ignorant races, unable to profit from the freedom of this country. They passionately tie themselves to the rite--to exterior practises--in inverse proportion to any serious belief. Our religious missionaries are a revelation to them. One Latin priest like one of your Redemptorists, an Oblate, an Assumptionist, is worth ten of their priests! So, let us save as many as we can and the rest will go to Hell.7

Unsurprisingly, Langevin’s point of view was poorly received by Ukrainians. Without their own clergy, some Ukrainians went over to the Orthodox Church of their countrymen, or were enticed to join different Protestant denominations.

Sticking to the form and rituals of the old country was unacceptable to someone like Langevin, who sought to enforce the orthodoxy of his world. As a French-Canadian Catholic on the prairies, his people were already outnumbered. Langevin believed anything which further fractured Catholics would accelerate their marginalization, and absorption into the dominant English and Protestant culture.

In symbolic terms, Langevin was trying to remove gradation. By bringing the Ukrainians in line with the common Latin rite, he hoped to stabilize Catholic identity in the Canadian North-West.

Matthieu Pageau explains this process of removing gradation:

In ancient cosmology there were also important relationships between the concepts of change and continuity as well as stability and discontinuity… maximum instability is achieved by inserting infinitely many intermediate states between opposites, and maximum stability is achieved by removing all intermediate states.8

Langevin viewed Ukrainian Catholics as an intermediate state, who were causing confusion and discontinuity in the Church—residing outside of the organizational and liturgical ‘norms’.

But, Langevin realized that the tide of immigration was not going to stop anytime soon, and it wasn’t just Ukrainians. By 1916, immigrants with German as their mother tongue already outnumbered the French-Canadians in the prairie provinces—by almost two to one.9 Leaving the quickly growing Ukrainian laity to organize themselves could be more detrimental to the faith than their adherence to their Eastern traditions.

The Ukrainians continued to petition for own priests, and in 1900, Langevin made arrangements to recruit unmarried Ukrainian clergymen.10 By 1912, the Ukrainians had their first bishop in Canada, Nykyta Budka.

The Ukrainians went up against an entrenched institution of one of the founding peoples of Canada, and prevailed. The Ukrainians managed to carve out a unique accommodation which allowed them to retain a key aspect of their identity, resisting a transformation of their religious life.

Working between the margins and the centre in this way contributed to the Ukrainian status as an in-between people in Canadian society. They walked a line of not fully embracing or sacrificing themselves in the process of ‘becoming Canadian’, when it came to their religion and language, yet they staked a legitimate claim of belonging—as a founding people of the prairies.

Competing Loyalties

In 1914, the Ukrainian in-between position in Canada had major consequences with the outbreak of war in Europe. Canada and Austria-Hungary were on opposing sides of the conflict. Canada also came into its own as a nation during the First World War. Recent immigrants suddenly had both their homeland and their adopted country demanding their loyalty.

Bishop Budka became embroiled in controversy on the eve of the war. Historian Stella Hyrniuk describes the affair:

At a time when war on the European continent seemed imminent but when no country was yet at war and very few Canadians thought that the British Empire would be involved – Budka issued a Pastoral Letter in which he urged Ukrainians who still had military reservist obligations in Austria to return home: “Perhaps we will have to defend Galicia from seizure by Russia with its appetite for Ruthenians ...” The Letter, though well meaning, was no doubt naive. By 4 August Britain was also at war, and on the same side as Russia. Budka immediately issued another Pastoral Letter, dated 6 August, in which he explained the changed situation, urged that his 27 July Letter be disregarded, and exhorted everyone to perform his duty to Canada. The damage had nevertheless been done.11

Bishop Budka’s initial hastiness confirmed the suspicions harboured by many Canadians towards recent immigrants—that their true loyalties lied elsewhere.

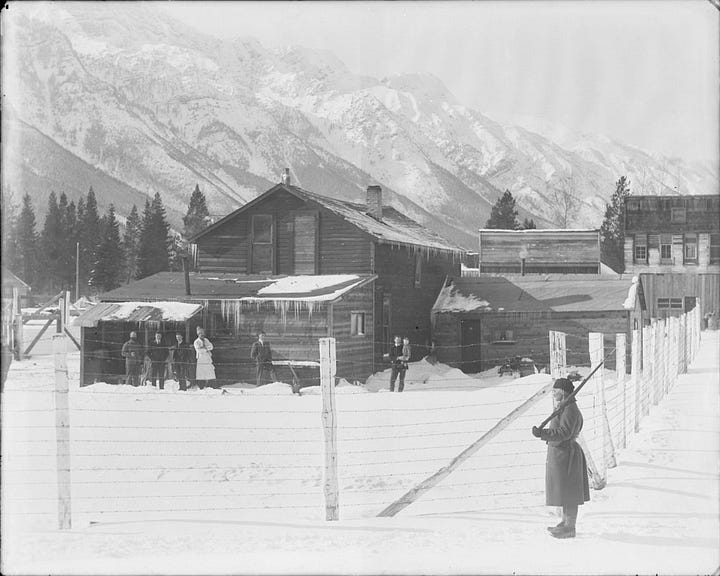

War was a time of unity, when the margins would need to be identified and controlled, to remove gradation and stabilize Canadian identity. Ukrainians were well represented among the over 8,000 people held at 24 internment camps across Canada during the war.12

Those of German or Austro-Hungarian nationality could be held in these detention centres if there were reasonable grounds to believe they were attempting to engage in acts of espionage, assisting the enemy, or it had proven that they had already done these acts.

Even those not interned were liable to be viewed as an enemy and outsider. Around 80,000 people, mostly Ukrainian-Canadians, were registered as ‘enemy aliens’ during the war.13

These attacks on the Ukrainian community from the outside were also accompanied by an internal fracturing of Ukrainian life in Canada. There was a small but vocal group of professionals and students which could be referred to as an ‘intelligentsia’, who emerged as leaders of a developing Ukrainian secular culture following the war. Anti-clerical attitudes, secularism, and Ukrainian nationalism were all common beliefs of this group.

These parallel secular institutions threatened the authority of the Church, and tensions between them and Bishop Budka came to a head:

The conflict had developed to a point where no compromise was possible and none was offered. Bishop Budka was adamant in his stand against secular institutions… those members of the intelligentsia who were Greek Catholic communicants realized their insistence of the secularization of education was fundamentally incompatible with the aims and character of the Church… If the intelligentsia was truly interested in paying more than lip service to Christianity, it had to seek refuge in another denomination.14

A group of young Ukrainian anti-clerical professionals, mostly teachers, took the initiative to push the issue of breaking up the Ukrainian Church entirely from Latin influences. It was partly because of these tensions that a separate church was formed in 1918, the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada.

A majority of Ukrainians in Canada remained of the Greek Catholic rite, but the split was another sign that adjustment to their new homes would lead to sacrifice and fracturing of their identity.

Ukrainians in Canada also watched the institutions and culture of their homeland be altered or wither away under communist rule. A second wave of Ukrainian immigration into Canada occurred in the 1920s and 30s occurred partly because of this.

The Soviet Union banned the Autocephalous Orthodox Church in 1930, and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in 1946. The 1932-33 man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine, known as the Holodomor, produced long-lasting, visceral antipathy amongst many Ukrainians, towards communism and the Soviet state. At the lowest estimates, 3.5 million Ukrainians died as a result of the famine.

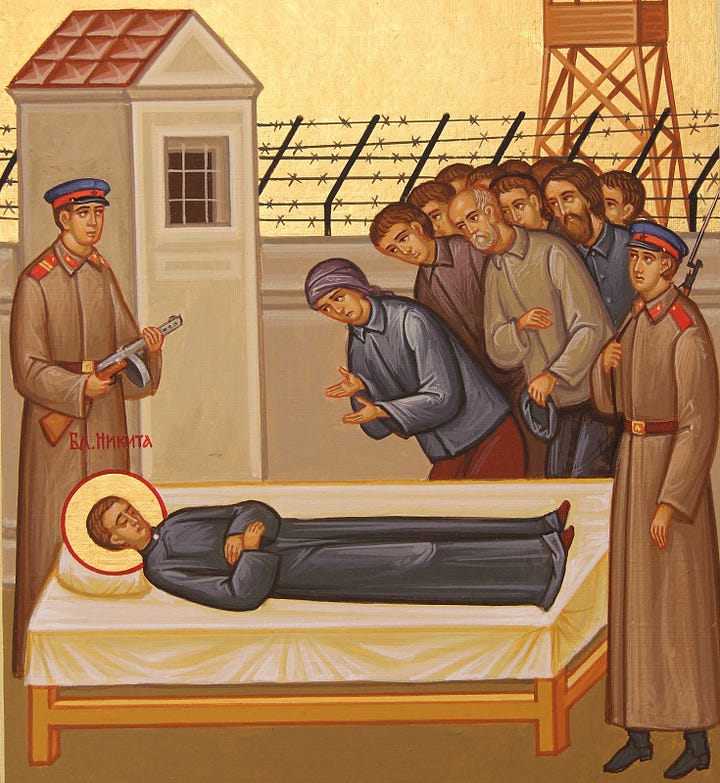

Bishop Nykyta Budka himself was a victim of Soviet persecution. In 1928, Budka resigned as Bishop in Canada and returned to Galicia. In 1945, he was caught up in the repression of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and imprisoned. Budka died in a labour camp in 1949. In 2001, he was beatified and declared a Blessed Martyr by Pope John Paul II.

Efforts were made to solidify Ukrainian identity in Canada partly in response to these troubles in their homeland. The Ukrainian Canadian Congress was established in 1940 as a national organization to lead, coordinate, and represent Ukrainian-Canadian interests under one umbrella. And institutes and centres for Ukrainian studies were created at universities across the country.

Entering the latter half of the twentieth century, the Ukrainians established themselves as founding people of the prairies. They survived schism, persecution, and the hardships of pioneer life. Sometimes in a single generation, families moved from illiterate peasants to having their children enrolled in school, learning English, attending university, owning businesses, and fighting in war for their new nation.

The Third Element Or: The Coalition of the Margins

In the 1960s, Canada was well underway redefining itself a nation. A new sense of what ‘being Canadian’ is, was forming. Some Ukrainians led this transformation. They took their microcosmic experiences in sacrificing parts of their identity in adapting to their new homes, and made this process an equally valid component of the macrocosm, or what it means to ‘be Canadian’.

Paul Yuzyk was among the most prominent Canadians of Ukrainian descent involved in the multicultural project, which sought to redefine Canadian identity as a mosaic—a collection of various cultures and peoples, whose contributions to the nation should be valued no less than those of the British or French.

Yuzyk has often been referred to as ‘The Father of Multiculturalism’. Yuzyk brought the ideas of multiculturalism into their full expression in the wider Canadian consciousness in his role as an intellectual, activist, and Senator.

Yuzyk was born in 1913, near Estevan, Saskatchewan; his parents were a part of the first wave of Ukrainian immigration from Galicia. Yuzyk was a teacher for several years, and later earned a PhD. He was a Professor of History and Slavic Studies from 1951-63 at the University of Manitoba.

As an historian, Yuzyk understood the value of being embedded in a story. Yuzyk became a vocal leader in the Ukrainian community of Winnipeg, and Canada at large, as he involved himself in several boards, clubs, and organizations, and supported initiatives and projects which continued to foster a unique Ukrainian-Canadian identity and culture.

Yuzyk’s profile as a scholar and activist grew to a point of national recognition by the early 1960s. In 1963, he was appointed to the Senate by a fellow prairie boy, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Yuzyk was poised to share and embody the story of the Ukrainians in Canada on the national stage. His maiden speech to the Senate was delivered on March 3, 1964, entitled ‘Canada: A Multicultural Nation.’

Yuzyk divided the major ethnic groups in Canada into three elements, rather than two. The first two he acknowledged were the British and French, with the third being all others. Yuzyk declared that “Present-day Canada [1964] is a country of minorities, and this fact should not be ignored.”15 Yuzyk called the third group the ‘third element’. He elaborated on the role in Canada of the ‘third element’ as being similar to that of French-Canadians:

The joint contribution of the various ethnic groups of the Third Element to the Canadian way of life is like that of the French, in the cultural sphere with political and constitutional implications. By their perpetuation of the best of their cultural heritages, these groups have made Canadians more conscious of cultural values, out of which there has emerged the principles of “unity in diversity”, or, stated in another way, “unity with variety”, as a rule of governance.16

Yuzyk also framed his vision of ‘being Canadian’ in familiar terms: in opposition to the ways of the United States, “the three elements side by side in our society provide sound materials for the building of a strong Canadian nation… a pattern which has been developing in a different way from that of our neighbours to the south.”17

Yuzyk continued to advocate for a vision beyond the British and French dichotomy. He had an important ally in this—a fellow Ukrainian and his former professor, J.B. Rudnyckyj. Rudnyckyj was an renowned linguist who spoke Ukrainian as well as English and French. Rudnyckyj founded the Department of Slavic Studies at the University of Manitoba.

Rudnyckyj was a member of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. The Commission was established by Prime Minister Lester Pearson in 1963. It was created in response to growing tensions in Quebec regarding their language, culture, and political rights in relation to the rest of Canada.

Rudnyckyj shared many of Yuzyk’s beliefs about the oversight of the commission in addressing contributions of the ‘third element’.

Rudnyckyj used his position to advocate for the ‘third element’ to be prominently included in the final report, which influenced a future policy of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Trudeau discarded the bicultural view of Canada, and replaced it with a policy of ‘multiculturalism within a bilingual framework’. 18

Is Multiculturalism a Christian Ethos?

There are symbolic parallels which can be drawn out from rejection of the traditional British and French dichotomy, and the elevation of the ‘third element’—which set the course for Canada officially becoming a multicultural nation.

Christ’s parables often use an everyday situation embodied in history, to bring out underlying cosmic truths about how reality unfolds.

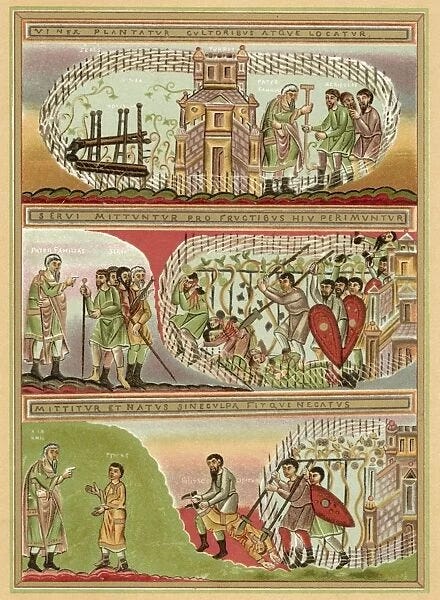

One theme of the Parable of the Wicked Vinedressers is the rejection of inheritance, and the attempt to take the fruits of an established order for oneself.19

In this particular story, Christ describes a vineyard, which consists of a winepress, tower, and a hedged perimeter. These basic components serve as a microcosm of an established order, with clear boundaries and purposes, which, when working properly and in concert, produce fruit.

The Kingdom of Heaven is the established order which Christ is pointing to in this story. We are called to participate in this inheritance, whose vines descend to fill our lives with meaning, order, and spiritual fruit.

Christ begins the story, saying that the owner of the vineyard went away, leaving vinedressers to tend to his property. The owner trusts that the vinedressers will carry on the established order and ensure that fruit continues to be produced.

The owner then sends servants to collect the fruit from the vinedressers so it can be made into wine. But the vinedressers kill the servants. Finally, the owner sends his son to collect the fruits, believing the vinedressers would respect him.

The Book of Matthew continues:

38 But when the vinedressers saw the son, they said among themselves, ‘This is the heir. Come, let us kill him and seize his inheritance.’ 39 So they took him and cast him out of the vineyard and killed him. (Matthew 21:38-39)

In killing the owner’s son, the vinedressers destroyed the functioning of the vineyard all together. They had disrupted things enough that now no fruit would be produced—the owner would find new land or lease it to someone else, and the vinedressers would eventually be punished.

Christ told this parable to a group of Pharisees, who rightly understood that He was talking about them, and their rejection of Him. The Father had sent servants (prophets, holy men) who were rejected or killed, and now Christ (the Son) had been sent by the Father.

Christ is both the inheritor and progenitor of the established order. He tells the Pharisees that in their rejection of Him, He who binds all things together, they would be denying themselves spiritual fruit; and as a consequence, meaning and order would be taken from them:

43 Therefore I say to you, the kingdom of God will be taken from you and given to a nation bearing the fruits of it. 44 And whoever falls on this stone will be broken; but on whomever it falls, it will grind him to powder. (Matthew 21:43-44)

The early proponents of multiculturalism in Canada rejected the roots and inheritance of Canadian identity—while believing they could preserve an ordered and functioning culture and society.

In the 1960s and 70s, the inclusion of the ‘third element’ into the story of what it meant to ‘be Canadian’ did not require tearing down the existing order of the country’s identity entirely. But this inclusion did help further reassessments about Canada’s character and peoples, which would ultimately cause disorder and confusion.

The work of Yuzyk, Rudnyckyj, and others showed that the inheritance of the centre was not as solid as it appeared, and the authority which binds Canadians together could be taken and given to others.

It is symbolically appropriate that an in-between people like the Ukrainians would contribute to a transformation in this fashion; spurring a transitory alteration and redefinition, which would set the stage for further changes down the line.

Senator Yuzyk, and many of the men who reshaped Canada in the twentieth century, took for granted that some positive attributes of Canada were self-evident, and would never come into question. Yuzyk ended a speech in the Senate with some unimpeachable truths about Canada:

Fundamentally, we are a Christian and democratic nation. Let us not forget that all men are born in the image of God. Believing in the Fatherhood of God, we also believe in the brotherhood of man and the brotherhood of peoples and nations… Let us look to Canada’s future with the faith of our Founding Fathers, of our pioneers of various origins, and of our great leaders.20

Yuzyk would be heralded as a father of a set of ideas in Canada which would not spare the religious and historical inheritances he valued.

Yuzyk’s funeral and gravestone exemplified his life’s work, and in-between position in Canadian society. His funeral took place in 1986 at Ottawa’s grand French Catholic Notre Dame Cathedral, with Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk, head of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Canada as the main celebrant.

Yuzyk identified the ethos and aims of multiculturalism as compatible and informed by Christianity. Most early proponents of multiculturalism viewed these ideas as a simple extension of their faith.

There are similar problems which Christianity and multiculturalism try to address regarding multiplicity and unity. Both involve sacrifice and negation of identity. But Christianity and multiculturalism deviate in what they ultimately aim towards.

When ordered to the highest good—towards God—Christian values sort themselves into a hierarchy which informs their intent and practice. For example, when we carefully focus on and contemplate the Trinity, we see a unity achieved through diversity, and reconciliation between the one and the many.

Inclusion, tolerance, and diversity are good—to the extent they participate in the highest good, and are reflections of it. Placing them as ultimate, guiding values themselves has only focused more attention on our differences, and has not bound us together.

Symbolic Current Events

In 2023, an event in the House of Commons highlighted the in-between position of Ukrainians in Canada today. As a part of the visit of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a 98 year old Ukrainian veteran of the Second World War, Jaroslav Hunka, was honoured and given a standing ovation in Parliament.

Speaker of the House Anthony Rota explained how Hunka fought for Ukrainian independence against the Russians, and he continued to support the Ukrainian troops doing the same today.

During the Second World War, many Ukrainians supported and fought with militia and military groups caught between Hitler and Stalin’s regimes. With their ultimate aim to create an independent Ukrainian state.

Only after Hunka was honoured in Parliament, did it come to light that he fought with the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician). The same unit was also called the 1st Division of the Ukrainian National Army. In other words, the House had applauded him for fighting for Nazi Germany.

In the rush to support a nationalist sentiment allowed to be expressed in Canada—one which is not of the traditional centre—considerations of history were swept aside, and this embarrassing episode resulted. Speaker Anthony Rota took the fall and resigned over the incident.

Today, Ukrainian-Canadians still have a sort of in-between position amongst the centre and the margins. But the margins of yesterday are not the margins of today in Canada. As the country has been opened to mass immigration from all over the world, gradation between Canadians of European descent has been removed, and the Ukrainians have ‘become Canadian’.

Next in this series: The Centre Recedes: Multicultural Symbolism III. We will see how the Canadian centre reacted to these impositions from the margins, and look into changes to Canada’s symbols and markers of identity in the 1960s and 70s.

This is a condensed chapter from an upcoming book by Mitch Sherven, on Canadian history and religious symbolism. Check out Mitch’s published work here.

Petryshyn, Jaroslav. Peasants in the Promised Land: Canada and the Ukrainians. (Lorimer: First Edition Jan, 1985), 61.

Ibid.

Martynow, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton 1991), 4.

By October of 1890, Propaganda Fide asked that all married and even widowed clergy be recalled.

Pospishil, Victor J. Ex Occidente Lex – From the West, the Law: the Eastern Catholic Churches under the Tutelage of the Holy See of Rome (Carteret, NJ: St. Mary’s Religious Action Fund, 1979), 24.

Petryshyn, Jaroslav. Peasants in the Promised Land. 130.

Quoted in Paul Laverdure. Achille Delaere and the Origins of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Western Canada. 100. From Historical Papers 2004: Canadian Society of Church History.

Pageau, Matthieu. The Language of Creation: Cosmic Symbolism in Genesis: A Commentary. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, May 2018), 137.

Taken from the 1916 Census of the Prairie Provinces. Page Xxxv. German-speakers outnumbered the French 101,944 to 59,093.

Yuzyk, Paul. The Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada, 1918-1951. (University of Ottawa Press, 1981), 44.

Hyrniuk, Stella. Pioneer Bishop, Pioneer Times: Nykyta Budka in Canada. (CCHA Historical Studies 55, 1988), 34.

Roy, Patricia E. Internment in Canada. (The Canadian Encylopedia)

Ibid.

Yuzyk, Paul. The Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada. 77.

Yuzyk, Paul. For A Better Canada. (Ukrainian Echo, Publishing Co. Ltd.), 26.

Ibid, 37-38.

Ibid.

Prymak, Thomas M. J.B. Rudnyckyj and Canada. (University of Toronto, March 2019).

Pageau, Jonathan. Christianity is Not Revolutionary: Parables of the Vinedressers and the Wedding Feast. (YouTube)

Yuzyk, Paul. For A Better Canada. 48.