In the previous post, we looked at the Ukrainians in Canada—a group from the margins who helped change Canadian identity from predominantly British and French to ‘multicultural’. Now we will look at a small group of leaders from the centre who contributed to this process.

The first post in this series explains some of the terminology used here.

In the 1960s and 70s, Canada went from being embedded in a story, a people in a shared community, nation, and empire, to an orphan or a widow—disconnected from a hierarchy, and without the principles that once unified us. The traditional sources of meaning and purpose were dismantled and put aside.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau is often given the credit, or blame, depending on the view, for Canada becoming ‘officially’ multicultural in the 1960s and 70s. As Prime Minister from 1968-79, and again from 1980-84, Trudeau was arguably the most important figure in instantiating multiculturalism into the public consciousness. But the foundations were already in place by the time Trudeau came into power.

Before Trudeau, Canada was set down a path of transformation, becoming “less of itself and more of the other”1 as English Canada broke away from Britain, French Canada secularized, and changes were made to the country’s international image, national symbols, and immigration policy.

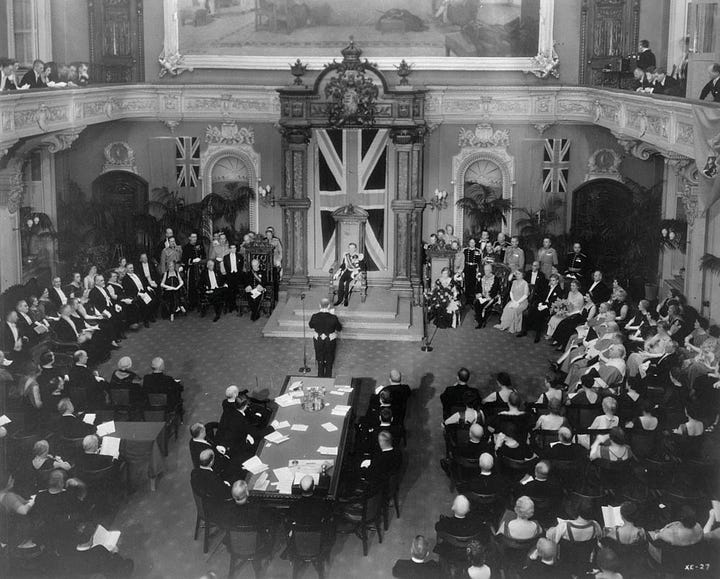

Imperial Progress

Historian Peter Henshaw highlights the role of John Buchan, later known as Lord Tweedsmuir, Governor General of Canada from 1935-40, as an early supporter and proponent of multiculturalism in Canada.2 By all appearances, Buchan embodied the traditional Canadian centre, as a direct representative of the crown.

In broad symbolic terms, the notion of the centre is that which is orderly, authoritative, safe, clearly defined, orthodox, traditional, or static. The margins are that which is chaotic, leftover, concealed, strange, dangerous, enticing, or foreign.

Buchan was accustomed to the mixing of cultures and identities in an imperial context. Buchan’s beliefs were shaped in part by his experiences on the margins of the Empire, in the South African civil service—as he mended disputes between English and Boer settlers.

Later, as Canada’s Governor General, Buchan felt it was his duty to travel Canada extensively to meet and celebrate the country’s unique mix of peoples.

In 1938, John Murray Gibbon wrote Canadian Mosaic: The Making Of A Northern Nation, which helped to popularize the use of the term ‘mosaic’ to describe the increasingly diverse makeup of peoples in Canada.3 In the book, Gibbon quotes Governor General Buchan’s 1936 speech to a group of Ukrainian-Canadians in Fraserwood, Manitoba. Buchan drew similarities between them and the experience of Scottish emigrants:

I wish to say one thing to you. You have accepted the duties and loyalties as you have acquired the privileges of Canadian citizens, but I want you also to remember your old Ukrainian traditions… We Scots are supposed to be good citizens of new countries, that is largely because, while we mix well with others and gladly accept new loyalties, we never forget our ancient Scots ways, but always remember the little country from which we sprang. That is true of every race with a strong tradition behind it, and it must be so with a people with such a strong tradition as yours. You will all be better Canadians for being also good Ukrainians.4

Buchan certainly appears to be an early proponent of multiculturalism in Canada. But Peter Henshaw also makes note of the limited scope of Buchan’s beliefs. The Governor General was greatly restrained compared to later proponents of multiculturalism:

Buchan certainly made no secret of his admiration for “northern” races, by which he meant people from northern Europe. As a devout Christian, he also privileged his religion. And although he never explicitly admitted as much, it would be safe to surmise that he preferred Canada to be populated predominantly by Christians of northern European descent. But it would be easy to make too much of his preference. His vision of Canada did not depend on people of British descent remaining the majority there.5

For men like Buchan, of the centre, his values were still nested in an explicitly Christian tradition, and always with the betterment of the Empire in mind. If it served British interests to allow a degree of cultural pluralism in its distant dominions, that could be tolerated—and even promoted.

Much like Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior who brought the Ukrainians to the prairies, many of the elite in English Canada were making what they believed to be short-term sacrifices. Traditional conformity and cohesion could be temporarily weakened, if that ultimately contributed to long-term imperial unity and growth. But within a few decades, Canada’s ties to the Empire were breaking apart.

Entering the latter half of the twentieth century, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King oversaw a gradual cultural and economic shifting away from Britain to the United States. Developing a distinct Canadian national identity to contend with American influence proved difficult.

By 1947, Canadians were also no longer British subjects. The Canadian Citizenship Act created a separate Canadian citizenship. Under Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, in office from 1948-57, there were more strides taken to separate from Britain.

St. Laurent, Canada’s second francophone Prime Minister, put Canada on a positive post-war footing as the country looked for an independent identity. St. Laurent’s cautious and moderate approach lent itself well to economic development and stability.

In 1949, there was a strengthening of national sentiment when Newfoundland was brought into Confederation, as Canada’s tenth province. In the same year, an amendment to the Supreme Court Act transferred jurisdiction from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain to the Supreme Court of Canada. This gave Canada its own highest court of appeal.

Also in 1949, the establishment of NATO brought Canada and the United States closer together.

Both King and St. Laurent had a focus on establishing Canadian sovereignty separate from Britain, but they often took half-measures and cautious steps towards these aims. St. Laurent introduced subtle yet enduring changes which furthered the divide between Britain and Canada.

In 1952, St. Laurent appointed Vincent Massey as the first Canadian-born Governor General. Massey was influential in promoting the arts in Canada. Massey was the head of the 1949 Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, which investigated the overall state of culture in Canada.

Massey called for more involvement from the centre in developing a unique Canadian artistic identity. Massey’s report after the commission led to the creation of grant-giving agencies within the federal government, such as the Canada Council for the Arts, and the establishment of the National Library of Canada.

In the quest to foster an independent national identity, historian Donald Creighton notes that Canada itself was quietly renamed by the Liberal Party establishment of the 1950s:

In the change of national nomenclature, King and St. Laurent showed a determined, but surreptitious, and even secretive, persistence… the word ‘Dominion’, in the eyes of doctrinaire Liberal nationalists, had sunk into unfashionable disrepute. No statute or order in council authorizing a change of title was ever passed; and no frank statement of government policy was ever issued. Quietly, unostentatiously, the word ‘Dominion’ was simply dropped, at every opportunity, from public documents; and the ‘Dominion of Canada’ became ‘Canada’ or ‘the Government of Canada.’6

By the 1950s, in official and legal terms, Canada appeared to no longer be a colony. But the post-war order simply saw the United States usurp Britain’s role in Canada’s politics and culture. This extended to Canada’s participation in world events.

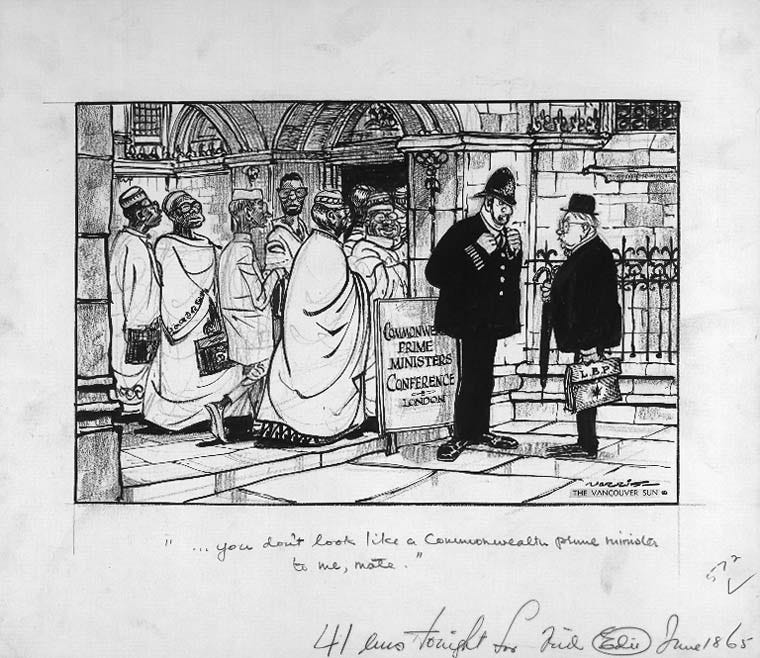

Global Citizens

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, in office from 1963-68, was involved in shifting Canada’s foreign policy and standing on the international stage. Pearson first gained notoriety as Secretary of External Affairs under Prime Minister St. Laurent. In 1957, Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in employing an international United Nations peacekeeping force during the Suez Crisis; the event in which Britain and France, along with Israel, attempted to retake control of the Suez Canal and remove Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser from power.

Pearson was awarded for his efforts, but pressure from Washington was likely the deciding factor in causing a withdrawal of western forces from the conflict. Pearson fulfilled the vision of men like Mackenzie King in raising Canada’s international profile.

Pearson was able to navigate the post-war liberal order. He played an active part in the technocratic, consensus-making machinery of the United Nations, serving as a liaison between the old and new powers in world affairs. Pearson also established Canada’s reputation as ‘peacekeepers’—an in-between role which persists to this day.

The Suez Crisis is often viewed as a major blow to Britain’s status at the forefront of international relations, while further decolonization and the rise of the United States furthered this trend.

There were differences of opinion in how Canada should look heading into a new era. This can be seen in differing views on immigration. In the 1940s, Prime Minister Mackenzie King fully believed in the importance of Canada being perceived as a bastion of post-war liberalism. But King did not believe in altering the ethnic makeup of the Canadian people in order to prove a commitment to equality or diversity.

In 1947, King defended his immigration policy which still drew primarily from northwest Europe:

With regard to the selection of immigrants, much has been said about discrimination. I wish to make quite clear that Canada is perfectly within her rights in selecting the persons whom we regard as desirable future citizens. It is not a “fundamental human right” of any alien to enter Canada. It is a privilege. It is a matter of domestic policy…There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that the people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population.7

Even though leaders like King still held onto these beliefs, some members of the traditional centre were thinking differently about immigrants and their role in Canada.

Lee Blanding in his 2013 dissertation is of the view that the practice of ‘multiculturalism’ in the federal civil service was present as early as the 1950s, just after King retired. Blanding examined the activities of the ‘Canadian Citizenship Branch’, who “had direct control over and interest in the way that immigrants, ethnic minority communities, and even Indigenous Peoples fit into Canadian society” and “looked after the public perception and reception of minority communities — what was then known as ‘integration.’”8

Blanding argues that the federal bureaucracy had long accepted the views later associated with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, who instituted multiculturalism as policy:

[Trudeau’s] multiculturalism policy of 1971 did not amount to a fundamental change in the way that the Canadian state perceived and dealt with ethnicity, but was, rather, a public acknowledgement of both a philosophy and set of social programs that had been built over a couple of decades.9

Prime Minister Pearson had also done his best to affect change before Trudeau. Pearson’s concern for the international order, and Canada’s place within it, demanded changes to the nation’s character, to bring Canada in line with post-war liberal ideals.

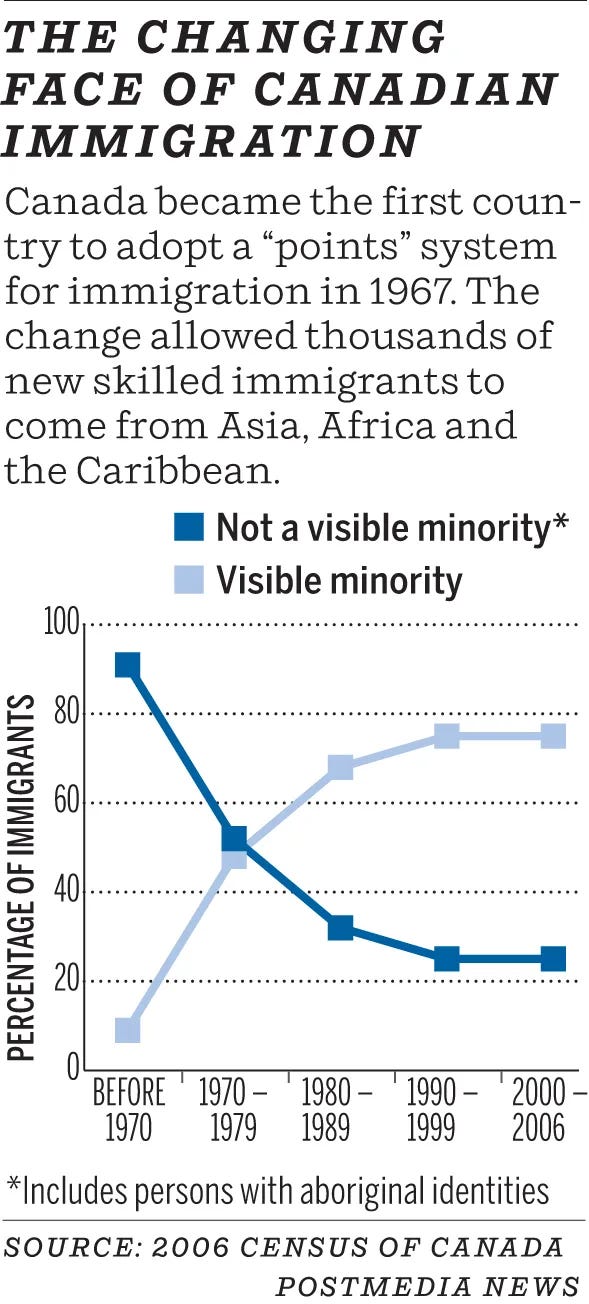

In 1967, under Pearson, Canada switched to a points-based immigration system, introducing a transformation to the ethnic makeup of the country. The new system favoured immigrants based on their levels of education, language proficiency, age, occupation, etc. rather than primarily taking into account their country of origin.

One writer describes the political benefits of the decision, “[The points system] offered Canadian politicians a way of demonstrating the purity of Canada’s intentions to the rest of the world. Immigration had been placed on a progressive footing, in line with the image Canadian officials wished to project both domestically and internationally.”10

From King, to St. Laurent, Pearson, and then Trudeau, the Liberal Party slowly reshaped the international reputation and internal character of the nation, guiding Canada down a path of becoming ‘multicultural’.

The Centre Reorganizes

As Prime Minister Pearson changed the type of immigrant coming into the country, he also had to contend with challenges to Canadian identity from within. In the 1960s, Quebec was undergoing its ‘Quiet Revolution’. In only a single generation, the most Catholic place outside of Vatican City underwent a rapid exodus from religious life.

In Quebec, the meaning, purpose, sense of community, and rhythm to life once occupied by the Church had been eroded. This hole was filled by a nationalist movement. Without the Church to bind them together, French-Canadians turned to their language and secular culture to unite themselves. This led to calls for separation from English Canada entirely.

In 1963, largely in response to the Quiet Revolution, Pearson appointed the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism.11 Historian C.P. Champion in his book The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism, 1964-68, covers the steps taken by Pearson and others in leadership during this time to change Canada’s identity and symbols.

Champion argues that these officials actually perpetuated the traditions and ethos of the centre, in a very Canadian way—through hybridity:

The country that emerged from the crisis of Britishness at the end of the 1960s as an officially bilingual, increasingly multicultural liberal state, was the natural hybrid successor to a multiracial Empire, a fulfillment, and not a rejection, of British imperialism.12

Historian Michael Gauvreau makes a similar argument in his book The Catholic Origins of Quebec's Quiet Revolution, 1931-1970—that the Quiet Revolution occurred with greater input from the French-Canadian centre than many realize. Along with fringe groups like the FLQ13, it was groups within the Church itself, the traditional centre of French-Canadian society, that played a large role in instituting change.

In the 1960s, the English and French both attempted to transform their institutions and symbols which they had used to define themselves, and had also bound the two peoples together, however tediously. New national symbols were created in an attempt to lay down new ties to bind the two Canadas together.

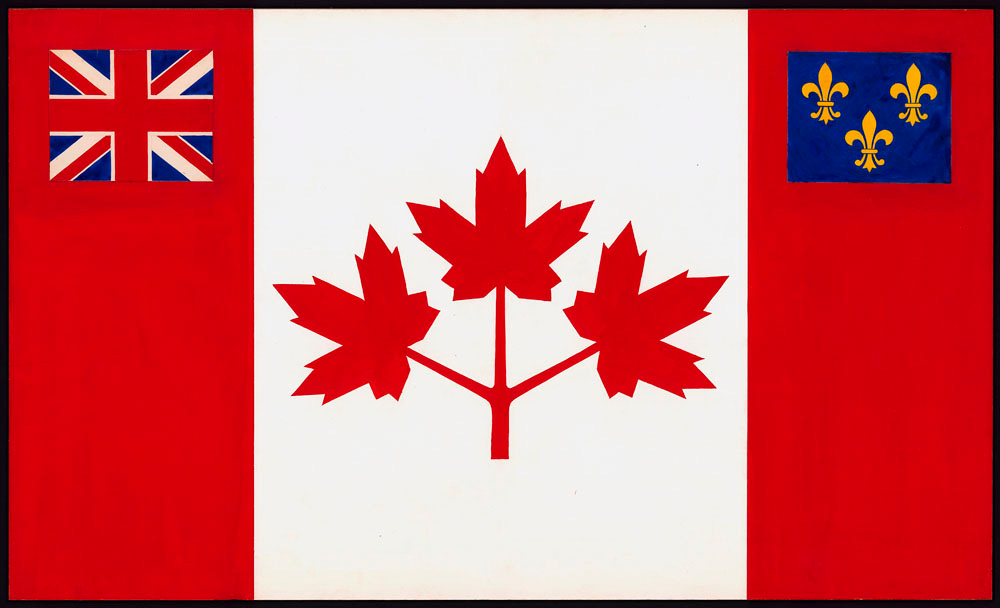

The most prominent new national symbol was created during Pearson’s tenure as Prime Minister: the Maple Leaf flag.

Farewell the Trumpets

The flag which was to be replaced by the Maple Leaf—the Canadian Red Ensign—had never officially been designated as the national flag. But it was widely recognized as Canada’s flag from the late 1800s until 1965, and used interchangeably with the Union Jack, which was flown officially. Prime Minister Mackenzie King had formed parliamentary committees in the 1940s to design a new flag, but the project was abandoned.

The Red Ensign or the “Red Duster” is the flag flown by British merchant or passenger ships since 1707. Several overseas British territories used the design on their flags.

Red Ensigns throughout Canada’s history

In 1963, a series of lengthy and ugly parliamentary debates began to design a new flag. Some in English Canada viewed the entire project as a concession to Quebec—which wasn’t far from the truth.

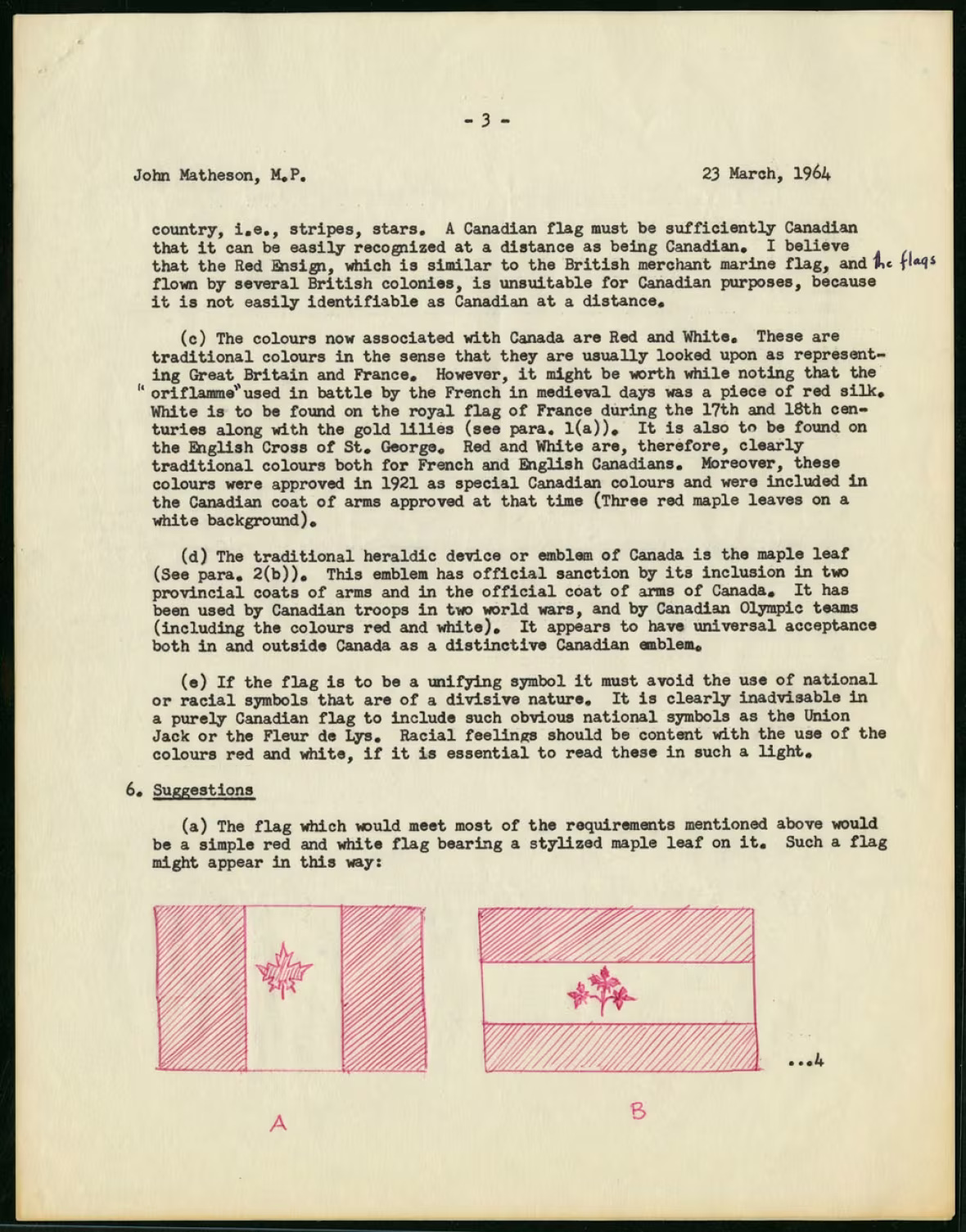

John Ross Matheson, a Liberal member of the parliamentary committee to design the new flag, explains his view of Pearson’s motivations:

Canada needed a man with that brand of special courage to defuse violence, reconcile differences and substitute coherence for incoherence in Canadian politics… Recognizing conciliation not as cowardice but as wisdom, Pearson entered upon his great term as leader. He believed compassion and understanding were vital to check the disposition towards rebellion. He was determined to do his utmost to save the Confederation. His policy of promoting a distinctive flag for Canada was fundamental to his purpose of reconciling French Canada to the Canadian union.14

Beyond domestic concerns, Pearson again had Canada’s international reputation in mind. Back in 1957, during the Suez Crisis, Egyptian President Nasser rejected the involvement of Canadian troops in the peacekeeping effort, on account of their neutrality being compromised by having the Union Jack on their British inspired uniforms.15

Thousands of entries for a new flag design were submitted to a fifteen-member, multi-party committee. The design approved by the committee was submitted by historian George F.G. Stanley, known most for his work on Louis Riel and the rebellions in Canada’s North-West.

Alternative Designs

Stanley described his winning design, and included a rough sketch of his idea in a memorandum to John Ross Matheson:

Stanley was clearly inspired by the Royal Military College of Canada flag:

Stanley and Matheson finalized the Maple Leaf design, and a more professional drawing was made by the graphic artist Jacques Saint-Cyr.

The simple red and white Maple Leaf flag was unanimously approved by the committee 14-0. The Conservatives on the committee voted against the ‘Pearson Pennant’, and the Liberals actually liked Stanley and Matheson’s design better as well. The new flag was approved by the House of Commons on December 15, 1964, by a vote of 163 to 78.

This new symbol of unity was deliberately designed to exclude and minimize the traditional symbols tied to Canada’s European founding peoples.

Diefenbaker’s Lament

There was pushback and debate throughout this entire period in which Canada’s national identity and symbols were changed. There was only a brief respite of federal Liberal control of this process. It came with the Progressive Conservative government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, from 1957-63.

For many, “Dief the Chief” embodied a last gasp of pre-1960s Canadian nationalism. English Canadians who were loyal to British institutions and traditions looked to Diefenbaker to ward off transformation of the country. Philosopher George Grant’s 1965 book Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism, features Diefenbaker as the embattled protagonist, who ultimately loses this fight.

For all of the troubles in Quebec in the 1960s and 70s, George Grant viewed the changes and uncertainty in English Canada as even more destructive in the long-term to fostering a new national identity. Grant said in 1973:

Canada originally was put together by two groups of people who didn’t have much in common but didn’t want to be Americans… I think the French have gone on knowing why they are not Americans. I think it’s very hard for English speaking Canadians.16

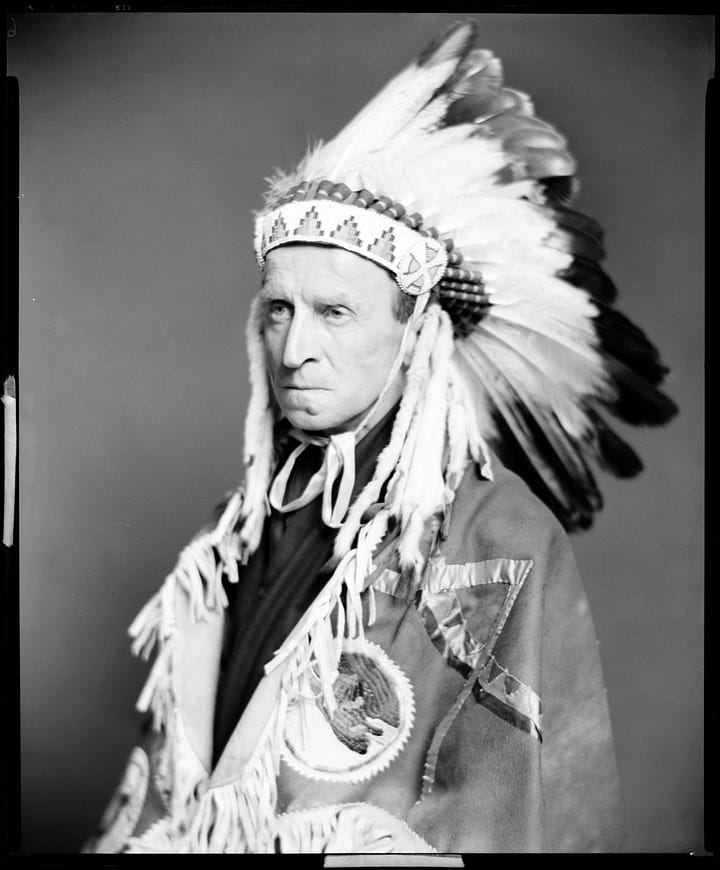

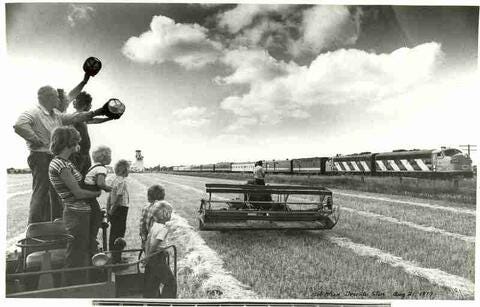

As Prime Minister and later Leader of the Opposition, Diefenbaker offered a passionate defense of Canada’s traditional character. Boisterous, unapologetically patriotic, emotional, and a friend of the everyman, Diefenbaker wore his heart on his sleeve. His jowls and pointed gesticulations lent well to caricature.

In Diefenbaker’s sentimental and dramatic speeches was a genuine concern and affection for the lowly, and a love for his country and its people.

Diefenbaker strongly favoured retaining the Red Ensign, and he wanted a referendum to decide the issue. Canadians were far from united—a Gallup poll from August 1964 found that 48 per cent supported the Pearson pennant, with 41 per cent opposed.17

But Diefenbaker also represented some of the beginnings of the ‘new nationalism’ in the 1960s. He was the first Prime Minister who was not of English or French descent; his mother of Scottish heritage and his father a recent German immigrant.

Diefenbaker’s parents moved from Ontario to the North-West in the early 1900s; settling in the newly created province of Saskatchewan. Diefenbaker grew up in the quickly growing city of Saskatoon. He would use his upbringing as a prairie boy to show he would stand up for the common man, outside of the centres of economic and political power in the east.

John Diefenbaker: “Some said, I was too much concerned with the average Canadian. My answer was, I can’t help that. I’m one of them.”

For often being labelled an arch-conservative, Diefenbaker was at the forefront of progressive change of the age. The 1960 Canadian Bill of Rights was a personal project of Diefenbaker. It was a federal statute that did not apply to provincial laws, but it should be viewed as an important precursor to Pierre Trudeau’s 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Both focused on preventing discrimination, ensuring minority rights, and protecting civil liberties.

Diefenbaker could be described as a civic nationalist. He believed ethnicity played a secondary role to shared values and principles, and that truly anyone could ‘become Canadian’. Duty and loyalty were more important to Diefenbaker than blood. Hence his insistence on opposing “hyphenated Canadians” in 1958:

I am the first prime minister of this country of neither altogether English or French origin. So I determined to bring about a Canadian citizenship that knew no hyphenated consideration… I’m very happy to be able to say that in the House of Commons today in my party we have members of Italian, Dutch, German, Scandinavian, Chinese and Ukrainian origin — and they are all Canadians.18

In 1962, Diefenbaker also altered Canada’s immigration policy. Prime Minister Pearson would later expand upon Diefenbaker’s changes:

The [1962] immigration regulations specified that non-sponsored immigrants would be assessed on the basis of their education, training, skills or other special qualifications rather than their race, ethnicity or national origin… the classes of sponsored immigrants were also expanded.19

Diefenbaker’s conception of Canada’s multicultural character was stated in terms more digestible to conservatives—that there was inherent value in doing things in opposition to the United States:

[Canada is not] a melting pot in which the individuality of each element is destroyed in order to produce a new and totally different element. It is rather a garden into which have been transplanted the hardiest and brightest flowers from many lands, each retaining in its new environment the best of the qualities for which it was loved and prized in its native land.”20

This was part of a speech given in 1961, in Winnipeg, at an event commemorating the 70th anniversary of Ukrainian settlement in Canada.

60 years removed from the Great Flag Debates, it is difficult for us to put ourselves in Diefenbaker’s shoes. What exactly was he fighting against? What was there left to conserve when the Empire itself was changing along the same lines as Canada?

George Grant could see, and Diefenbaker likely felt, that someone had to come to English Canada’s defense in her hour of need. Even as he instituted similar changes as his political opponents—Diefenbaker called for caution in cementing the transformation of the country’s identity and symbols.

Diefenbaker was both a defender of the centre—the Empire and its traditions—as well as increasingly marginal groups—the ‘average Canadians’ and their concerns. Diefenbaker’s transitional, in-between position in Canada was visible at his funeral. We can see an acceptance of his place in history through his casket—draped in both the Red Ensign and the Maple Leaf flags.

Multiculturalism and Negation of Identity

We’ve been interpreting changes in Canada through two different concepts—formation and transformation, as characterized by writer Matthieu Pageau:

formation is a process by which an identity produces “more of itself and less of the other” by integrating matter. Like the growth of a tree, this process begins with a singular identity (seed) that expands into a coherent structure. This is not change in the ancient sense of transformation, a process that creates “less of itself and more of the other”. Simply stated, change means turning something into something else, whereas formation means producing a greater version of something.21 [italics added]

In some respects, the 1960s and 70s were still a period of formation in Canada. We simply followed the lead of Britain as we always had. Canada became “more of ourselves” by emulating liberal British ideas, even as our leadership tried their best to reject our Britishness.

But this was also a transitional period. As Britain decolonized, and the centre of the Empire receded, the centre in Canada followed. The changes to Canada’s national symbols, immigration policy, and attitudes towards our own culture and religion transformed Canada, making it “less of itself and more of the other”.

These changes which transformed Canada were based on a willful negation or ‘self-emptying’ of identity. These ideas continue to carry much cultural weight because of their Christian origins and connotations.

Negation of identity and self-emptying are present in the person of Christ Himself. Kenosis is the Greek word used in the Gospels, to refer to the willful lowering of Christ to take on a human form—becoming both fully God and fully man. In doing so, Christ makes Himself perfectly obedient and receptive to the will of the Father. He sacrifices Himself towards the highest good.

It was through this obedience to the divine will that Christ was able to make the ultimate sacrifice of Himself, which redeemed humanity.

St. Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians calls on us to emulate Christ’s self-emptying and obedience in our own lives:

5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, 7 but emptied himself, [kenóō] taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. 8 And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross. 9 Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, 10 that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Philippians 2:5-11)

It is this process which multiculturalism attempts to mimic. Proponents of multiculturalism are correct that it is only in deliberately giving up and negating a piece of ourselves that we earn a newer and greater identity.

But, Christians sacrifice what we were in order to gain a unity in God that we cannot find on our own. In the words of St. Maximos the Confessor:

Just as ignorance divides those who are deluded, so the presence of spiritual light draws together and unites those whom it enlightens. It makes them perfect and brings them back to what really exists; converting them from a multiplicity of opinions it unites their varied points of view - or, more accurately, their fantasies - into one simple, true and pure spiritual knowledge, and fills them with a single unifying light.22

Multiculturalism promises a similar unity from diversity, and through the sacrifice of the centre to the margins. But multiculturalism pursues negation for its own sake, and holds this up as the highest good. Whereas in moving toward Christ, we ultimately become more of ourselves—not less.

The battles to go beyond negation in Canada, and to foster a positive national identity, were fought and lost long ago. Both the ‘last gasp’ of pre-1960s Canadian nationalism characterized by George Grant and John Diefenbaker, and the ‘new nationalism’ of Lester Pearson, relied on negation.

This can be seen in our symbols. The visual language available in Canada today to express any sort of national sentiment, or rebel against the established order, are products of a consensus built upon negation of identity.

In the 1960s and 70s, Canadians were caught between worlds. We faced the options of ‘no longer being British’ or ‘not becoming American’—without a positive affirmation to choose from. If Britain no longer believed in the Empire, how could we? And if English Canadians no longer identified with Britain, why not ‘become American’? What then would stop Quebec from going on its own?

Officially adopting multiculturalism appeared to be a solution to these problems.

Next in this series: We will turn to the most important figure in advancing these ideas into legislation and the public consciousness. The man who led the fight to keep Quebec in Canada, and founded the nation anew with multiculturalism as our new national identity: Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

Pageau, Matthieu. The Language of Creation: Cosmic Symbolism in Genesis: A Commentary. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, May 2018), 135-36.

Henshaw. Peter. “John Buchan and the British imperial origins of Canadian multiculturalism”, in N. Hilmer and A. Chapnick, eds, Canadas of the Mind: The Making and Unmaking of Canadian Nationalisms in the Twentieth Century (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s, 2007).

The term ‘mosaic’ to describe Canada was also used previously by Kate Foster in 1926, in her book Our Canadian Mosaic.

Gibbon, J. Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1938), 307.

Peter Henshaw, “John Buchan and the British imperial origins of Canadian multiculturalism”, 202.

Creighton, Donald. Canada's First Century. (MacMillan, Jan. 1 1970), 277.

Triadafilopoulos, Triadafilos. Becoming Multicultural: Immigration and the Politics of Membership in Canada and Germany. (UBC Press, 2012), 58.

Blanding, Lee. Re-branding Canada: The Origins of Canadian Multiculturalism Policy, 1945-1974. (University of Victoria, 2013), 26.

Blanding, 27.

Triadafilopoulos, 103.

Discussed previously in Multicultural Symbolism II.

Champion, C.P. The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism, 1964-68. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010), 231.

The Front de libération du Québec. The FLQ were the most prominent of militant groups which formed during this time with the goal of separating Quebec from English Canada. They will be discussed further in the next post.

Matheson, John Ross. Canada’s Flag: A Search for a Country. (Mika Pub Co 1986), xiv.

Grant, George. “George Grant, Canadian Philosopher,” at 0:32. CBC.ca, 1973.

Diefenbaker, John. “John G. Diefenbaker – Canada’s 13th Prime Minister,” Library and Archives Canada. Government of Canada. March 29, 1958. Quoted in, ed. Raymond Blake. Canada and Speeches from the Throne: Narrating a Nation, 1935-2015. (University of Regina, 2020), 18.

Diefenbaker, John. “Notes of Speech by the Prime Minister, the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker, Q.C., M.P., on the Anniversary of the Ukrainian Canadian Settlement in Canada and in Commemoration to Taras Shevchenko, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 9 July 1961”.

Matthieu Pageau, The Language of Creation. 135-36.

St Maximos the Confessor. ‘Various Texts on Theology, the Divine Economy, and Virtue and Vice’, in the Philokalia, 514.