Christians believe that God has written the law onto the heart of every man.1 But, because of free will and man’s corruption through his own sin, these laws which were intended to be implicit often need to be made explicit in our societies.

The archetypal story of ‘handing down laws’ is the Ten Commandments. Moses served as an intermediary between the knowledge of God and his laws, and the Israelites. It was Moses alone who was capable of ascending the mountain to receive and then bring these rules to the people.

In a modern democracy, we repeatedly act out ancient stories like the Ten Commandments even if we do not realize it. The ritual of voting calls on members of our community to act like Moses: as they are raised up to a position of authority, with the hope that they embody and enforce the principles or ‘rules’ of our society.

In this series we’ve covered the process of Canada becoming multicultural. If there is one figure who ‘handed down the laws’ of multiculturalism to the Canadian people, it is Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

Pierre Trudeau cemented major changes to the ‘rules’ which govern Canada. As Prime Minister from 1968-79, and again from 1980-84, Trudeau is arguably the most important figure in instantiating multiculturalism into the public consciousness.

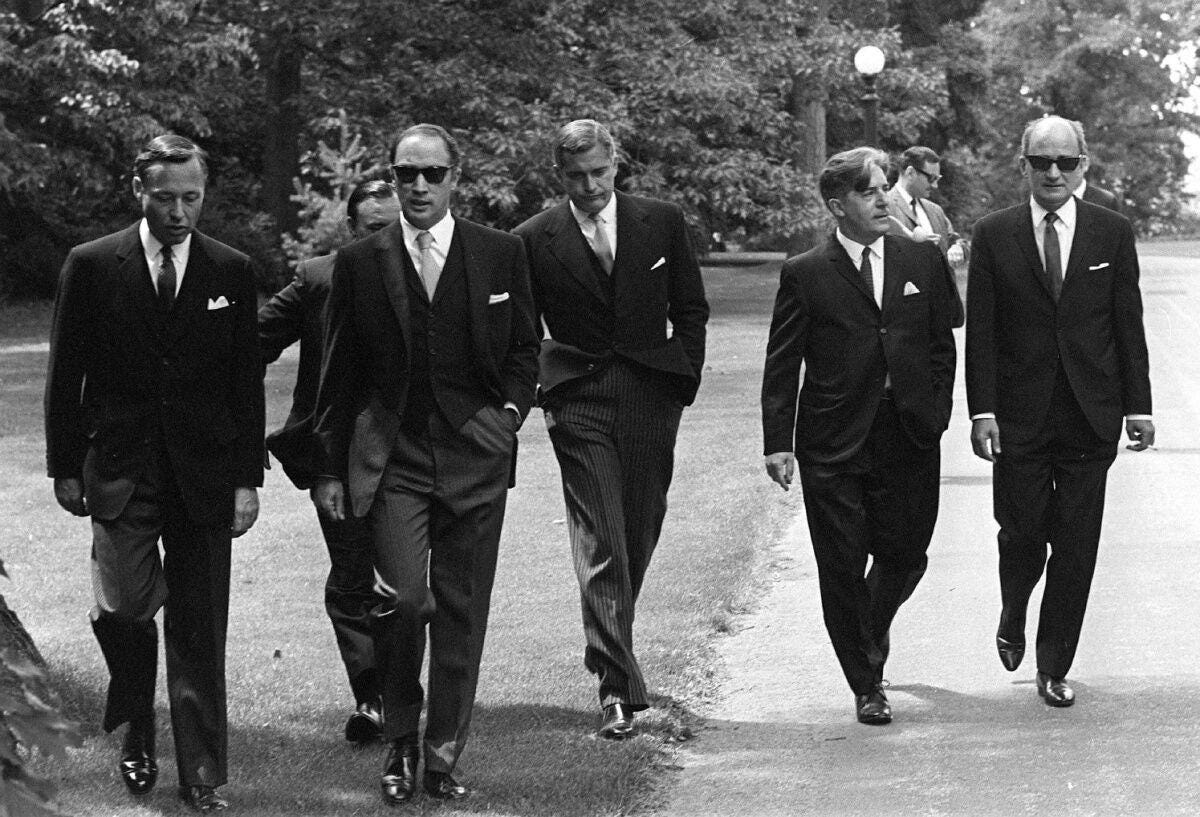

Trudeau was from a small, entrenched group of Canadians who formed the traditional centre—those with deep connections to the founding stock of the nation, who controlled important institutions and positions of authority, and helped to facilitate this shift of Canadian identity and character.

Trudeau imprinted his vision onto Canada in a way that rivals the nation’s founder, Sir John A. Macdonald. In many ways, Canadians owe the current state of the country to Pierre Trudeau.

The Young Pierre Elliot

Pierre Elliot Trudeau grew up in Outrement, a suburb of Montreal, between English and French social and cultural life. The descendant of French-Canadian habitant farmers on one side of his family, and British Loyalists who left the United States on the other2, Trudeau was uniquely suited to navigate the worlds of English and French Canada.

Trudeau excelled at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, becoming fully immersed in a traditional French-Catholic Jesuit education from a young age. Usually at the top of his class, Trudeau developed a lifelong discipline and passion for intellectual pursuits.

Born in 1919, Trudeau thrived as a student amidst a revival of Catholic intellectual activity which spread to Quebec from France, around the time of the First World War. He was devoted equally to his schoolwork as his faith, dutifully attending lectures and mass. Trudeau also came to identify with a French national identity through his education.

But, there were some ways that Trudeau did not fit into traditional Quebec. Pierre’s father Charles had left the legal profession and made a fortune in the booming automobile industry in the 1920s and 30s, buying and building gas stations around Montreal. The young Pierre was not enough of a Quebec nationalist to dismiss the advantages of an upper-class North American lifestyle. This included gallivanting to New York to catch a Broadway play, or spending summers on the beach in Maine at one of the family’s homes.

Still, the young Trudeau’s passion for his nation developed. In 1941, Trudeau believed that French-Canadians had little obligation to fight a war in Europe between competing imperial powers. Instead, Trudeau’s patriotism preferred to emulate the spirit of romantic adventurers.

Along with three of his friends, Trudeau followed the canoe route of Pierre-Espirit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, from the Ottawa River up to Hudson Bay.3 These were the two great French explorers and coureur des bois who contributed to the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The presence of servants in the family home did not stop the young Pierre from expounding on the excesses of the rich. He saw no problem playing rebel on his Harley-Davidson, then coming home to his doting mother, patiently waiting for his return so they could listen to classical music together.4

In these behaviours and beliefs which could be called hypocritical is an important insight into what may be Trudeau’s central guiding principle. And that is a personal determination to shape identity, rather than let it be imposed upon him: first his own identity as a young man, then the nation’s identity, as Prime Minister.

The Young Pierre Elliot’s life was a microcosm of the nation as he knew it—English and French inseparably bound together, yet in discordance, with total separation being an impossibility; akin to death or undoing all together.

Trudeau the Intellectual

Trudeau followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a lawyer upon graduating from the University of Montreal. But much like his father, he found the profession wanting. Pierre quickly found himself back in school.

After the Second World War, Trudeau embarked on an an intellectual and cultural odyssey across postwar Europe.5 He began his journey out of the conservative Quebec of his youth into a global hub of intellectuals and their ideas. We can see a noticeable shift in his thinking in these years. Trudeau’s first stop was Harvard, where he earned a graduate degree in economics.

In 1946, Trudeau travelled to Paris, where he met with and attended lectures by prominent French Catholic intellectuals like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Étienne Gilson and Emmanuel Mounier.

Trudeau was finding some solutions in his travels between identities and belief systems. He moved on from Paris to the London School of Economics, where he became friendly with socialist economist Harold Laski, and attended lectures by historian Arnold Toynbee and philosopher Bertrand Russell.

Leaving Europe, Trudeau then backpacked across the Middle East and Asia, armed with a British passport and the guise of conducting research for a Harvard dissertation on communism and Christianity.6

Trudeau returned to Quebec in 1948. He briefly worked in the federal civil service in the early 1950s, but quickly grew bored of Ottawa, and headed back to Quebec to continue developing his ideas.

Trudeau was among the founding members of Cité libre, which became an an influential political journal in 1950s Quebec. The journal discussed topics which drove the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s—including the role and function of the Church in everyday life; the question of Quebec’s future as a separate state; and the importance of civil liberties and minority rights. Many have emphasized Cité libre as a voice of opposition to Quebec's longest serving premier, Maurice Duplessis, who embodied 1950s Quebec conservatism.

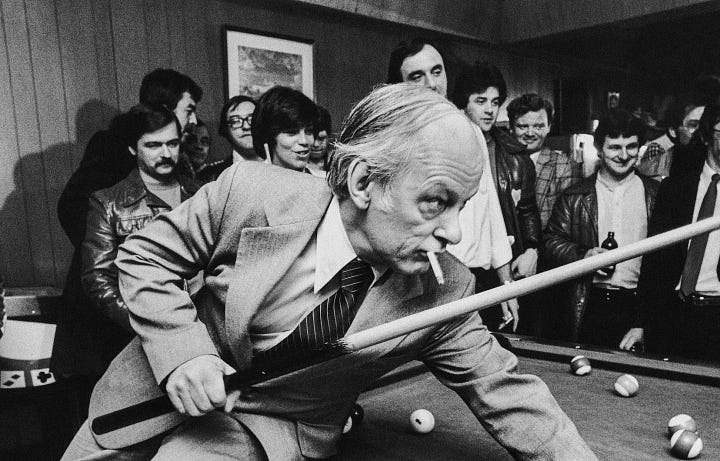

Throughout the 1950s into the 60s, Trudeau continued to travel. Now his trips resembled a world tour of communist hotspots. In 1952, Trudeau entered Stalin’s Soviet Union in its last days, under reporter’s credentials. In 1960, he made his way with several other French-Canadians to Mao Zedong’s China, on a state-sponsored tour.

Trudeau arrived in China in the middle of Mao’s attempt to industrialize the nation, known as the Great Leap Forward. Tens of millions died of starvation amidst famine caused by forced agricultural collectivization.

Trudeau co-wrote a book about the trip with his close friend, Quebec politician Jacques Hébert—entitled Two Innocents in Red China. The book reads as if one took seriously the claims made on an ‘official tour’ of North Korea today:

In all our travels, even the unplanned ones, and in the poorest quarters, we had never met a beggar or seen the stinking filth that is characteristic of nearly every road in Asia… We knew that those dormitory buildings rising up on the approaches to Peking were duplicated in incalculable numbers in all the suburbs of all the industrial cities of China… We know that they are no longer travelling on the ‘classic road of Asia’. They are travelling the road of the future, a future so filled with promise and with trials that even the most audacious planners cannot trace its outline.7

Repeatedly, it seemed that the downsides of communism were a blind spot for Trudeau and his circle. In 1983, a year before stepping down as Liberal leader, Trudeau would appoint his co-author Hébert to the Senate.

In the same year upon returning from China, Trudeau and a few friends attempted to visit Cuba, by rowing from Key West, Florida. The trip was abandoned due to inclement weather. But Trudeau would not be discouraged—as Prime Minister he would forge a long-lasting personal relationship with Fidel Castro.

Back in 1960s Quebec, the political situation seemed ripe for change. The defeat of fascism, mounting evidence of the crimes of the Soviet Union, and the shortcomings of American-rule of the postwar order, left many of Trudeau’s generation to consider tearing down all that had come before politically and starting fresh.

In the first issue of Cité libre Trudeau explained a ‘functional’ approach to politics, in which all things were subject to change and scrutiny:

We want to bear witness to the Christian and French fact in America. Fine; so be it. But let’s get rid of all the rest. We should subject to methodical doubt all the political categories relegated to us by the previous generation; the strategy of resistance is no longer conductive to the fulfillment of our society. The time has come to borrow the “functional” discipline from architecture, to throw to the winds those many prejudices with which the past has encumbered the present, and to build for the new man. Let’s batter down the totems, let’s break the taboos. Better yet, let’s consider them null and void. Let us be coolly intelligent.8

Trudeau continued to raise his profile in Quebec politics, lending his legal expertise to the labour movement. By 1956, Trudeau became a recognized authority on the Canadian constitution and division of powers through his work on the Tremblay Commission, which focused on the problem of federal and provincial tax sharing.9 He also worked as an associate professor of law at the University of Montreal, from 1961 to 1965.

By 1965, after forming an impressive intellectual, political, and cultural resume, through years of writing, teaching, and travelling, Trudeau finally decided to enter federal politics.

Trudeaumania

In the 1960s, increasing numbers of French-Canadians wanted their political and national identity to be embodied in a state separate from Canada. This was an impossibility for Trudeau.

Trudeau’s vision of Canada was similar to himself—without its mix of English and French identities it would cease to exist. Trudeau became one of the foremost opponents of Quebec separatism. His enemies in the movement would often refer to him as ‘Elliot’—emphasizing his English heritage from his mother’s side.

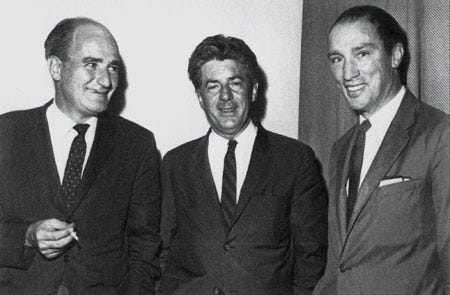

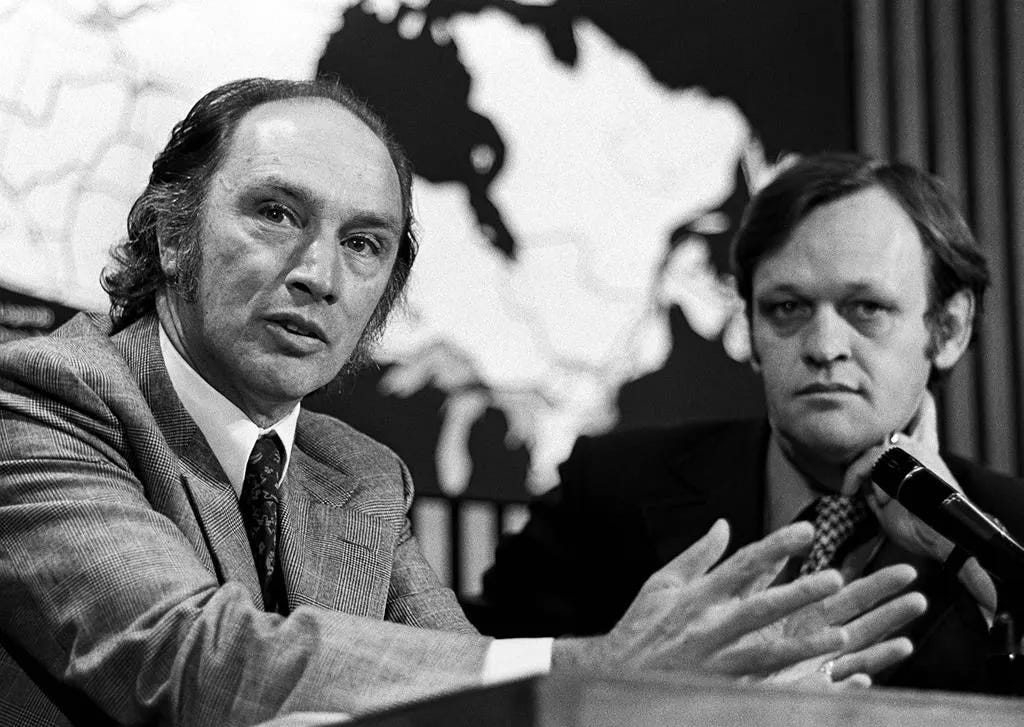

A major reason for Trudeau making the jump to federal politics was to combat Quebec separatism. Trudeau was accompanied by his close friends Gérard Pelletier and Jean Marchand to Ottawa. They were dubbed the “The Three Wise Men” by the media. Intelligent, shrewd, witty, and French, they were a new breed on the national stage. All three ran as Liberals and were successfully elected in 1965.

Throughout the 1960s, the three men had ongoing debates about the future of Quebec and Canada, usually at Pelletier’s home. A small circle was formed at these regular meetings, who went on to occupy positions of power and influence.

Also present were André Laurendeau, journalist and future co-chair of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, and future Quebec Premier René Lévesque. Lévesque was an early supporter of Quebec separatism, and in the early 1960s he was well-known in Quebec as a reporter and for his political talk show Point de mire.

From debates around Pelletier’s kitchen table, now in Parliament, Trudeau was able to quickly establish himself in the national spotlight. He was quickly promoted to serve in Prime Minister Pearson’s cabinet as Minister of Justice and Attorney General. In this role, Trudeau began to put his theories into law.

Trudeau was the face of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1968–69, which included decriminalization of private homosexual acts, the altering of abortion and divorce laws, and addressing of other contentious issues such as gambling and gun control. Trudeau explained the bill to the press:

In terms of the subject matter it deals with, I feel that it has knocked down a lot of totems and overwritten a lot of taboos, and I feel in that sense it is new, but it’s bringing the laws of the land up to contemporary society I think. Take this thing on homosexuality, I think the view we take here is that there is no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation, and I think that you know, what’s done in private between adults doesn’t concern the criminal code. When it becomes public it’s a different matter.10

Trudeau framed these changes as simply embodying the dominant or democratic will of the people—the laws were not being ‘handed down from above’, but ‘brought up to contemporary society’.

By the late 1960s, there had been decades of Liberal Prime Ministers who were effective, popular, and principled—but less than exciting. All the way from Mackenzie King, through St. Laurent, and then Pearson. Trudeau had eyes on bucking this trend.

He had arrived at precisely the right time, just as the nation was celebrating its centennial in 1967. There was an effort to assess where the country had been, where it was going, and what kind of leader would be needed for the future. The spirit of the age was exemplified by the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, commonly called Expo 67, held in Montreal.

Spring 1968 was filled with change in politics and culture around the Western world. In Canada, Pearson had stepped down, and Trudeau was on the campaign trail as a new election was called.

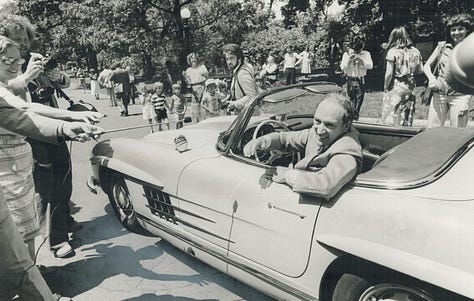

Trudeau’s Liberal predecessors may have paved the way for him in policy, but in personality and attitude he was night and day. It felt like Canada was finally with the times. The next potential Prime Minister was a cultured, suave intellectual; easy to juxtapose against most politicians.

Trudeau’s quick rise to stardom was referred to as “Trudeaumania” by the media.

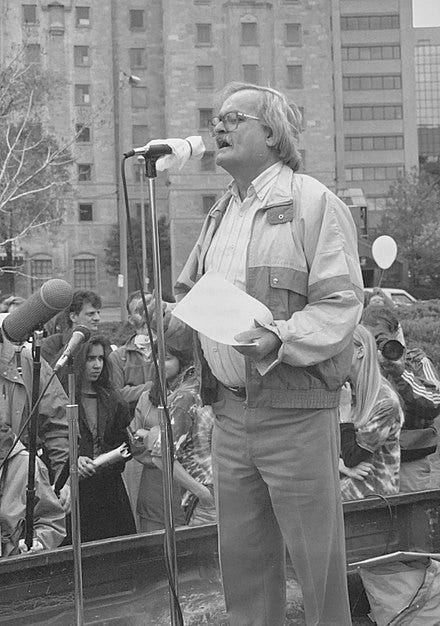

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1968–69, was a topic of discussion during the 1968 federal debate. Below is a clip of the debate featuring Tommy Douglas, leader of the New Democratic Party. Douglas was famous and beloved by many for introducing the first single-payer, universal health care program in North America as Premier of Saskatchewan.

A former Baptist minister, Douglas agreed with Trudeau on the importance of drawing a distinction between sin and crime. Here Douglas elaborates on the importance of Canadian society having a different approach to abortion and homosexuality (ends at 1:52:24):

Douglas shows, in a way that may be jarring for some today, just how conservative even progressive politics were in Canada. In 2004, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation aired a television series called ‘The Greatest Canadian’. Voters from around the country chose Tommy Douglas as number one. Pierre Trudeau came in third.11

In the 1968 election, the Liberals won a majority of 154 seats, as the Progressive Conservatives lost ground with 72, while the New Democrats scored 22. Trudeau had been given a clear mandate by the Canadian people. It would not take long for the simmering tensions in Quebec to boil over and provide Trudeau with a defining moment of his career.

Just Watch Me

While Trudeau was taking power in Ottawa, his old debate combatant René Lévesque formed a political party of his own, back home in Quebec. In 1968, Lévesque had left the Quebec Liberals with his supporters, and joined forces with Gilles Grégoire of the Quebec separatist party Ralliement National, to form the new Parti Québécois.

The increasing usage of the word ‘Québécois’ reflected the secular and nationalist direction of French-Canadian society, as many broke away from their past and were now attempting to rewrite the ‘laws’ of their nation as they saw it. Lévesque’s Parti Québécois promised to propose a vote to separate Quebec from Canada if elected.

The radical wing of the separatist movement wished to leave Canada through violent means. The most prominent militant separatist group was the The Front de libération du Québec or ‘the FLQ’.

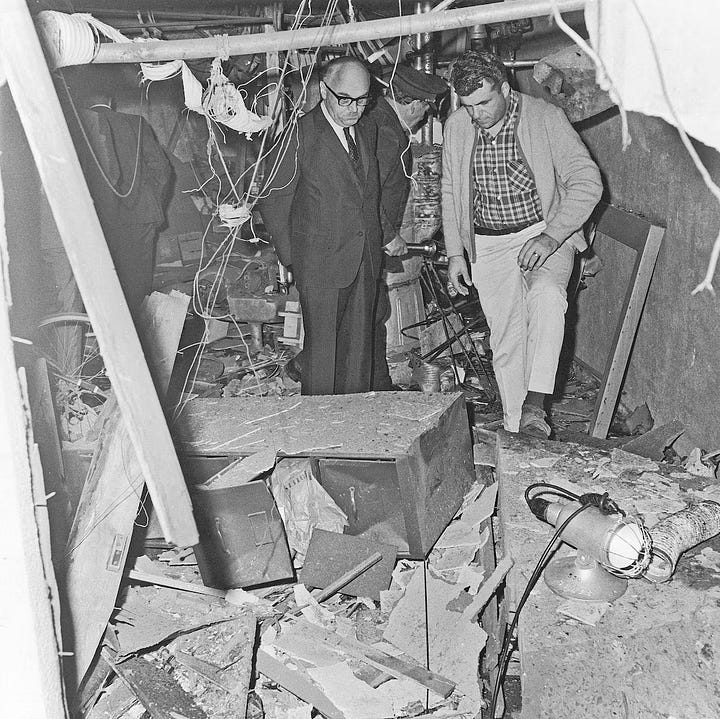

The FLQ committed sporadic terrorist attacks throughout the 1960s in Quebec—totaling some 170 violent attacks, which killed eight people and injured many more; mostly through bombings.12 Bombings were carried out at Montreal City Hall, the mayor’s home, and several other locations. The bombings culminated in an explosion which hit the Montreal Stock Exchange on February 13, 1969, in which twenty-seven people were injured.

By 1970, the bombings gave way to brazen kidnappings of public officials.

The October Crisis, as it came to be known, occurred in October 1970 when members of the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross. Then five days later, FLQ members kidnapped Pierre Laporte, Deputy Premier of Quebec.

Trudeau was shocked and outraged by the kidnapping of Cross, but Laporte he knew personally. Trudeau and Laporte went to school together at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, as their fathers had before them.

The FLQ had a list of demands to release the two hostages, which included the dissemination of the FLQ’s manifesto. The manifesto was broadcasted by CBC/Radio-Canada across the province in French and English on October 8, 1970.

Laden with their usual Marxist and anti-colonial rhetoric, the FLQ manifesto ridiculed Jean Drapeau, mayor of Montreal; Robert Bourassa, Premier of Quebec; and Prime Minister Trudeau, as merely weak puppets of the true rulers of Quebec—wealthy Anglo interests:

We live in a society of terrorized slaves, terrorized by the big bosses like Steinberg, Clark, Bronfman, Smith, Neaple, Timmins, Geoffrion, J.L. Lévesque, Hershorn, Thompson, Nesbitt, Desmarais, Kierans. Compared to them, Rémi Popol the nightstick, Drapeau the “dog,” Bourassa the twink of the Simards, and Trudeau the f*ggot are peanut politicians!13

The FLQ shared much in common with today’s proponents of change. But they were limited in their acceptance of all marginal groups.

On October 13, at the height of the crisis, CBC reporter Tim Ralfe and Peter Reilly of CJON-TV questioned Trudeau as he was exiting his car on Parliament Hill. At this point, the army was being used to guard certain high-profile public officials in Quebec and Ottawa. And the FLQ was demanding the release of jailed FLQ members who they claimed were ‘political prisoners’.

In the interview, Trudeau plainly expressed his political philosophy, and displayed a coolness and will to maintain order. He emphasized the importance of not allowing groups like the FLQ to threaten the functioning of Canadian society—in other words to try and ‘hand down the law’ from the bottom-up.

When asked how far he would go to maintain order, he famously responded “just watch me” (at 5:43, but the whole clip is worth watching):

Three days later, on October 16, Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, which had never been used in peacetime. The act suspended civil liberties—giving extra powers to police to arrest and detain those under suspicion of being connected to the kidnappings.

Invoking the act was met with surprised approval by many who did not support Trudeau or the Liberals, while some of his allies were worried about his newfound authoritarian streak. The Canadian public, English and French, overwhelmingly approved of invoking the War Measures Act in opinion polling.14

On the night of October 17, the FLQ announced that Pierre Laporte had been murdered. Police were led to a car parked at Montreal’s St. Hubert airport; and in the trunk laid Laporte’s body.

On December 3, the remaining hostage, James Cross, was eventually released following negotiations between the FLQ and police. On December 28 Laporte’s murderers were apprehended at a farmhouse outside of Montreal. By January, Trudeau ordered the troops to withdraw, and The October Crisis was at an end.

Trudeau did not hesitate in using the powers at his disposal to maintain order, and was widely approved in doing so, even by people who despised him. He would not allow for the margins to enact change through violent means. If the country was to be transformed, it would come from the top-down.

Multiculturalism as Policy

It was during The October Crisis that Trudeau was trying to transform the country and ‘hand down the laws’ of multiculturalism. The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism concluded in 1969. Trudeau implemented some of its recommendations, but he also had ideas to expand their findings in order to cut through the tensions between English and French Canada.

The Official Languages Act of 1969 made Canada officially bilingual. It required all federal institutions to provide services in English or French. It was hoped that these provisions would accommodate the concerns of French-Canadians, and increase their representation in the public service.

This fulfilled the bilingual aspect of the commission. But like Paul Yuzyk and Jaroslav Rudnyckyj, two of the most prominent Ukrainian-Canadian proponents of multiculturalism, Trudeau was not in favour of the bicultural aspect of the commission.

Here was the problem from Trudeau’s point of view: If Canada’s cultural identity was officially declared English and French, and these two societies were declared equal and united now, they could be equal and separate later.

As early as 1962, Trudeau wrote that pluralism was the only way forward for Canada. Trudeau foresaw a future where nation-states who refused to acknowledge this would become subject to an ever-increasing encroachment of the margins:

The very idea of the nation-state is absurd. To insist that a particular nationality must have complete sovereign power is to pursue a self-destructive end. Because every national minority will find, at the very moment of its liberation, a new minority within its bosom which in turn must be allowed the right to demand its freedom. And on and on would stretch the train of revolutions, until the last-born of nation-states turned to violence to put an end to the very principle that gave it birth. That is why the principle of nationality has brought to the world two centuries of war, and not one single final solution.15

The leader of a nation-state had only contempt for the principle of nationality.

Trudeau did not hide his plans for transforming Canada, where “the rights of minorities will be safe from the whims of intolerant majorities”.16 We would be different than the United States and their melting pot—we instead would be a mosaic of cultures and identities.

Trudeau stated that favouring the marginal would require sacrifice from the centre:

English Canadians, with their own nationalism, will have to retire gracefully to their proper place, consenting to modify their own precious image of what Canada ought to be. If they care to protect and realize their own special ethnic qualities, they should do it within [a] framework of regional and local autonomy rather than a pan-Canadian one.17

On October 8, 1971, Trudeau introduced a federal policy of ‘multiculturalism within a bilingual framework.’ Supported by federal funding, the goals were:

To assist cultural groups to retain and foster their identity; to assist cultural groups to overcome barriers to their full participation in Canadian society; to promote creative exchanges among all Canadian cultural groups; and to assist immigrants in acquiring at least one of the two official languages.18

The next day, Trudeau spoke at a function, explaining the value of multiculturalism and diversity in Canada:

Uniformity is neither desirable nor possible in a country the size of Canada. We should not even be able to agree upon the kind of Canadian to choose as a model, let alone persuade most people to emulate it. There are few policies potentially more disastrous for Canada than to tell all Canadians that they must be alike. There is no such thing as a model or ideal Canadian. What could be more absurd than the concept of an “all-Canadian” boy or girl? A society which emphasizes uniformity is one which creates intolerance and hate. A society which eulogizes the average citizen is one which breeds mediocrity. What the world should be seeking, and what in Canada we must continue to cherish, are not concepts of uniformity but human values: compassion, love, and understanding.19

Trudeau delivered these marks in Winnipeg, at the tenth congress of the Ukrainian Canadian Committee.

Lévesque’s Response

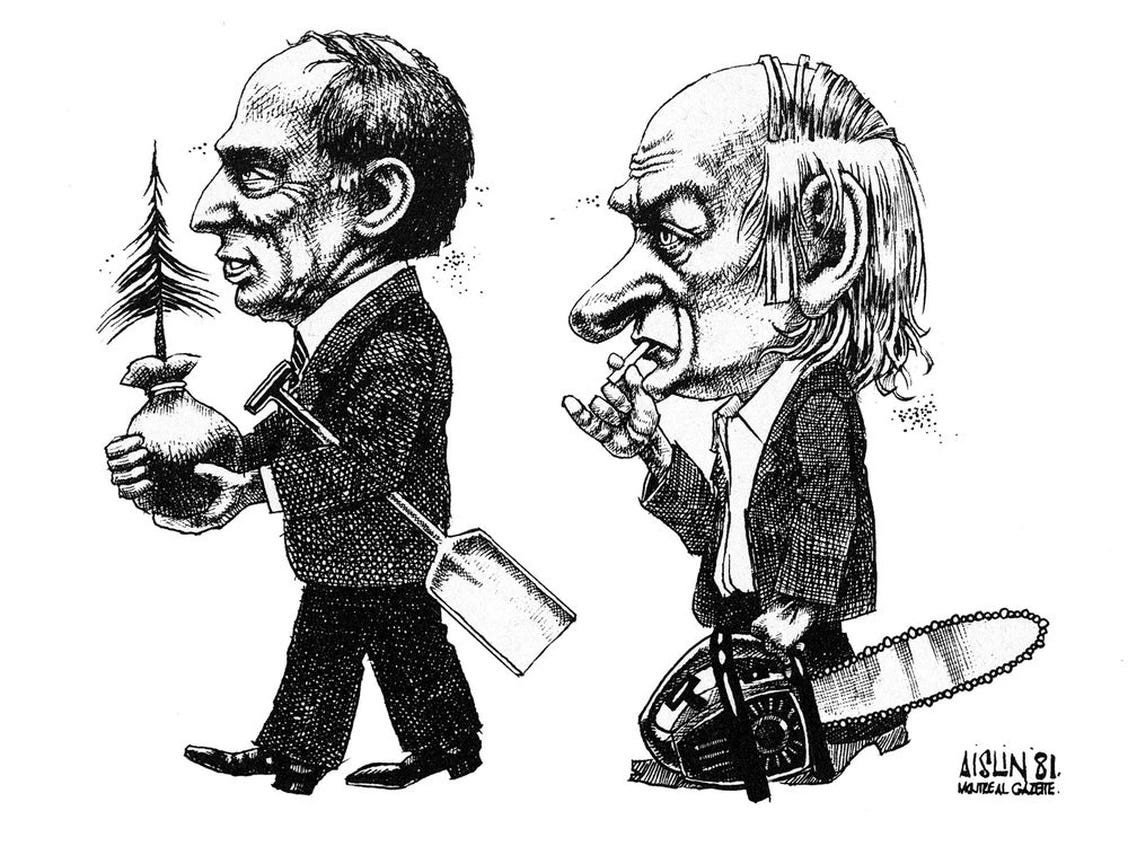

Multiculturalism as a federal policy did not require Quebec’s approval. And it did not prove to be a solution to the problems between the two Canadas. Five years after Trudeau’s multiculturalism policy went into effect, René Lévesque was elected Premier of Quebec, coming into office with a landslide victory in the 1976 provincial election.

Trudeau and Lévesque would continue their fight to implement their visions for their nations. Each with their own sets of laws they hoped to hand down to their people.

A major piece of legislation introduced by Lévesque’s Quebec government was the Charter of the French Language, 1977 or ‘Bill 101’. The main objective of which was “to make French the language of Government and the Law, as well as the normal and everyday language of work, instruction, communication, commerce and business.”20

For new immigrants to Quebec, this meant that their children would learn French in school, and businesses were required to have all exterior signage in French. The act became a cornerstone of the new secularly oriented, nationally minded state of affairs in the province.

Lévesque’s language legislation encouraged immigrants to conform to secular Québécois culture. It became law just after the federal Immigration Act of 1976, which reflected Trudeau’s vision for transforming Canada’s character.

One writer explains how Trudeau’s 1976 act differed from the usual federal immigration practices of the past:

In less than thirty years, the country had seen a remarkable shift from Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s vision in 1947: race and concerns about preserving Canada’s demographic character were no longer major considerations for admission… An unprecedented political and public consensus had emerged during this period on the basic elements of a generally liberal immigration policy.21

Trudeau had always been determined not to allow something like blood or place of birth to ultimately define his identity. In his mind, if he could manage it, Canada could too.

Beyond language rights, the key election promise of Lévesque’s Parti Québécois was to hold a referendum on Quebec becoming a sovereign nation. Trudeau had entered federal politics largely because he feared that this would happen. Now it had come to pass, and if Trudeau was unable to keep Quebec and Canada united as one, it would be an undoing of not only his political and intellectual beliefs, but perhaps his own identity, and the way that he lived his own life.

The referendum took place on May 20, 1980. The proposal to separate was rejected by Quebec voters 59.56% to 40.44%.

This was a clear setback for separatists and a great victory for Trudeau. But Quebec separatism wasn’t going away anytime soon.

Trudeau’s Second Founding

In the early 1980s, in his last few years as Prime Minister, Trudeau acted as a separatist. Trudeau, who despised nationalism in all forms, would embrace and cultivate the new Canadian nationalism which had been forming since the 1960s, and officially separate Canada from Britain.

The central symbols of this nationalism would be continuing the policy of multiculturalism, the patriation of the constitution from Britain, and the establishing of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The patriation of the constitution from Britain who allow for Canada to change its constitution in the future without British approval. It is seen as the final step in a ‘fully independent’ Canada.

Trudeau approached this defining project of amending the constitution with a tight group of trusted consultants and advisors, attuned to the highest ideals of what he termed a ‘Just Society’.

Writer Matthieu Pageau discusses how the modern ritual of nominating someone for a position in government is related to acts of anointing and tithing in the Bible:

In the Bible, transmissions of power and authority at the communal level are usually symbolized by tithing and anointing, Tithing is a transmission of matter and power from below, in which portions of material resources are “offered up” to support the head, and anointing is a transmission of meaning and authority (or ‘light) from above… in today’s world, these interactions are seen only as the practical necessities of a state, while they were probably seen as representations of cosmic patterns in the ancient world.22

Trudeau certainly believed in anointing only those worthy of carrying out his highest principles and ideals.

Trudeau and his circle attempted to carry out their duties in a similar vein to Moses, who had to prepare himself to receive God’s laws: Trudeau’s men achieved a purity of mind and body, (through acquiring education and credentials) ascended the mountain, (by being elected, reaching positions of power) received the law, (through adherence to their shared ideology) and then handed the laws down to the people (through legislation, education, and journalism).

Historian and journalist Peter C. Newman identified Trudeau’s Quebec lieutenant Marc Lalonde as “the first of a new breed of brilliant French-Canadian technocrats to move into a position of high influence within the Ottawa hierarchy.”23

Trudeau biographer John English listed several men who were involved in Trudeau’s inner circle as he assumed power: Michael Pitfield, a seasoned Ottawa civil servant; historian Ramsay Cook, who became a speechwriter for Trudeau; the Breton brothers, Albert, an economist; and Raymond, a sociologist; intellectual Fernand Cadieux; physicist Jim Davey; lawyer and academic Carl Goldenberg; and others.24

One gets the impression that Trudeau and his ilk viewed themselves as separate from the electorate. They were confident in the way things should be done, and the changes that needed to be made. Once they had received a mandate from the voters, they quickly made use of their authority to institute their principles, bringing along a willing yet ignorant public.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms—a new federal bill of rights—was the fullest expression of Trudeau’s ideals of a ‘Just Society’.

During negotiations to create the Charter, a very Canadian compromise was made between the federal and provincial negotiators—to include a ‘notwithstanding clause’. This is an option within the Charter which allows for provinces or the federal government to politely opt out of these newly codified, seemingly essential values which define us.

The notwithstanding clause shows Trudeau’s understanding that Canada’s political reality is defined by agreements between identities, and compromise. Regional concerns and public order ultimately outweighed a set of immutable principles or rights.

The Constitution Act, 1982 came into effect on April 17, 1982, as Queen Elizabeth II proclaimed the act on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Quebec was the lone province who refused to sign onto the agreement.

Trudeau had achieved his second founding, rewriting the most fundamental laws of the land. To establish the Charter as a new symbol, which was not embedded in any sort of tradition, new traditions began. In 1982, Dominion Day was renamed to Canada Day.

Pierre Trudeau’s Legacy

In 1984, Trudeau retired from politics and resigned as leader of the Liberal Party. Trudeau’s values, and what he believed were the values of most Canadians, were now embodied and enforced through the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and an amended constitution.

In Quebec, violent separatist demonstrations faded. But radical attitudes were allowed to lay dormant. By 1982, some of the convicted terrorists, murderers, and kidnappers who took part in The October Crisis, such as Paul Rose and Francis Simard, had already been granted parole. An undercurrent of resistance to the newly imposed order would remain in Quebec throughout the 1980s, and eventually lead to a second and much closer vote to separate Quebec from Canada in 1995.

Pierre Trudeau died on September 28, 2000. Trudeau’s funeral service demonstrated his unique place as an in-between figure. Not only in Canada, but a world leader.

Trudeau’s honorary pallbearers included Fidel Castro, President Jimmy Carter, the Aga Khan, and Leonard Cohen. Many other dignitaries were present, but it was Pierre’s son Justin, then 28, who stole the show. Justin delivered a eulogy for his father and ended his goodbye to thunderous applause as he wept over his father’s casket, draped in the Maple Leaf flag.

Pierre Elliot Trudeau is the most polarizing Prime Minister in Canada’s history. He waltzed into power in the late 1960s as a bold, charismatic, bright, natural leader. Throughout the 1970s he made sworn enemies of the separatists of his home province, and he was widely reviled throughout Western Canada for his natural resource policies.

By the 1980s, Trudeau had to be recognized as a statesman, regardless of one’s personal feelings towards him. Even if you hated him you had to respect him. He unapologetically used the means and opportunities at his disposal to usher in his vision for Canada. For most Canadians, it is his vision which is now celebrated every July 1st.

Earlier in this series we showed how multiculturalism in Canada did not begin with Pierre Trudeau. Since the settling of the North-West, the centre and margins both played a role in this shift of Canadian identity.

As Canada became officially multicultural, those who attempted to hold onto their ‘traditional’ identities like Lévesque in Quebec, or Diefenbaker in English Canada, ultimately ended up defining themselves negatively, just as Trudeau did. For Diefenbaker, Canadians would not be American, for Lévesque, Quebecers would not be Canadian.

Both Diefenbaker and Lévesque tried to anchor themselves to markers of identity—like the Red Ensign flag, or the French language, in an attempt to ward off transformation of their cultures. But it was already too late. Diefenbaker defended a connection to an Empire that had dismantled itself. Lévesque’s nationalism called for pride in a culture which had just hollowed out its spiritual foundations.

Pierre Trudeau acted as an inverse John A. Macdonald amidst these competing conceptions of identity. Trudeau presided over a deconstruction rather than a creation of national identity—as English and French Canadians were called together to become nothing in particular.

Trudeau, in the search for compromise between worlds, took the order which once supported a unique Canadian identity and dismantled others, and directed it inwards. The margins would now be put in the place of the centre.

A Last Word on the Law

Due to the fallen nature of man, we always have the potential to go astray. There’s no replacing the need for leaders to emerge, ‘ascend the mountain’ and ‘hand down laws’, to the people.

The Christian answer to the problem of hierarchy, proper leadership, and how we can aim at the correct things as a people, is the Church; the vessel between heaven and earth. Saint Gregory of Nyssa explains:

The multitude was not capable of hearing the voice from above but relied on Moses to learn by himself the secrets and to teach the people whatever doctrine he might learn from instruction from above. This is also true of the arrangement of the Church: Not all thrust themselves toward the apprehension of the mysteries, but, choosing from among themselves someone who is able to hear things divine, they give ear gratefully to him, considering trustworthy whatever they might hear from someone initiated into the divine mysteries.25

Participation in this system doesn’t require knowledge of high-minded political or philosophical theories—even the laws of Moses have been superseded. Instead, Christian law comes directly from the Word, who hands down not abstract concepts—but Himself.

Ultimately, there is no political or philosophical remedy to a spiritual illness. And a culture which pursues its own negation as its defining identity, seems uninterested in finding a cure.

Next: The conclusion to this series—looking at multiculturalism after Pierre Trudeau, and its current form today under his son, Justin Trudeau.

See Hebrews 10:16, 2 Corinthians 3:3, Romans 2:11-16.

English, John. Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Volume One: 1919-1968. (Knopf Canada; First Edition, 2006), 10.

English, Citizen of the World, 94-95.

English, Citizen of the World, 101.

English, Citizen of the World, 123-195.

English, Citizen of the World, 146.

Trudeau, Pierre Elliot, Hébert, Jacques, trans. I.M. Owen. Two Innocents in Red China. (Oxford University Press, 1968), 149.

Trudeau, Pierre. Against the Current: Selected Writings. (McClelland & Stewart, 1996), 27-28. Originally “Politique fonctionnelle,” Cité libre, June 1950, 20-24.

English, Citizen of the World, 283.

'No place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation', CBC Archives.

‘The Greatest Canadian’ series.

Torrance, Judy. Public Violence in Canada, 1867-1982. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988), 37.

FLQ Manifesto. ed. Bélanger, Damien-Claude. page 8.

Tetley, William. The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider's View. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2006), 103.

Trudeau, Pierre Elliot. “The New Treason of the Intellectuals” April, 1962. Cité libre.

Trudeau, Pierre Elliot, ed. Graham, Ron. The Essential Trudeau. (McClelland & Stewart, 1998), 16.

Trudeau, “The New Treason of the Intellectuals”.

Trudeau, The Essential Trudeau, 146.

Kelley, Ninette, Trebilcock, Michael. The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. (University of Toronto Press, 2010), 380-81.

Pageau, Matthieu. The Language of Creation: Cosmic Symbolism in Genesis: A Commentary. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, May 2018), 87.

Quoted in English, John. Just Watch Me: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Volume Two: 1968-2000. (Vintage Canada, 2010), 37.

English, Just Watch Me, 37-39.

Gregory of Nyssa: The Life of Moses. (Paulist Press, 2002), 94.